This viral game in China reinvents hide-and-seek for the digital age

On a late October evening, I found myself hiding in the shadows of a tree in a Hong Kong park. I was on high alert, warily eyeing everyone walking toward me. I was checking my phone every few seconds, watching the locations of dozens of people who were trying to hunt me down.

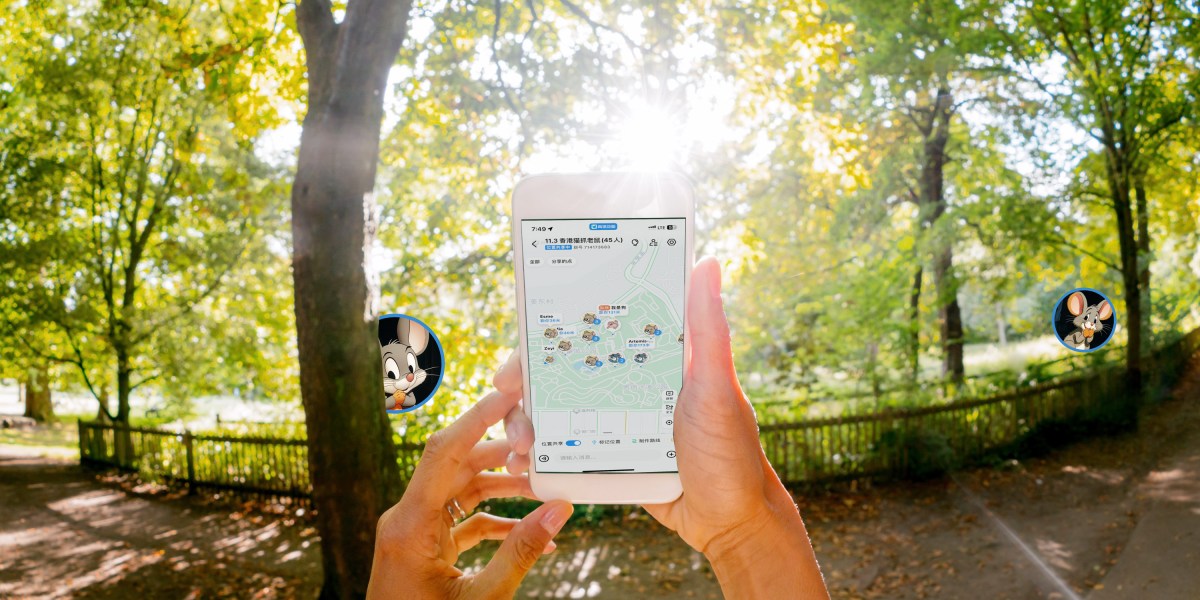

I wasn’t actually in danger. I was playing a game of hide-and-seek with 40 strangers in a seven-acre park built on the site of the infamous Kowloon Walled City. It wasn’t a typical hide-and-seek game, though, but rather one for the digital age: both the seekers and the hiders chase and evade each other by following their real-time locations on a map on their phones.

The “cat-and-mouse game,” as it’s usually referred to locally, has gone viral in China this year, drawing thousands of people across the country to events every week. It’s a fun combination of a childhood game, in-person networking, the latest location-sharing technology, and meme-worthy experience. When the game first emerged in February, videos of hide-and-seek players who went wild—climbing up trees, hiding in the sewers—got millions of views on social media.

Each contest convenes dozens of people in a predetermined area, often a large city park. All of them then join a group on Amap, a Chinese Google Maps alternative, and share their live location. Among the participants, 90% are designated as “mice” and have five minutes to run and hide. Then the rest, who are “cats,” will go out and hunt down each mouse with the help of the location sharing, as well as a neon wristband that visually separates them from nonparticipants. Once caught, the mice switch teams and join the cats, so the game gets harder and harder for the remaining mice.

@hypnus1127

During a short trip to Hong Kong last month, I joined two cat-and-mouse games in the city. Both of them had about 40 participants and lasted one hour. The first park was larger and had fewer people, meaning it was prime for running and chasing; the second was crowded and smaller, which made it ideal for trying to blend in with passersby.

Being an indoor person, I’m not always a fan of group physical activities, but the two experiences went far beyond my expectations. The addition of location sharing has turned the kids’ game into a more interactive version of Pokémon Go. Trying to remain hidden in the same spot throughout the game was not possible, since the cats could always see where I was; I needed to get more creative in crafting an escape plan. I quickly learned that deception—hiding my glowing bracelet, pretending to be an innocent jogger, and avoiding checking my phone too often—was also essential to being a good mouse.

Just watching everyone’s locations in the app was an intense experience. Dozens of little avatars were floating around in the park at once, with cats gradually outnumbering mice as the game progressed. Delays and bugs were plenty, but that added to the fun and difficulty of the game. I could feel safe at one moment, seeing there were no cats around, and panic seconds later when a cat suddenly moved hundreds of feet toward me, likely because its location sharing had lagged.

As a first-timer, I did okay. For my first game, I survived as a mouse until the last few minutes, when mostly everyone else had converted to the cat side. For my second outing, I converted mid-game and caught two mice myself.

I’ll readily admit some people were much better than I was. Hong Shizhe, a 19-year-old college student, was crowned the “cat king” of the second game, having caught 11 mice by the end. “I like that you can both exercise and have fun in this activity,” Hong says. He first learned about the game through videos people shared on Chinese social media, and he has been to several games in Hong Kong and mainland China since. He told me the largest one had more than 140 participants. Once, he even took his dog to the park with him and still won the game.

His secret for success? A lot of lies and politics: “You can make a deal with the mice and have them help you find other little mice. You can also pretend to be a mouse and strike up a chat with them.”

Half the fellow players Hong has met in his games are students, the other half young professionals. Like Ultimate Frisbee and a few other social activities that previously became popular in China, cat-and-mouse games are considered a great way for young people to meet each other and make new friends. At my two games in Hong Kong, I heard many participants chatting before the game started, many of whom were new to the city and eager to meet people.

But organizing the game has also become a business. Some games, like the second one I went to, charge participants a small fee (usually less than $10). That second game was hosted by a local group that organizes weekly activities, like camping trips, board games, and barbecue parties.

Transforming an ordinary map app

Many cat-and-mouse games use Amap, which is owned by Alibaba. Since Google services are blocked in China, and there aren’t as many Apple users, Amap is one of the most popular domestic map apps, with over 100 million active users every day.

Amap has enabled real-time location sharing within small groups since at least 2017, and it has in recent years expanded the maximum size of the group to 100 people. This feature has previously been advertised for users like family members tracking each other’s location or hikers keeping tabs on each other in the wild.

Perhaps inspired by the overwhelming success of Pokémon Go, Amap has done some experiments with gaming too. It has worked with a few Chinese game studios, as well as Alibaba’s e-commerce platforms, to develop games that integrate live location tracking, whether individually or in a group setting. None of these games, however, have caught on. The turn of events this year seems to have been more of an accident: cat-and-mouse was first played on WeChat, but players gradually moved on to Amap on their own and have basically made it the default app choice.

Amap declined to have anyone interviewed for this story, but the company is aware of its sudden popularity. Since September, the app has introduced a few features that cater to players’ needs. Now, users can specifically choose to start a “cat-and-mouse game group” right in the app and create groups over the typical 100-person limit; it can even randomly assign the roles of mice and cats. It also allows users to set customized rules and automates some of the formerly manual processes, like changing mice avatars to cats once players are caught.

All of these are nice-to-have features, but maybe not essential. At least for the two games that I went to, the organizers only used the most basic feature of group location sharing. Some didn’t even know the app had group features in the first place. (This may partly be because of where we were; Google Maps is much more popular in Hong Kong than other apps and only allows location sharing between two people.)

While it took a little time for the organizers to catch everyone up on how to use Amap and check that they had the right settings, the app is so easy to use that the whole group, including me, soon got the hang of it.

For a while, I was awed, reflecting that I never expected to be playing games in an app that guides people through their daily commutes. But soon enough, I had no time to think about that. A cat was approaching, and I needed to run for my life.