Turkey: from polarisation to pluralism

Could an Alevi social democrat defeat the authoritarian Erdoğan in next year’s election?

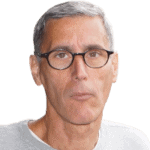

On September 5th Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, the leader of Turkey’s main opposition party, the social-democratic Republican People’s Party (CHP), announced his willingness to run as a presidential candidate in next year’s election—should the centrist electoral alliance of which the CHP is part agree.

Besides the social democrats, that opposition ‘Nation Alliance’ includes nationalists, conservatives, Islamists and liberals. The six parties to it have pledged to overhaul the current constitution, which gives unchecked powers to the president, restoring power to the parliament and securing the autonomy of the judiciary.

The polls show that Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, president since 2014, has lost ground and that the candidate of a unified, centrist opposition stands a realistic chance of winning. Erdoğan’s economic policies have impoverished the broad masses: consumer inflation exceeds 80 per cent and the number of poor increased by 3.2 million during the last two years, reaching ten million. While in 2012 per capita income exceeded $12,000, it has since fallen by a third.

The polls also suggest Erdoğan’s Islamic-conservative Justice and Development Party (AKP), which has been in power since 2002—ruling in alliance with the far right Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) since 2015—would lose the parliamentary election next year. The electoral system however gives an advantage to the biggest party and could ensure that the AKP remains the largest in parliament.

Our job is keeping you informed!

Subscribe to our free newsletter and stay up to date with the latest Social Europe content. We will never send you spam and you can unsubscribe anytime.

Inhospitable terrain

Historically, Turkey has been inhospitable terrain for the left. In a 2021 survey, two-thirds of the population identified themselves as conservative, nationalist and Islamist, only 13 per cent as social democrat and socialist. As a rule, the popular masses have rallied to populist conservatives who on the campaign trail have spoken to their religious feelings and resentment of the elite—while, in power, serving its economic interests.

Although the conservatives have held the reins of power for most of Turkey’s century-long existence, they have nonetheless succeeded in stigmatising the CHP as the party of an oppressive state. Above all, the CHP’s secularist tradition has created a gulf between its middle-class, progressive base and the popular masses. The right meanwhile has posed as the defender of traditional values.

Last year, Erdoğan pulled Turkey out of the Istanbul convention against gender-based violence, arguing that it harmed ‘family values’ and promoted LGBT+ rights. Kılıçdaroğlu has vowed to sign Turkey back up to the convention should he become president next year, as can be expected from a progressive. But the CHP leader is not alone. He is backed by Meral Akşener, leader of the right-wing nationalist Good Party, the second biggest in the centrist opposition alliance, which suggests that the conservative mindset in Turkey has evolved.

From Atatürk to reinvention

The CHP was founded in 1923, the same year as the Turkish republic. its founding leader and Turkey’s first president, Kemal Atatürk, carried out sweeping cultural changes which drastically limited the public visibility and role of Islam.

Initially, the CHP was an elite coalition of modernising bureaucrats and big landowners. Its authoritarian, one-party rule lasted until 1950, when it was defeated by the populist-conservative Democrat Party (DP) in the country’s first democratic election. The CHP subsequently reinvented itself as a democratic and eventually social-democratic party.

Kılıçdaroğlu, who has led the CHP since 2010, has sought to broaden its appeal by reaching out to religious conservatives. Since 1950, the CHP has emerged as the first party in only three elections (1961, 1973 and 1977) and has never gained a majority.

Kılıçdaroğlu has revived a tradition of left populism which, combined with an opening to religious conservatives, did pay off in the 1970s, the CHP’s high point. When it moved to the left, it succeeded in transcending the secular-pious divide and in winning over the working class and small peasantry. In 1976 the CHP officially declared itself of the democratic left and in 1977 its charismatic leader, Bülent Ecevit—who took inspiration from the Swedish social democrats—led the CHP to its best electoral score to date, 41 per cent.

Ecevit disagreed with those progressives who held that modernity and popular religiosity were in opposition and that the pious were by definition reactionaries. Calling this the ‘historical mistake’ of Turkish leftists, he set out to reconcile the left and the people, the seculars and religious conservatives. In 1974, Ecevit broke a taboo when he formed a short-lived coalition with the Islamist National Salvation Party (MSP). Ecevit is the only leftist to have served as head of government in Turkey.

We need your support

Social Europe is an independent publisher and we believe in freely available content. For this model to be sustainable, however, we depend on the solidarity of our readers. Become a Social Europe member for less than 5 Euro per month and help us produce more articles, podcasts and videos. Thank you very much for your support!

Past not reassuring

Like Ecevit before him, Kılıçdaroğlu aspires to change the widespread perception that the CHP has an issue with Islamic beliefs and he has vowed to ‘repair the damaged sense of unity within the society by reconciling people from all walks of life’. But Turkey’s past is not reassuring for the prospects of social democracy.

After his electoral success 1977, Ecevit formed a new coalition, but his government was undermined by the far right’s campaign of mass violence against the left. Ecevit lost power in 1979 and the CHP has been out of government since.

Unlike Ecevit, Kılıçdaroğlu has made a point of downplaying the left-right divide, claiming that ‘at this stage in Turkey, there is no right or left politics, there are those who are in favour of democracy and those who are in favour of the authoritarian regime’. Accordingly, in the municipal elections in 2019, Kılıçdaroğlu nominated a centre-right politician as the CHP’s candidate in Istanbul and a right-wing nationalist as the party’s candidate in the capital, Ankara. But even though he is wary of the leftist label, preferring the term social-democrat, Kılıçdaroğlu, as with Ecevit in the 1970s, nonetheless challenges the established capitalist order—and that has historically proved risky in Turkey.

The CHP leader has pledged to nationalise the assets of five conglomerates that have benefited from close ties to the Erdoğan regime, which he says ‘exploit’ the economy. But Kılıçdaroğlu is defying not only the crony-capitalist ‘order of theft’ but neoliberal capitalism itself. He recently declared that ‘savage capitalism’ and neoliberalism had wrought havoc on the planet and said he would join forces with activists and politicians around the world—such as the socialist American senator Bernie Sanders—dedicated to a more equitable distribution of wealth and incomes.

Moreover, the CHP leader is not a Sunni but an Alevi (Turkey’s heterodox Muslim minority) of Kurdish origin, who is thus anathema to the dogmas of right-wing Turkish nationalism. Indeed, the right-wing nationalists and conservatives in the opposition alliance are not comfortable with his potential candidacy. Ostensibly, Kılıçdaroğlu’s religious identity makes him unelectable. Yet, more than anything else, the sectarian opposition he faces is indicative of the inability of the nationalist right to come to terms with the religious and ethnic diversity of Turkey.

Kurdish questions

The CHP’s right-wing-nationalist allies are equally averse to accommodating the Kurdish minority. The political representatives of the Kurds—mayors and other elected figures—have been targets of massive repression since Erdoğan entered into an alliance with the far right in 2015.

Kılıçdaroğlu has vowed that Selahattin Demirtaş, the socialist former co-chair of the pro-Kurdish People’s Democracy Party (HDP), the third biggest in Turkey’s parliament—incarcerated since 2016—will be liberated. This puts him at odds not only with the Erdoğan regime but also with his nationalist allies.

When a leading CHP parliamentarian recently suggested that the HDP could be offered a place in a future government, this was strongly condemned by the leader of the right-wing-nationalist Good Party. Kılıçdaroğlu was forced to distance himself from the proposition.

Yet Kurdish support is crucial: the opposition will not prevail unless it successfully woos Kurdish voters. In the 2019 municipal election, it carried Istanbul, Turkey’s biggest metropolis, because Demirtaş had urged the Kurds to cast their votes for the CHP candidate. The CHP leader will thus need to convince the party’s right-wing-nationalist allies that steps have to be taken to end Turkey’s ethnic polarisation and accommodate the Kurds.

Kılıçdaroğlu has set out to ‘crown the republic with democracy’, but the social democrats will only succeed if the alliance with nationalists and conservatives holds, if the latter mobilise behind Kılıçdaroğlu’s candidacy. Ultimately, the prospects for democracy in Turkey depend on the nationalist right’s readiness to reconcile itself with the actual diversity of its imagined community.