Who is the Wagner Group officer Putin asked to form ‘volunteer battalions’?

Kyiv, Ukraine – The lean, grey-haired man lying on the asphalt was so drunk he couldn’t utter his own name.

Ambulance workers found Andrei Troshev near a nine-storey apartment building in uptown St Petersburg, Russia’s second-largest city, on June 5, 2017, according to the independent Fontanka.ru news portal.

The inebriated Troshev had about $25,000 in cash, maps of Syria and purchase documents for tents intended for Russian forces fighting for Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s regime, Fontanka.ru reported, citing hospital records.

The 61-year-old, whose nom de guerre is “Sedoy” (“Grey-haired”), turned out to be one of the top officers of the Wagner mercenary group, which had formed a couple of years earlier.

“He is a typical character for Wagner,” Nikolay Mitrokhin of Germany’s Bremen University told Al Jazeera.

Just like many other staffers of the security wing of Concorde, Wagner chief Yevgeny Prigozhin’s multifaceted company, Troshev fought in the Soviet-Afghan war and later joined the police force in St Petersburg, Mitrokhin said.

On June 23, Troshev made a fateful decision – he refused to take part in Wagner’s aborted mutiny in Russia and was not in the private jet with Prigozhin and his top officers that crashed in western Russia on August 23.

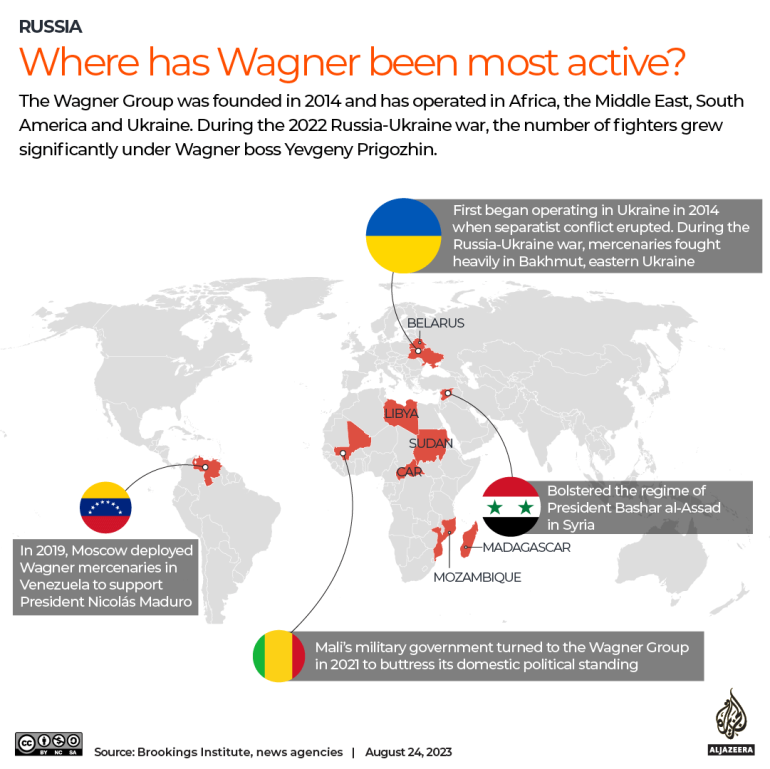

Since the mutiny, Wagner has left Ukraine and fractured, no longer playing a part in Moscow’s faltering war effort.

Some of its veterans have been lured to smaller private armies put together by state-run corporations or Kremlin-friendly oligarchs.

Some found a haven in Belarus, whose hardline president, Alexander Lukashenko, strengthened his law enforcement agencies in his power play with Russia.

And some are garrisoned in several African nations, whose leaders gave Wagner access to mineral riches and raw materials in exchange for security services.

The Kremlin did not want entire Wagner units back on the Ukrainian battlefields because they proved too unruly as Prigozhin engaged in widely publicised conflicts with Russia’s top brass, military analysts said.

“Whole Wagner Group units could lead to problems of Russian Ministry of Defence’s control as experienced under Prigozhin,” retired US army Major General Gordon Skip Davis Jr told Al Jazeera.

“Former Wagner veterans, however, could provide needed tactical expertise and small unit leadership to Russian formations,” he said.

These new formations will be helmed by Troshev even though he played a nefarious role in one of the bloodiest defeats Wagner has ever faced.

In February 2018, he and Prigozhin reportedly ordered an attack on an oil- and gasfield near the eastern Syrian town of Khasham without knowing that the area was controlled by US forces and the Syrian opposition.

Wagner suffered a humiliating defeat and heavy losses in what became the first post-Cold War armed clash of Russian and US nationals.

However, Troshev was awarded the Hero of Russia medal for his service in Syria.

Prigozhin’s mutiny began after the Defence Ministry said each Wagner fighter had to sign contracts to become part of the military machine known for corruption, ineffectiveness and miscalculations that proved lethal to thousands of Russian servicemen. Prigozhin ultimately refused to sign these contracts, increasing tensions.

And it is these contracts that are exactly what Troshev is after these days.

On Saturday, Troshev, clad in a bespoke dark-blue suit common among Russian officials, was filmed in the Kremlin heeding President Vladimir Putin.

Putin told him to “form volunteer battalions” that would include Wagner fighters.

“You know what it’s like, how it’s done. You know about the issues that need to be resolved in advance so that combat work goes on in the best and most successful way,” Putin said.

But the task is doomed because of Troshev’s reputation within Wagner, analysts said.

“The core of most battle-tested Wagnerites is not joining him for sure,” Kyiv-based analyst Maria Kucherenko, who authored several in-depth reports on Wagner, told Al Jazeera.

Troshev also faces a new rival.

Prigozhin’s son and heir, Pavel, is “making a deal with the Russian national guard so that Wagner returns to Ukraine for a certain task without signing a contract,” Kucherenko said.

Wagner mercenaries will also fight “under their own insignia” of a human skull against a black and red backdrop, she added.

However, it’s crystal clear who would control these mercenary groups.

“One can shuffle these alcoholic pensioners, one can make up a dozen noms de guerre, but the essence doesn’t change – both kinds of crap are controlled from [Russia’s] general staff of armed forces,” she said.

Meanwhile, the Kremlin is pressuring the Wagner fighters in Africa who are reluctant to sign up for service in Ukraine by “deliberately blocking supply chains”, Mitrokhin said.

As a result, a Telegram channel with ties to the Russian military and Wagner claimed that “three stormtrooper squads” flew from Africa to Ukraine last week.

The deployment followed a deal between their commanders and Russia’s national guard to sign individual and group contracts, the Russian pro-war Telegram channel Rybar claimed.

It’s not clear where the units are going, but their arrival will “contribute to the fall-winter campaign”, it said.

So far, Ukrainian intelligence reported the return of about 500 Wagner fighters to the front lines and said their presence is not expected to crucially change the deadlock.

At Wagner’s height in June, Prigozhin bragged he had 25,000 fighters, who were largely recruited from prisons, Davis said.

They played a key role in capturing the eastern Ukrainian town of Bakhmut “at great cost in casualties”, he said.

Therefore, “some 500 men are not likely to make any significant impact, especially if dispersed among various Russian units”, Davis concluded.