Why Africa does not appear to be ‘standing with Ukraine’

There have been many comments about Africans’ reactions to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the horrific violence it has unleashed on Ukrainians and the humanitarian catastrophe it has created.

Many people, including on this continent, have been aghast at what they see as the moral failure not just of African governments, but also of individual Africans, to outrightly condemn Russia for its clear and unwarranted aggression, as well as its imperial and colonial designs on another people’s land, with which they should be all too familiar.

Africans, including myself, who have pointed out the racist hypocrisies of Western media, governments and societies evident in the response have been accused of a convenient whataboutism which blinds us to the suffering of Ukrainians. Further, others have suggested that Africans are guilty of similar hypocrisies to those they accuse the West of, seemingly more concerned about events and crises thousands of miles away but happy to ignore the many crises on their own doorstep.

Much of this is true. At the UN General Assembly, African countries formed a significant proportion of countries either abstaining from or opposing a resolution to condemn the Russian actions.

On social media, one regularly encounters posts expressing explicit support for Russia, even though while reciting talking points such as NATO expansion and that the West has done similar things, most seem unable to articulate why that justifies the killing and maiming of thousands of civilians, the destruction of lives and livelihoods, and the displacement of millions.

And it is true that even as Africans point to the preferential treatment accorded to Ukrainians over migrants from less white parts of the world, there is much less talk about what African states themselves are doing to welcome refugees and the displaced from conflicts closer to home. You do not, as a rule, hear about private efforts by Africans such as myself to organise convoys to ferry Tigrayans to Kenya, or people taking Somali refugees into their own homes, as many across Europe are doing with regard to Ukrainians (though many will, I’m sure, point out that significantly fewer of these good white people were sending convoys or opening up homes when it was darker folks at the border).

Many Africans have also failed to see the commonalities between their struggles against imperialism and that of the Ukrainians, preferring to instead conflate the Ukrainians with their benefactors in Western Europe. Indeed, many, including myself, are almost entirely ignorant of the history of Russian colonialism in Eastern Europe and the fear it still inspires in the region. Worse, even today’s conflict, in which Ukrainians are trapped and dying in what increasingly looks like a proxy conflict between the West and Russia, of the sort Africans should be intimately familiar with, struggles to be recognised given that the victims are of a lighter hue than has been the case previously.

However, it is also true that many who rightfully criticise African responses themselves fail to recognise that African governments are making many of the same calculations that Western ones are. Just as the West is unwilling to sever its energy ties to Moscow for fear of what it means for their own economies and citizens, Africa will hedge its bets, especially countries in the eastern part of the continent like Kenya which gets up to 90 percent of its wheat imports from Russia and Ukraine.

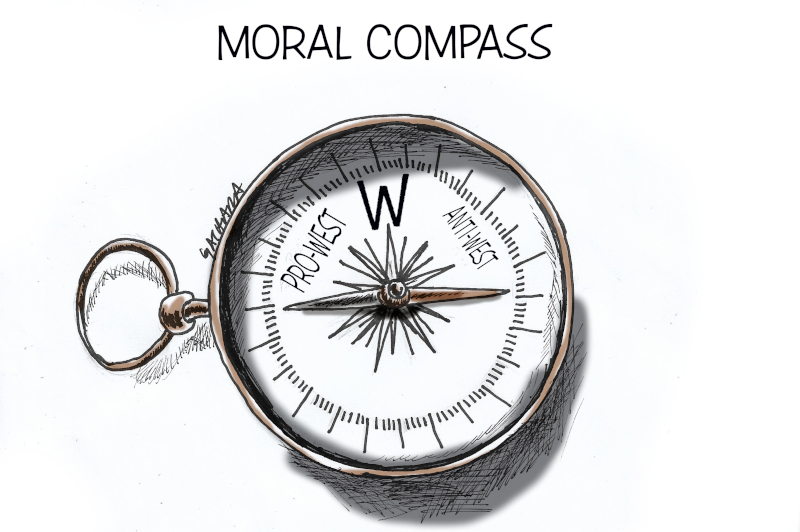

Further, they seem unable to recognise that what the world looks like to a large extent depends on where one is standing. And that many here are responding not so much to the invasion itself, but rather to Western reactions to it, which have rekindled long-running grievances that much of Africa has had with the West. The minimising of the Ukrainian state’s racism against African students trying to flee the conflict (with the Ukrainian ambassador to the UK even suggesting that Black people in Ukraine should be “less visible”), has rankled as has the hypocrisy in welcoming Ukrainian refugees while shutting out African and Middle Eastern ones. Ditto the gnashing of teeth over Ukrainian suffering and lionising their resistance, while pledging unconditional support to invaders like Israel and demonising the similar resistance of Palestinians, whom a UN rapporteur acknowledges are victims of an apartheid regime.

Sure, none of this justifies what Russia is doing, but it does sadly make standing with Ukraine, which the West is now presenting as a reflection of itself and its own values, rather less palatable. An example of this was the valorisation by the West of the Kenyan Ambassador’s speech at the UN Security Council at the launch of the invasion which, while correctly condemning it, used language that appeared to endorse the Western colonial project in Africa, as I argued here. Similarly, many may fear that standing with Ukraine could be conflated with standing with the West (as indeed many in Western media seem to think it is).

Delving a bit deeper, I think there is also a reaction in these parts to a perception that we in “underdeveloped” societies have been fed for a long time (since the days of the “civilising mission”) about the locations of dysfunction. It was a perception evident in the pearl-clutching reporting of Western journalists shocked that such senseless death and destruction could be visited on civilised Europe and the visceral reaction this provoked. Maybe, after centuries of being treated as the dregs of humanity, many are simply relieved that “Europe” (here again, there is much ignorant conflation of what European and whiteness are) is getting a taste of what they have wreaked elsewhere.

Finally, I think there is also a conflict between those who see the global attention and Western reactions to Ukraine as an opportunity to also talk about other issues, and those who say that with Ukraine fighting for its life, such whataboutism should be parked for another time. Yet does anyone think that once the fighting ends, the West will look more favourably upon the people in places like Gaza? Or on the plight of non-Ukrainian asylum-seekers in Europe? Or the racism faced by Black students, which did not begin with this conflict? If we cannot talk about the Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions (BDS) movement to end international support for Israel’s oppression of Palestinians at the time when the West is imposing wide-ranging sanctions on Russia for doing the same to Ukraine, when can we do it? Why shouldn’t countries at the General Assembly when pushed to stand with Ukraine ask: “What about Palestine?” There will be those who will say whataboutism costs Ukrainian lives by diluting international resolve. But doesn’t silence cost Palestinian lives?

From a human standpoint, I doubt that anyone would disagree that the Russian invasion is an unmitigated catastrophe. But “Stand With Ukraine” is not just a human statement. It is a political one, too. And so far, the political conversation, on both sides, appears to be winning out.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.