Will Ukraine interior minister’s death cut reforms short?

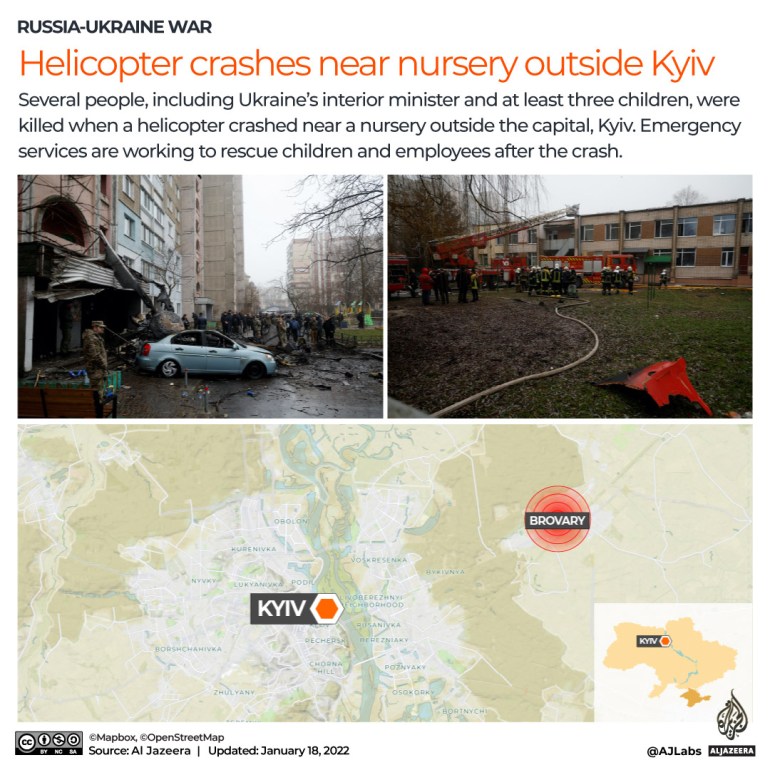

Kyiv, Ukraine – A helicopter crash has killed Denys Monastyrskyy, Ukraine’s interior minister, who was reforming his nation’s notoriously corrupt and brutal police force.

The 42-year-old lawyer was one of President Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s protégés appointed to clean up the Augeas stables of Ukrainian law enforcement.

Post-Soviet Ukraine’s interior ministry has about 350,000 staffers and an outsized role, which includes control over emergency and migration services as well as the border and national guard.

Tens of thousands of police officers have also been dispatched to work in the “anti-terrorist operation” against pro-Russian separatists in southeastern Ukraine since that uprising began in 2014.

Since Russia launched its invasion in February, Monastyrskyy had presided over the increased role of police in daily life.

His officers have cleared landmines in recaptured areas, exhumed the remains of civilians and collected evidence against Russian servicemen for war crimes prosecutions.

They have also built and operated “points of invincibility”, hundreds of tents where anyone could get warm, recharge their mobile phones and have a cup of tea or hot soup during Russian attacks on power stations that led to hours-long blackouts.

Rocked by scandals

For decades, the interior ministry’s top brass had political ambitions that often contradicted their job descriptions and led to dozens of scandals and a string of unsolved high-profile murders.

Monastyrskyy’s predecessor Arsen Avakov was appointed by previous President Petro Poroshenko. In 2014, he helped create dozens of volunteer battalions, including the Azov regiment, to fight the pro-Russian separatists and later made them part of the police force.

He faced criticism for backing far-right and ultra-nationalist groups that often assaulted their critics and brutally fought with police but almost always walked free without facing charges.

Avakov started widely publicised reforms that included obligatory exams and background checks for each police officer, which were aimed at eliminating corruption.

But critics said the reforms were superficial because most of the officers passed the exams. Meanwhile, the dismissed ones sued the interior ministry, and most got their jobs back along with hefty compensation.

After Avakov fell out with Zelenskyy and was fired in July 2021, Monastyrskyy took on a big job.

First, he succeeded in navigating his ministry away from political storms.

“Since his appointment, the ministry became a stable structure,” Igar Tyshkevich, a Kyiv-based analyst, told Al Jazeera. “It stepped aside from key political conflicts.”

At the time of Monastyrskyy’s appointment, the biggest question was whether the future minister would be able to lead his ministry himself or would just have to follow what the government wanted, Tyshkevich said.

“The interior ministry remained an independent centre of decision-making but, on the other hand, stayed away from political conflicts that were connected with personal ambitions of either former heads or some politicians that were somehow related to it,” Tyshkevych said.

To average Ukrainians, the reforms were palpable on the street level.

“At least they started communicating like normal people, not the way they used to,” Ihor Levchenko, a 23-year-old sales clerk in central Kyiv, told Al Jazeera.

He said that in the late 2000s, a friend had an altercation with a police officer who pushed him inside an apartment building away from potential witnesses and brutally beat him.

“They used to be like bulls, just did what they wanted, knew no limitations,” Levchenko said.

A ‘meticulous’ individual

Monastyrskyy is a native of the central Ukrainian city of Khmelnitsky, where he earned a law degree. He taught at a university and authored three legal textbooks.

But he rose to fame in the late 1990s as an amateur actor and part of a student comic trio named Three Fatsos.

A fellow amateur actor who performed with Monastyrskyy at community clubs, libraries and movie theatres recalled watching him get ready for a radio recital of Listen, a poem by Vladimir Mayakovsky that he liked.

“Of course, he knew it by heart, but he still worked on it very carefully with the director, rehearsing every line,” theatre critic Elvira Zagurska told Al Jazeera. “It seems to me that he was so meticulous in everything.”

At the time, Monastyrskyy met future president Zelenskyy, an actor who would found and lead District 95, Ukraine’s most popular comic troupe.

In 2007, Monastyrskyy joined the Hillmont Partners law firm, which worked with District 95.

Zelenskyy’s overwhelming popularity paved the way for his landslide victory in the 2019 presidential election, and Monastyrskyy soon joined his Public Servant Party.

He was elected to Ukraine’s parliament, the Verkhovna Rada, and worked on legal and police reforms.

In July last year, parliament approved his appointment as interior minister.

At the time, the police force had a broad array of problems – low salaries, long work hours and outdated equipment.

But from the start, Monastyrskyy said he wouldn’t antagonize his subordinates for the sake of rushed reforms.

“Knowing my background as a man from outside [the ministry] who understands the system deeply, they don’t expect rash decision,” he told the Interfax news agency three months after his appointment.

Monastyrskyy’s reform agenda

The reforms Monastyrskyy proposed included better accountability of each police officer to his own community, detailed surveillance of everything done to a detained person and improved security measures at public schools.

He also pioneered laws on the use of DNA during investigations and proposed a bill to create a database with the DNA of all Ukrainian soldiers to simplify identification in case of their death.

Slovo i Delo, an analytical centre that covers political reforms, said Monastyrskyy fulfilled 65 percent of his promises, an unusually high rating in comparison with other top officials.

These fulfilled pledges included better tools to investigate financial fraud, simplification of bureaucratic procedures for small businesses and financial incentives for Ukrainians who report corruption.

Monastyrskyy’s unfulfilled pledges included reworking anti-corruption government agencies, improving overtime pay for police officers, installing thousands of cameras to monitor traffic violations and establishing an electronic registry for gun owners.

The latter was his brainchild.

After the Russian invasion began in February, he advocated a loosening of gun restrictions, saying Ukrainians “can handle” tens of thousands of guns, including assault rifles, that have been distributed to civilians and militias.

As a result, public approval of the police rose.

Fifty-eight percent of Ukrainians “trust” police, according to a poll released last week by the Kyiv International Institute for Sociology. A year earlier, that figure was only 30 percent, it said.

However, some police officers didn’t accept Monastyrskyy and said his reforms were perfunctory.

“They have new uniforms, but the system remained the same,” a former police officer from Monastyrskyy’s hometown told Al Jazeera on the condition of anonymity. “All the old clans are still there, and the system will take generations to change.”