Lebanon-Israel tensions rise, but life continues in disputed Ghajar

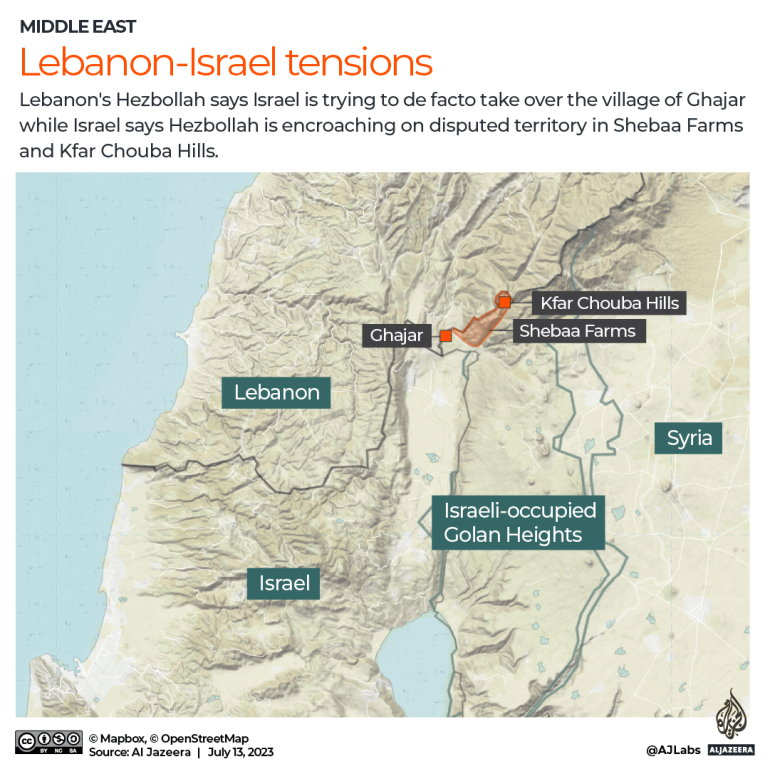

Kfar Chouba, Lebanon – From the hills of Kfar Chouba, a village in southern Lebanon that overlooks towns in the Israeli-occupied Syrian Golan Heights, the disputed village of Ghajar is fully visible.

Originally considered a part of Syria, Ghajar currently lies on a line of demarcation drawn by the United Nations between Lebanon and the Golan Heights, and has been occupied by Israel for most of the past 65 years.

Although Ghajar is split into two, its lush green landscape and ice-capped mountains extend as far as the eye can see, seemingly uninterrupted by the complicated geo-political history of the region.

Residents of Ghajar rush every morning to attend to their work, with many men employed by a growing number of factories and shops that dot the village.

With Israel eager to integrate occupied Ghajar into its economy, the town has seen a significant rise in the number of facilities producing food over the past few years, as well as shops selling everything from canned products to fresh zaatar, labneh, and olives.

These are “Syrian foods”, the villagers tell Al Jazeera by phone from across the border, explaining that their products are mostly sold in Israel because residents of Ghajar cannot cross into Lebanon or Syria, while Syrians and Lebanese cannot enter Ghajar.

Unlike the men, most women do not work in food production. Instead, they fill roles in Ghajar’s booming tourism industry, with new ski spots on Mount Hermon and trendy cafes and restaurants popping up across the town every year.

During the winter months, Ghajar’s mundane pace of life transforms as thousands of skiing and hiking enthusiasts from Israel and beyond visit the town to enjoy its scenic slopes and leafy trails.

Shops selling ski equipment stream with tourists as the town’s service sector peaks during the winter season, said Abu Nidal, a 68-year-old resident of Ghajar, who despite the prosperity of his hometown, felt disappointed and believed his people have been forgotten.

“What does it matter if we have these thriving businesses, but cannot connect with our neighbours in Lebanon and Syria,” he says.

Like the majority of the village’s 3,000 residents, the street vendor identified as Syrian but holds an Israeli passport.

“They [Lebanese and Syrians] are not able to visit us, nor are we able to visit them,” he adds.

Although Abu Nidal does not plan on giving up his Israeli citizenship, he said the town falls within Arab lands and should come under Syrian or Lebanese authority.

History of division

Along with the rest of the Syrian Golan Heights, Ghajar was captured by Israel in the 1967 Six-Day War. The village residents, most of whom belong to the minority Alawite community, have always considered themselves Syrian, according to Abu Nidal and residents of nearby Lebanese villages.

Abu Nidal recalled that after the 1967 war, some families in Ghajar decided to stay in the town, while others fled to Syria, and still others moved across the border and merged into Israeli society.

After Israel annexed the territory in 1981, the village’s population expanded into southern Lebanese territories which remained under Israeli control for another 18 years. During that time, most of Ghajar’s residents gained Israeli citizenship, said Abu Nidal.

When Israel withdrew from southern Lebanon in 2000, the village was split into Lebanese and Israeli sides demarcated along a temporary UN border known as the Blue Line.

With this division, neighbours that had lived across the street from one another for decades found themselves in two enemy states. Those in the northern part of Ghajar became unable to access schools and mosques they had always frequented in the south, and residents in the south became cut off from the north.

But during the 34-day war between Israel and the Lebanese Shia group Hezbollah in July 2006, Israel, again, took control of the Lebanese part of Ghajar. And despite Israel agreeing to withdraw from north Ghajar in line with the UN Security Council resolution that ended the fighting, Israel has not yet pulled out. Instead, within years, Israel started building a wall around the northern part of Ghajar.

UN peacekeeping forces (UNIFIL) have since called on Israel to end its building work in northern Ghajar and to withdraw its troops, but Israel has maintained de facto control over the village due to its strategic location in the vicinity of three countries – Lebanon, Syria, and Israel, said Lebanese military expert Antoine Mourad.

“After the truce, Israel withdrew from most of south Lebanon, except for an area it called ‘August 14’ [the day the 2006 war ended] – which includes Ghajar,” said Mourad.

Mourad said that Ghajar has been strategic for the Israeli army due to its proximity to Israeli settlements visible from southern Lebanon. “This status quo, although contentious, has been maintained for years,” he said.

But tensions returned to the region in early June as Israel filed a complaint with the UN over Hezbollah setting up two military-style tents – one inside the Blue Line on the outskirts of Kfar Chouba, and the other inside Lebanese territory.

Later that month, Israeli soldiers fired tear gas to disperse Lebanese protesters from southern towns after they pelted Israeli troops with stones. Hezbollah shot down an Israeli drone.

By early July, the situation boiled over with Israel shelling Kfar Chouba, saying it was in response to incoming anti-tank missiles fired from the town near Ghajar. The exchange has since threatened to re-ignite decades-long tensions between Hezbollah and Israel, with both sides threatening to send the other to the “stone age”.

‘Not recognised”

While tensions in the occupied West Bank this year have garnered the attention of the Arab world, Abu Nidal complained that both Israel and Arab states have forgotten about Ghajar.

“Israel treats us as second-class citizens because we’re Arab and the Arab world does not see us as their own,” he said, with sadness in his voice.

“Ghajar is, and always will be Arab, but I wonder if Lebanon or Syria can accept us back into their fold,” he adds.

According to 33-year-old Khaled al-Hajj, a resident of Kfar Chouba and a political history professor at the Lebanese University, Israel’s control over the village has manifested in “socially isolating” Ghajar from other villages in the south.

“Israel has successfully distinguished Ghajar from nearby villages,” al-Hajj said, explaining that Israel has done so by transforming the village into a tourist destination, developing its infrastructure, and integrating it into its agricultural and industrial sectors.

“Israel also built up its factories, roads, schools, and residential areas,” he added.

In comments given to Al Jazeera, Lebanese Foreign Minister Abdallah Bouhabib said that Ghajar’s complicated identity has been shaped by a strong Israeli state presence compared with a weak Lebanese one.

“Ghajar’s residents on both sides [of the Blue Line] hold Israeli citizenship and the village is surrounded by a military fence on all sides,” said Bouhabib.” The lack of a strong presence for the Lebanese state has only compounded this reality.”

Hezbollah’s tents

Despite international efforts to de-escalate the situation, Bouhabib said there has been little success.

Israel reinforced its forces along the border earlier this month as Israeli Defence Minister Yoav Gallant approved new operation plans in anticipation of a deterioration in the security situation with Hezbollah.

While Israel has claimed that its wall around Ghajar does not violate any agreements, Hezbollah has insisted otherwise and said it will not remove the tents until Israel withdraws behind the Blue Line.

“The tents are here to stay because they are outside of the Blue Line,” a high-ranking official in Hezbollah told Al Jazeera.

“Unless Ghajar returns to its former position before Israeli annexation [this year], Hezbollah is ready for an open military escalation, whatever the cost,” added the source who wished to remain anonymous for security reasons.

“Hezbollah will always have the final word [when it comes to Israel] and that’s why the presence of these tents is not only symbolic, but an essential part of our confrontation with the enemy,” he added.

As the escalation along Lebanon’s southern border with Israel continues, Abu Nidal said the tensions make life harder for Ghajar’s residents and do little to re-integrate them into the Arab region.

“We’re still living in limbo about where Ghajar fits into these regional divides, but we hope that one day, this injustice and the refusal [of Arab states] to recognise us will end,” said Abu Nidal.