Turkiye jails teen who added moustache to Erdogan poster

CAIRO: When the Sudanese Armed Forces and the Rapid Support Forces transformed the streets of Sudan’s capital Khartoum into a war zone, 48-year-old math teacher Muna Ageeb Yagoub Nishan and her children were forced to flee.

Before embarking on their long and perilous journey to Egypt, Nishan, her 21-year-old daughter Marita, 22-year-old son George, and 16-year-old son Christian hid in their home in Khartoum’s Manshi district, as battles raged in the street outside.

Free of consequences and accountability amid the lawlessness since the conflict began on April 15, the armed men roaming their neighborhood pose a threat to the civilian population, particularly women and girls.

“They want to traumatize us,” Nishan told Arab News from the safety of an apartment in Egypt. “Now the RSF are raping women. People think I am still in Sudan and are sending me digital pamphlets on what to do if I get raped so that I won’t get pregnant.”

According to Hala Al-Karib, a Sudanese women’s rights activist and regional director of the Strategic Initiative for Women in the Horn of Africa, gender-based violence, including rape as a weapon of war, is being perpetrated by members of the paramilitary RSF.

“That doesn’t mean that Sudan’s armed forces don’t have a track record of sexual violence, but present victims of violence and rape are all stating that RSF soldiers have committed such crimes,” Al-Karib told Arab News.

Before they fled, Nishan and her children were like many Sudanese — trapped inside their homes, fearing for their lives. As the fighting raged, they quickly ran out of food and were forced to survive on rationed water until they found their opportunity to escape Khartoum.

When the RSF came knocking, Nishan’s 26-year-old son, Nadir Elia Sabag, answered the door while the family escaped through the back. Sabag was supposed to reunite with the family, but, according to Nishan, he is still in Khartoum, his exact whereabouts unknown.

When the family caught the bus that would take them to Egypt, Nishan says it was attacked by prisoners recently released by the RSF from Al-Huda prison in West Khartoum’s Omdurman, with one passenger robbed at knifepoint.

Eventually, the bus was allowed to continue, and, after several days, Nishan and her children arrived in Cairo. “I have lost everything,” said Nishan. “l sold my house to pay for my husband’s cancer treatment in Egypt.”

FASTFACTS

Sudanese women’s rights activists accuse armed combatants of using rape as a weapon of war.

RSF’s predecessor, the Janjaweed, implicated in similar crimes during the 2003-20 Darfur conflict.

Nishan had returned to Sudan only two years ago following the death of her husband. Now, all that she had rebuilt since then has been lost. “I have lost my car, my gold, my documents,” she said. “I lost everything with this war.”

Nishan and her children arrived in Cairo 10 days after Sudan’s descent into chaos. Today, they live in an apartment with other Sudanese families in the city’s El-Khalifa El-Mamoun district, awaiting an appointment with the UN refugee agency, UNHCR — scheduled for October.

“We don’t know what we will do next month, where we will go and what we will do for work,” Nishan said. “We hope we can make it to Europe.”

Her story is not unique. It is shared by thousands of other refugees who have arrived in Egypt in recent weeks, now the primary destination for people fleeing the conflict in Sudan.

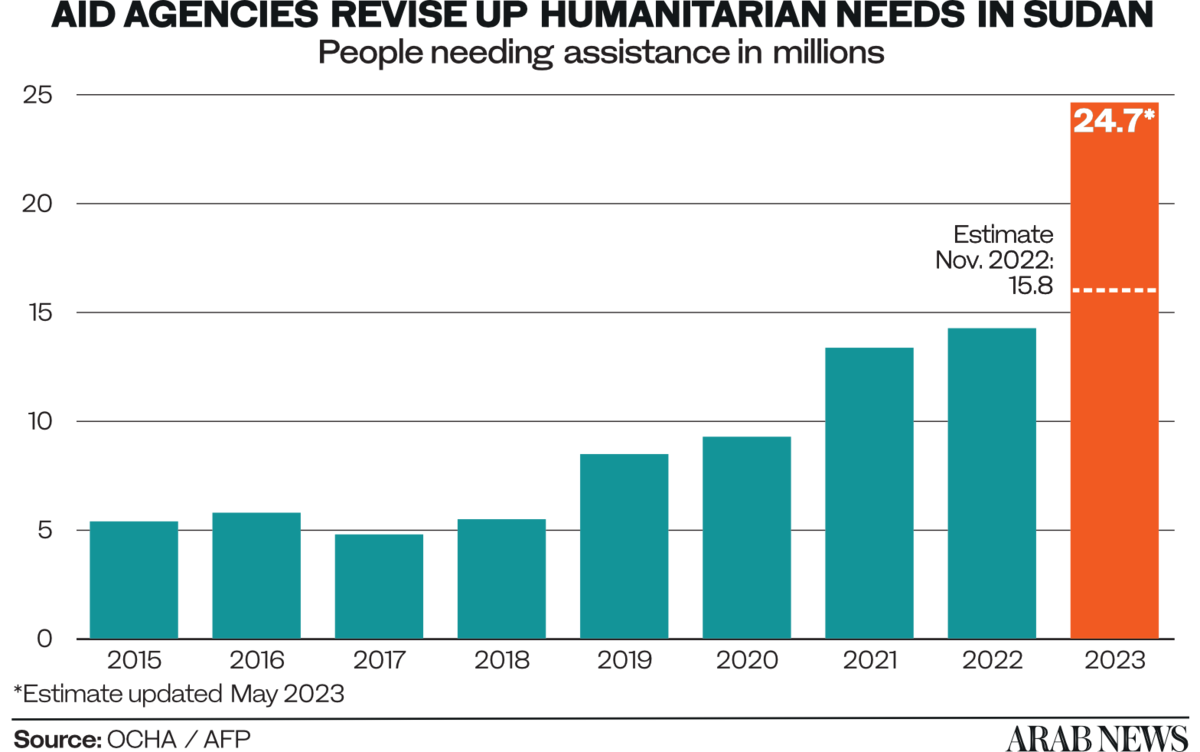

According to UNHCR, there have been 42,300 documented arrivals in Egypt to date, although the true figure is likely far higher. The UN agency estimates around 300,000 people could arrive over the coming months.

The ongoing conflict in Sudan has had a devastating impact on women and girls, who are among the most vulnerable demographics in times of violent upheaval everywhere in the world.

Women and girls displaced by the fighting in Sudan are at risk of rape as a weapon of war or falling prey to human traffickers. Indeed, the RSF’s predecessor, the Janjaweed, was implicated in similar crimes during the 2003-20 conflict in the country’s western Darfur region.

Reports and testimonials from the time concluded that the Janjaweed waged a systematic campaign of rape designed to humiliate women and ostracize them from their own communities.

Many female Sudanese political activists had already experienced gender-based violence, including rape, at the hands of security forces during the pro-democracy protests of 2019. The latest conflict has made matters far worse, with armed men accused of acting with complete impunity.

“Since the start of the hostilities, UNHCR and humanitarian protection partners have been reporting a shocking array of humanitarian issues and human rights violations, including indiscriminate attacks causing civilian casualties and injuries, widespread criminality, as well as sexual violence with growing concerns over risks of gender-based violence for women and girls,” Olga Sarrada Mur, a spokesperson for UNHCR, told Arab News.

“UNHCR is working with the governments of the countries receiving refugees from Sudan as well as with humanitarian partners to ensure all the reception and transit centers have staff trained to treat these cases in a confidential manner and provide survivor-centered services, including health support but also psychosocial support, counseling as well as legal aid services if needed.

“Sexual exploitation and abuse prevention measures are being developed in the new sites hosting refugees fleeing the conflict.”

Given the pace of arrivals in Cairo and other cities, any assistance for people displaced by the Sudan conflict may be too little. With Nishan and her family’s appointment at the UN still months away, they say they have received no help whatsoever, while their apartment in Cairo is paid for by a friend.

For those unable to escape Khartoum and other violence-torn areas, the situation is dire. Activists such as Al-Karib urge women trapped by the fighting in Sudan to remain vigilant.

“The RSF have been implicated in sexual violence for over two decades,” said Al-Karib. “The overall structure is very flawed, enabling all kinds of crimes against civilians to happen. Citizens must take the issue of protection into their own hands (and) provide broad guidance for women and girls to protect themselves and (their) communities from sexual violence.”

She added: “The truth is that sexual violence has been happening in Sudan, in conflict and post-conflict areas, for the past 20 years.”

According to her, the culture of impunity in Sudan, which has allowed such crimes to go unpunished, means the scale of the problem has been misreported, both regionally and internationally, for many years.

“The Sudanese regimes, including the transitional government, which took (power) after the 2019 revolution, have never addressed the issue of sexual violence and the perpetrators of sexual violence, who were mostly military forces and law enforcement,” Al-Karib said.

“They have enjoyed impunity and protections. Sudan has a very flawed and very problematic legal framework that constantly seeks to criminalize survivors of sexual violence, accusing them of adultery, and so on.

“This has led to the fact that sexual violence is now becoming normal — normalized — as are the perpetrators of sexual violence.”

Perpetrators often assume they are “invincible” due to this culture of impunity, added Al-Karib, “which is quite prevalent, particularly among the armed groups and the military.”

Gender-based violence is not the only issue impacting women and girls that aid agencies are trying to address amid the crisis in Sudan.

UNHCR says it is providing reproductive healthcare, with medical teams prioritizing assistance for pregnant and breastfeeding women, particularly in terms of nutrition.

Agencies are also monitoring the threat of human trafficking — already a concern in the east of the country prior to the latest bloodletting. “Conflict and disasters and the protection issues they generate create conditions for trafficking in persons to thrive,” said UNHCR’s Mur.

“Ongoing fighting limits the capacity to identify new victims, but mechanisms are being put in place by UNHCR and partners at border areas … to identify potential victims of trafficking.”

For Nishan and others who managed to escape to safety, all they want is peace and security. “All I wish from the world,” said Nishan, “is to see my children continue their university studies and then go on to work and live happily.”