Warning of ecological disaster over Malaysia forest plantations

Kelantan, Malaysia – When Sia Beng Hok goes to check his rubber and batai (Moluccan albizia) trees, he makes sure he has a rifle on the backseat of his four-wheel drive.

His plantations – all 5,000 hectares (12,355 acres) of them – sit on forest reserve land in Kelantan state, in the northeast of the Malaysian peninsula – and the rifle is vital to kill or scare away wild animals.

“There are all sorts of them. Wild boars, snakes, panthers, elephants,” Sia said. But for the larger plots, he resorts to other measures, running electric fences up to 10 kilometres (six miles) long to keep out elephants that might otherwise destroy his rubber trees.

Sia, wiry and tanned from more than 30 years in the logging industry, began planting trees for timber in 2008. He speaks of his work with pride, calling it “ecological” because his workers cut and replant the trees in cycles.

“If forest plantations are successful, it will replace the timber [logged] from natural forests. This is a great help to our country’s economy,” said Sia, who ended his term as the president of the Kelantan Forest Plantation Association in February.

Sia’s plantations are the result of a policy by Malaysia’s federal and state governments to develop forest plantations and create a sustainable source of timber for the domestic wood industry, which rakes in as much as 25 billion Malaysian ringgit ($5.7bn) in export revenue every year.

But in one of the most biodiverse countries in the world, critics say it has been an ecological disaster.

“Forest plantations, particularly those cultivated with exotic species, will result in homogeneous or simplified habitats that can only support a limited number of fauna and flora species,” Badrul Azhar, a forest ecologist at Universiti Putra Malaysia, told Al Jazeera.

“Rare, threatened, and endangered species are almost certainly absent from forest plantations.”

Between 2007 and 2021, the federal government loaned planters some 1.05 billion ringgit ($238m) while state governments, which have control over land, granted forestry companies concessions lasting as long as 66 years.

Consequently, about 6.1 percent of forest reserves in the peninsula were licensed to be cleared for forest plantations, mainly rubber, which is popular with furniture manufacturers but also other non-native species such as acacia and eucalyptus.

The ecological effect of the forest clearance is already being felt, even though the plantations themselves have yet to deliver any substantial economic benefits.

Felling for monocultures

Much of the logging in Malaysian forest reserves since the 1980s has been selective – loggers cut only a limited number of large trees. But operators of forest plantations take a starkly different approach – removing every tree so they can replant the entire site with a single tree species.

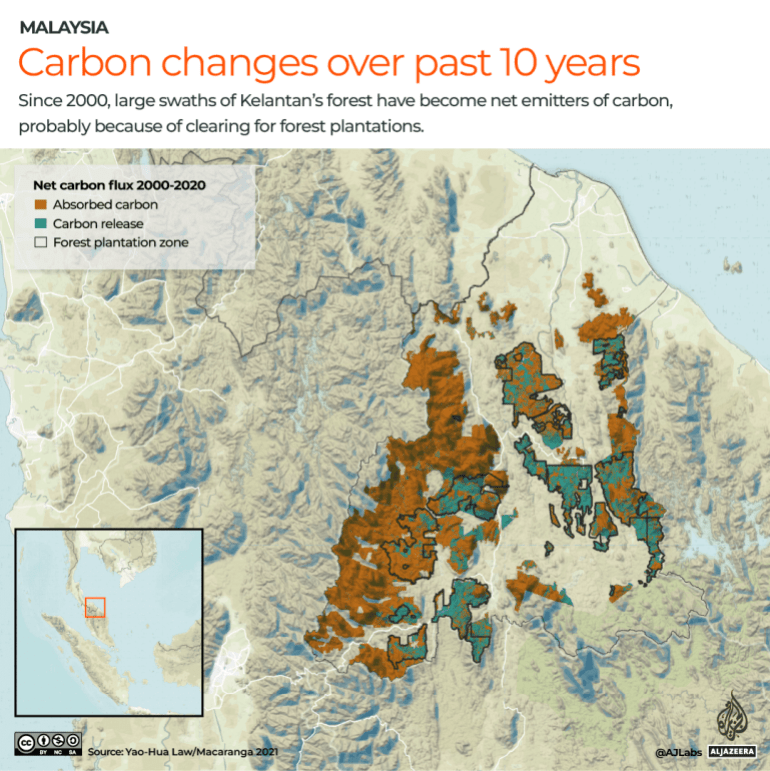

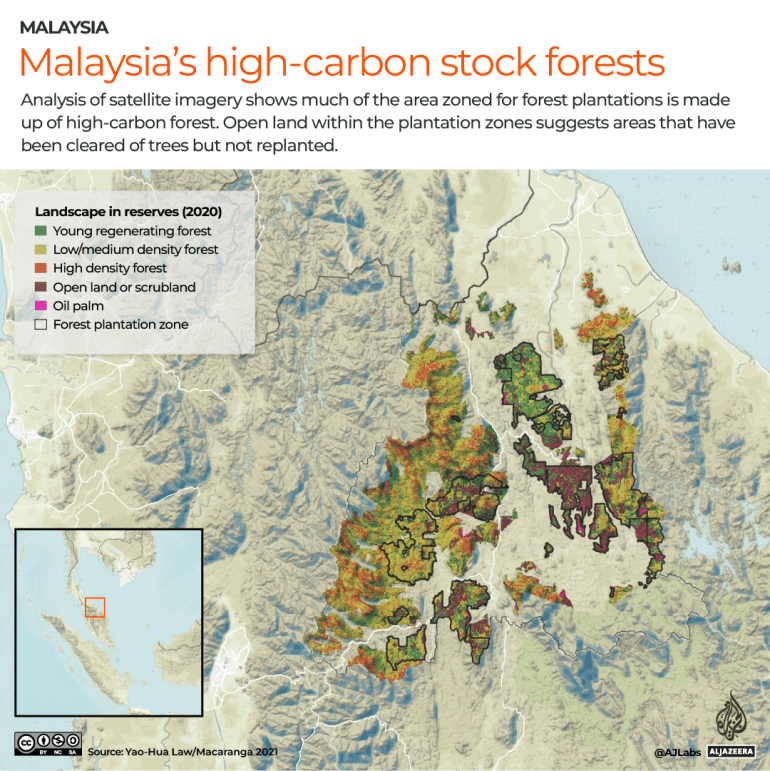

The cost is most evident in Kelantan. The state government there has zoned some 199,000 hectares (xxx acres) or almost one-third of its reserves, for forest plantations. Much of these reserves are high carbon stock forests.

Clearing these zones for forest plantations has coincided with significant carbon emissions over the last 20 years, as indicated by analyses of greenhouse gas inventories and tree loss.

And the forest removal is hampering Malaysia’s commitment to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 45 percent by 2030 under the Paris Agreement.

Replacing natural forests with plantations also jeopardises Malaysia’s commitment to the Convention on Biological Diversity.

The country’s natural forests harbour hundreds of species of plants, birds, and mammals, including elephants and tigers. The critically endangered Malayan tiger is estimated to number fewer than 150 in the wild, but in Kelantan many tiger habitats identified in 2005 have now been re-zoned as forest plantations.

Monoculture forest plantations might affect biodiversity similarly to oil palm plantations, said forest ecologist Badrul. Studies in Malaysia have found that monoculture plantations are “biodiversity-impoverished habitats”, and such homogenous habitats “would be unlikely to support the majority of forest-dependent species across all animal and plant taxa,” said Badrul.

Forest plantations are being established almost entirely in what are known as forest reserves.

These reserves make up 85 percent of all forests in the peninsula, and they are managed according to the National Forestry Policy mainly to safeguard timber supply. As such, about 60-70 percent of reserves in the peninsula are earmarked for timber production and can be logged, albeit mostly selectively. The rest are protected for their ecological services or for research and cannot be logged.

Forest plantations have encountered financial, technical, and policy problems.

Unexpectedly tough planting and market conditions have stumped planters and neither they nor government officials can guarantee the timing of harvests or what can be planted.

In March and April, the state governments of Kelantan and Pahang announced that they had cancelled about 35,000 hectares (135 square miles) of forest plantation projects where natural forests had been cleared but the concession holders had failed to replant. The two states have approved the most forest plantation in the peninsula.

Foresters at the federal and state levels say that devastation is only a temporary part of the process.

Zahari Ibrahim, the deputy director-general of the Forestry Department Peninsular Malaysia, said that while a forest plantation would look “quite like a disaster” during site-clearing, “after you plant and manage, it will become a nice forest.” Zahari headed the Kelantan state forestry department for five years until 2019.

He added that because forest plantations could be depended on to produce timber more regularly than natural forests, governments like Kelantan’s were “smart to plan early” for them.

The Kelantan chief minister did not respond to questions from Al Jazeera. But during a eucalyptus plantation site visit in 2020, his deputy said that forest plantations could reduce logging in natural forests, generate state revenue, and provide much-needed timber for the furniture industry.

Plantations not established

Federal government agencies have modelled forest plantations on a 15-year rotation, and the first timber harvest was expected by 2022.

So far, this year little timber – perhaps none – has reached the mills.

Planters have refused to fell their rubber trees, preferring to tap them for the more lucrative latex instead.

In Malaysia, rubber wood is one of the cheapest sources of timber on the market. Prices remain low despite solid demand because a government export cap means there is ample local supply.

In contrast, latex fetches good prices and offers planters a steady cash stream. It would be a waste to fell a rubber tree for timber and forsake the latex, said Sia, and government officials cannot force planters to cut.

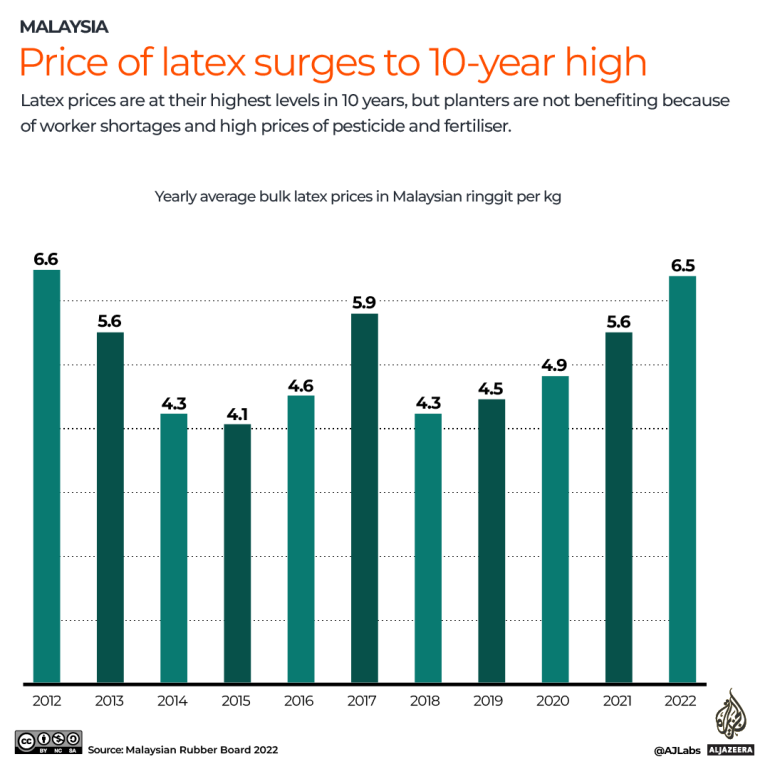

But even as latex prices climb to heights not seen since 2012, planters are reaping little of the windfall.

Most of the migrant workers – the majority Indonesian – who worked on the plantations left Malaysia during the prolonged pandemic lockdown, and new workers have been slow to arrive as Malaysia and Indonesia negotiate a new labour agreement.

Sia and many of his peers are having to get by with only 10 percent of the workforce they need, frustrated at the uncollected latex and weedy fields.

Meanwhile, the cost of pesticides and fertilisers has also doubled, so planters spray the minimum necessary to protect their plantations from termites and diseases. One planter called the situation a “noose around our necks now”.

Er Ka Wei is the managing director of Acacia Industries. The company started growing rubber forest plantations in 2006 and now has 8,800 hectares (34 square miles) in Kelantan. He and his timber-trading partners believed growing rubberwood would be a profitable business. Fifteen years later, he warns otherwise.

“I won’t consider [getting into] this industry altogether [now],” he said. “I tell you honestly. No way.”

While Sia and Er have planted trees, many others have not, leading to criticism that the projects were simply an excuse to clear-fell forests.

Between 2012 and 2020, only one-third of the reserves licensed to be cleared for forest plantations was replanted, according to an analysis of data in the forestry department’s annual reports. The majority of the remaining two-thirds was almost certainly removed and then left as is.

Abdul Khalim Abu Samah, who has been Kelantan state forestry director since 2020, admits that forest plantations had been used as an excuse by the unscrupulous to clear-fell reserves.

When the forest plantation development programmes began, there were no proven procedures to filter the applicants. “[In the past] when we got loggers, they didn’t plant, they cut and ran,” said Abdul Khalim. He has been imposing stricter conditions for new planters and cancelling dormant plantations but is due to retire this month.

Planters would try to replant after logging, say Sia and Er, if only to recoup their ‘plantation deposits’ (3,000 Malaysian ringgit per hectare) in Kelantan from the government. The deposit is a pre-requisite for plantation licences, and is refunded if the planters carry out their contracts with the government. But some planters forfeited the deposits because they could not bear the capital and logistics demands of replanting. For others, the deposits are simply a price to pay to clear and harvest a dense natural forest.

For those planters who stick to their contracts and replant, they are prepared to fork out much more than the gains from logging the original forest.

It takes between one and two million Malaysian ringgit ($227,265 – $454,530) to set up a 400-hectare (988 acre) plantation, according to Corinna Cheah, who manages several forest plantations in Kelantan.

She rattles off a list of expenses: roads, drains, retention ponds, nurseries, workers, managers … maintaining the site would add another few million, she says. “Not everyone can afford it,” she said. “Very few people are disciplined enough to reinvest their logging profits into plantations.”

Pressure on moratorium

The planters interviewed for this story tried to distance themselves from those who had failed to replant.

“We cannot stop others from doing that,” Cheah said. “Logging without planting is quite common, I can only say that that is their decision. It’s inevitable.”

For some time, the Forestry Department Peninsular Malaysia, which is under the federal government, has been aware of the increasing expanse of unplanted forest plantations, says Deputy Director-General Zahari.

His office saw a need to rein in the expansion and advised the government to propose a moratorium.

In December 2021, the National Land Council, which includes the prime minister and chief ministers of the states on the peninsula, announced a 15-year moratorium on new forest plantations.

But the freeze, which is not legally binding, could falter.

Already, the government has set aside 500 million ringgit ($114 million) for entrepreneurs who want to invest in forest plantations across the country in 2021-2025, and state governments continue to laud the contribution of forest plantations to the economy.

With global economic conditions getting rougher, state governments, which own the land, are likely to find it harder to turn away the income from clearing forests for plantations.

Badrul, the forest ecologist, suggests an alternative: establish forest plantations outside of natural forests.

“To safeguard forest biodiversity, further clearing of natural forests, whether virgin or logged-over, should be halted or reconsidered,” he told Al Jazeera.

This story was produced with the support of the Rainforest Investigations Network for Yao-Hua Law and Macaranga, which published a four-part series on the sustainability of forest plantations in Malaysia.