Spilling Silicon Valley’s secrets, one tweet at a time

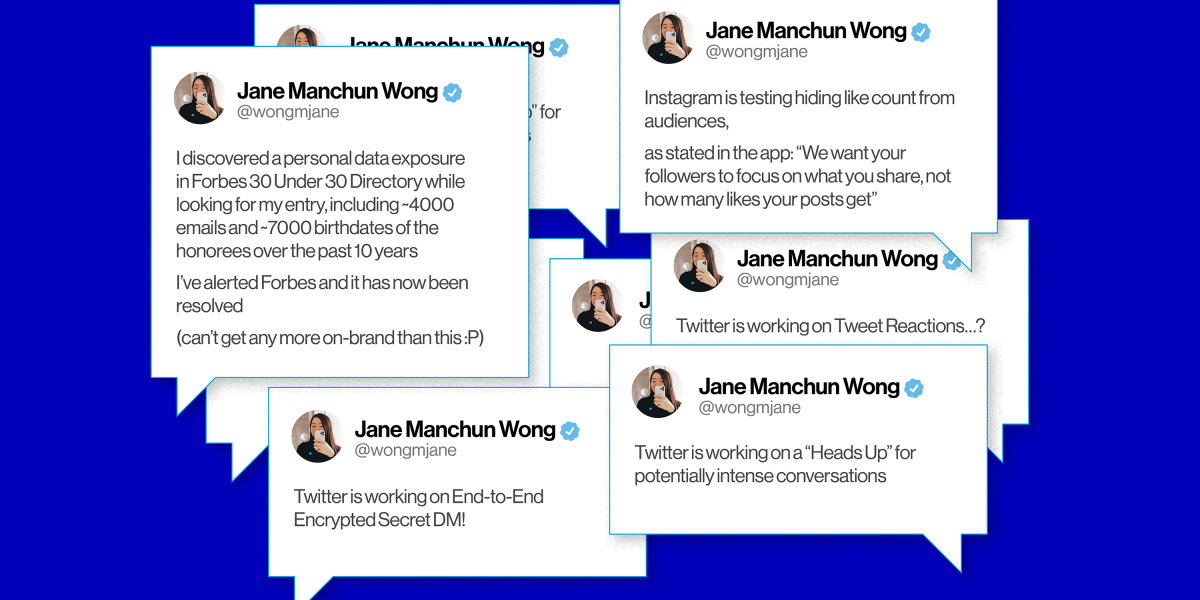

Shortly after midnight on May 4, 2018, Jane Manchun Wong tweeted her first “finding” ever. “Twitter is working on End-to-End Encrypted Secret DM!” she wrote.

A young woman of color, then just 23, exposing the plans of a Big Tech firm without any tools apart from her own ability to reverse-engineer code was (and is) pretty radical—and it’s changed the way tech companies work.

The tweet was the first of many that Wong would send out. By going into public source code for companies like Twitter, Facebook, and more, she has been able to find out what features and projects companies are secretly working on before they announce it. She takes the information she finds, tweets it out with a screenshot of the mocked-up feature, and watches the internet do its thing.

Wong, 27, has a preternatural ability to crack difficult code—along with a sizable Twitter following that includes some of the biggest names in tech and journalism. As she gets into the back end of websites’ code to see what software engineers are tinkering with, they await her discoveries with interest.

“Basically, there’s no such thing as a secret beta anymore for the world’s biggest apps,” says Casey Newton, the founder of the popular Substack tech publication Platformer. “If it’s in the code, Jane could find it. I do think that affects how companies think about testing new features and communicating about them.”

It isn’t Wong’s job to do this. In fact, she describes reverse-engineering code as her hobby. “I just like to dig deep into the apps and see how they are structured,” she says from her home in Hong Kong, where she lives with her family. She isn’t a hacker; all the data from which she derives her information is public. She’s more like the computer science version of Gossip Girl.

Wong’s Twitter feed is a near-daily scoop factory, but she insists that nothing she posts is a leak. “Leaks mean that they are based on information coming from employees, that employees are the source,” she says. “But I use publicly available data and code. They’re not leaks.”

Wong has built a reputation for always being right. Journalists cite her work in articles, crediting her scoops. “Initially, people would question, ‘Who is she? How does she have this information?’” she says. “But I built trust over time. You have to prove your information is valid.”

It’s gotten to the point where companies create Easter eggs for her to find. Newton says many have given up on trying to hide their code and simply play along. “There have even been cases where developers will put a ‘Hi, Jane’–style message in their code,” he says. “They know she’s coming.”

Wong’s work brings attention to the oft-ignored research and development parts of companies, which can be a PR win. Coders at Meta love her so much that they’ve created an internal Jane Manchun Wong fan club, which counts among its members Andrew Bosworth, the company’s CTO. “We value her contributions and feedback that help improve our products,” a Meta spokesperson says.

But even if they know she’s coming, that doesn’t mean they always welcome her. Showmanship and surprise are key elements of maintaining the aura that surrounds a tech launch or feature reveal—and Wong has blasted through these secrets, breaking tech companies’ carefully constructed walls. With one tweet, she effectively destroys any buildup or narrative they have about a feature.

This is precisely why, in fact, Wong says she tweets out features before they go public. To her, the secrecy and subsequent hype are problematic. Apps are used by people; shouldn’t those people know what updates and products are being worked on behind the scenes?

It’s not hard to imagine that companies might be disgruntled about a social media celebrity unceremoniously spilling their secrets on Twitter. And as a 20-something Asian woman posting a steady stream of bombshells about tech companies on Twitter, Wong is a prime target for the type of harassment and trolling that can break even the strongest of humans. “I wish more people realized I’m a person,” she says. “I’m more than a machine.”

It’s a contentious dynamic, and one that has affected her deeply. Several times over the years she has tweeted about being depressed and feeling that people hate her. She has been open about her mental-health struggles and says she continues to deal with depression.

And though Wong describes what she does as a hobby, at times it has been more of an obsession: she used to spend nearly 18 hours a day combing code and checking out what companies were tinkering with. She sacrificed her sleep and health, sometimes locking herself at home for days when the harassment became too much. A few times, she’s gone so far as to threaten suicide after being taunted online. She left the University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth, a few months short of graduating because of medical issues, something she regrets.

Is it all worth it? Wong believes it is, saying she’s noticed that companies are more transparent about what they are working on these days. “And if they had been before, I wouldn’t have to do this,” she says.

To support MIT Technology Review’s journalism, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Over the course of the pandemic, Wong has adjusted and reevaluated her schedule. She’s still a night owl, but she’s starting to find a balance. She’s taken up hiking the outskirts of the city, and she has found refuge at a local cafe nestled in a nearby church.

Quarantine has also made her realize that she doesn’t want to do this work full time. “I’ve been wanting to be a software engineer since I was six,” she says. “I want to create things.” But she’s not ready to get a job in tech, even though she’s gotten numerous offers. “I still haven’t gotten to the bottom of my curiosity for this,” she says. “When I satisfy that curiosity, I’ll stop. I’ll move on.”