What draws the gold mafia to ‘Dubai, Dubai, Dubai’?

Over the last 20 years, Dubai has become one of the biggest gold-trading hubs in the world. The United Arab Emirates (UAE) is the world’s second-biggest importer of gold by volume, behind only India.

Yet, while Dubai’s markets draw millions of tourists from around the world, the city has also emerged as a preferred destination for money launderers and gold smugglers trying to wash their dirty cash, according to the United Nations (PDF), think tanks and non-profits tracking illicit trade.

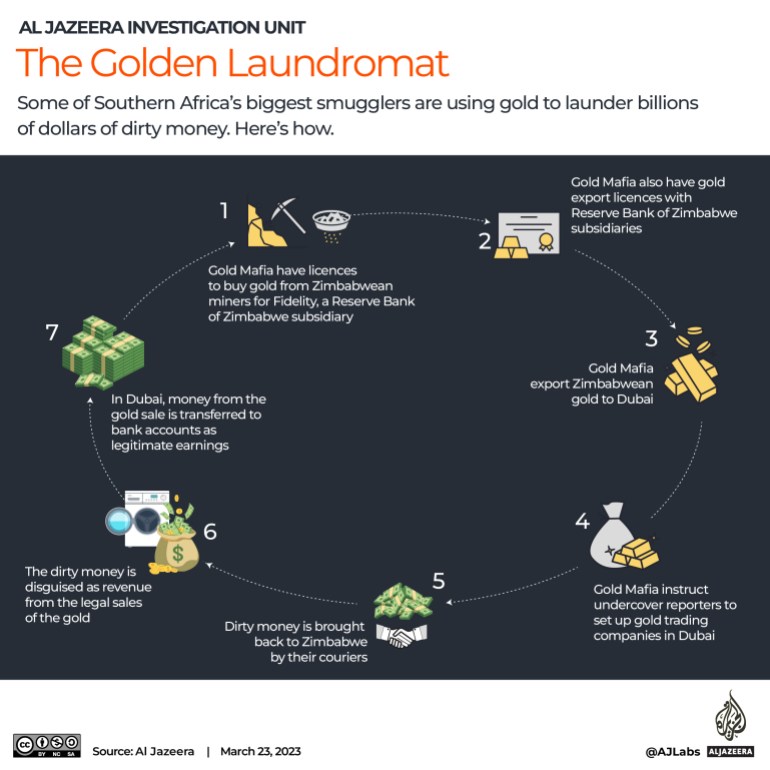

Gold Mafia – a four-part Al Jazeera investigation into major Southern African smuggling gangs – uncovers the process that allows these groups to abuse Dubai policies, designed to facilitate business, to instead cleanse billions of dollars of tainted gold and cash.

“It all comes out of Dubai. Dubai, Dubai, Dubai,” Zimbabwean gold smuggler Ewan Macmillan told undercover reporters from Al Jazeera’s Investigative Unit (I-Unit).

‘They don’t bother’

For years, Dubai has ranked near, or at the top of, cities globally that attract the most foreign direct investment. It is also a popular commodities trading hub. That reputation has been built on the back of a series of policies to attract businesses.

Dubai’s so-called free zones – trade areas specifically established for foreign investors to easily set up their companies – are at the heart of this strategy, with no taxes and duties, negligible bureaucratic red tape and norms that allow quick repatriation of profits.

But critics say those same policies also enable large financial crimes to slip through the cracks.

“Dubai was set up to be a financial capital,” former United States Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) investigator Karen Greenaway, who now works as an anti-money laundering consultant, told Al Jazeera. “They have set themselves up to be in the middle of the gold trade, with lax laws and no enforcement.”

“All of those things make Dubai a great place to have something like this, a major international money laundering operation involving, in this case, gold smuggling,” she said, referring to the Al Jazeera investigation.

The absence of “policing” of the free zones allows them to be abused, Greenaway said.

During the Gold Mafia investigation, Kamlesh Pattni, a gold smuggler who was once accused of nearly bankrupting Kenya, took undercover reporters – who he believed to be Chinese criminals – to Jumeirah Lake Towers (JLT), one of Dubai’s free zones.

Pattni has multiple companies in Dubai. At one of his offices in JLT, he told the reporters they could park gold bought from their unaccounted cash. “You need a representative office in the Gold Tower,” Pattni told the reporters, referring to a skyscraper in the JLT district that houses several gold firms.

Another smuggler, Alistair Mathias, also advised the reporters to set up a company with an office in Dubai’s free zones, and offered to help them with the process. “Whatever is grey area, I take to Dubai,” Mathias, a business partner of fellow smuggler Ewan Macmillan, said.

Asked if authorities in Dubai might scrutinise the company he had asked the Al Jazeera team to set up, Mathias said: “They don’t bother.”

‘Practically brand new gold’

According to research by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in 2020, the so-called hawala system plays a significant role in the money laundering chain that passes through Dubai.

Hawala is a way of transferring cash across borders outside the scrutiny of the formal financial system. It relies on trust and connections, and is used often for legitimate reasons in regions where people do not have access to banks. But it is also ideal for money laundering as there are no official transactions on the books, making it impossible for authorities to trace money flows.

“A combination of loosely regulated gold imports, poor oversight of free trade zones, trade misinvoicing, and the flow of currency via informal systems like hawala are a boon to trade-based money laundering networks,” the Carnegie report on Dubai’s gold trade said.

During Al Jazeera’s investigation, smugglers like Pattni and Macmillan offered to use Zimbabwean gold to effectively turn dirty cash into legitimate money for our reporters.

The gold from Zimbabwe is sent to a Dubai refinery where it is melted down again. It is then turned into a gold bar with the Dubai refinery’s stamp. Evidence of its roots is eliminated, making it easier to sell the gold because of the taint associated with Zimbabwe and its leaders as a result of Western sanctions.

“Gold that comes to refiners, once it’s refined, it’s practically brand new gold,” said Amjad Rihan, a former partner at global accounting firm Ernst & Young whose work involved tracking the gold trade in Dubai. The money from the sale of this gold is then transferred into bank accounts as legitimate earnings.

‘Very disturbing findings’

In 2013, while working at Ernst and Young, Rihan was tasked with auditing Kaloti, which was Dubai’s largest gold refinery at the time.

“They were very disturbing findings. We found that Kaloti was doing over $5.2bn in cash in one year,” Rihan told Al Jazeera, explaining that dealing in cash makes risk assessment and customer due diligence a lot more difficult. “That represents about 40 percent of Kaloti’s business done in cash.”

On top of that, Kaloti was dealing with sanctioned countries or entities, including conflict gold from Sudan, he said. Subsequent investigations connected these trades to money-laundering and financing organised crime.

“We concluded that Kaloti’s due diligence management system was a huge failure,” Rihan said.

Rihan reported his findings to his superiors but was forced out of the company for blowing the whistle, a court in the United Kingdom ruled in 2020. The court found that Ernst & Young had tried to “sweep under the rug the findings” of Kaloti’s “money laundering”. Rihan’s experience was not unique.

As head of compliance at Deutsche Bank in Dubai, Anna Waterhouse’s role was to ensure transactions complied with both local and international laws and regulations. She too noticed irregularities with Kaloti’s business.

She filed what is called a suspicious activity report (SAR), which noted irregular behaviour by the bank’s client, Kaloti. In it, she cited reports from a local Dubai bank that Kaloti was withdrawing so much cash from their accounts that they needed to use wheelbarrows.

“To have a bank calling because they were concerned about their own client is very, very unusual. So, straight away that was a red flag to me.” The cash withdrawals were largely funded by transfers from Kaloti’s Deutsche Bank account.

The SAR is a first step to ensuring a bank’s client engaged in questionable behaviour is subject to further scrutiny. Deutsche Bank, however, saw that differently, Waterhouse said. “When I said that I was going to and we should all file suspicious activity reports, I was met with resistance.”

A later audit of Deutsche Bank’s business with Kaloti revealed that the bank’s automated transaction monitoring systems also flagged a number of transactions over the years. “None of those instances picked up by the system had actually been manually investigated, so far as I could work out,” Waterhouse said.

In 2015, the Dubai Multi Commodities Centre (DMCC), the city’s main licensing authority for commodities trade, acted against Kaloti, removing the company from Dubai’s list of approved gold refiners.

The DMCC told Al Jazeera that it is not a regulator but provides companies the necessary licenses to operate within the Dubai Free Zone using a “clear, comprehensive and robust compliance process”. It also emphasised that it was not given an opportunity to provide evidence or make representations during the court action in London between Amjad Rihan and EY. It denied allegations made against it in those proceedings, and strenuously denied being involved in money laundering or criminal activity of any kind

Kamlesh Pattni denied involvement in any form of money or gold laundering and that he had offered to deal with funds he knew originated from illegal sources. He told us that, when he met with our undercover team, he believed he was meeting with an investor who wanted to buy a stake in hotel businesses and “to divest of a portfolio in China into gold buying and mining” and that all he did was to help them understand the gold business.

Alistair Mathias denied that he designed mechanisms to launder money and said he had never laundered money or gold, or traded illegal gold or offered to do such things. He told us he had never had any working relationship with Ewan Macmillan.

Ernst & Young said that it was the work of its staff that identified and reported irregularities, resulting in sanctions and changes to the sourcing of precious metals and the regulation of refiners in Dubai.

Kaloti denied all wrongdoing. It said that substantial transactions in cash were “perfectly legal and common” in Dubai at the time in question and did not amount to evidence of criminality or wrongdoing.

Others mentioned in this report did not respond to our request for comment.