Turkey’s Government Uses Disaster for Profit

The recent Kahramanmaras earthquakes killed more than 50,000 people in Turkey. But nature alone isn’t to blame. The impact of the quakes was exacerbated by decades of widespread corruption and misrule that created dangerously unsafe buildings in a quake-prone area. With at least 279,000 buildings collapsed or structurally compromised in southeastern Turkey, countless people have lost their loved ones, homes, and even entire towns.

The Turkish government’s urban transformation framework, which has been gradually developed since 2002, was supposed to facilitate the evacuation and reconstruction of the very buildings that came crashing down. Instead, research shows, urban transformation projects became a tool for the ruling party to displace and dispossess minority communities for economic growth and political control. The government has a track record of using post-disaster reconstruction for profit and gentrification of Kurdish cities, as exemplified by the cases of Van after the 2011 earthquake and Diyarbakir following urban warfare between Turkish military and Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) forces in 2015-16.

In Diyarbakir, for example, taking advantage of the destruction, the government evacuated Surici, the historical city center populated by Kurdish communities, and expropriated almost every single parcel of land. The government proposed construction of six new police stations and two observatory towers, along with tourist attractions in the old town, in an effort to uproot political opposition while also turning a profit.

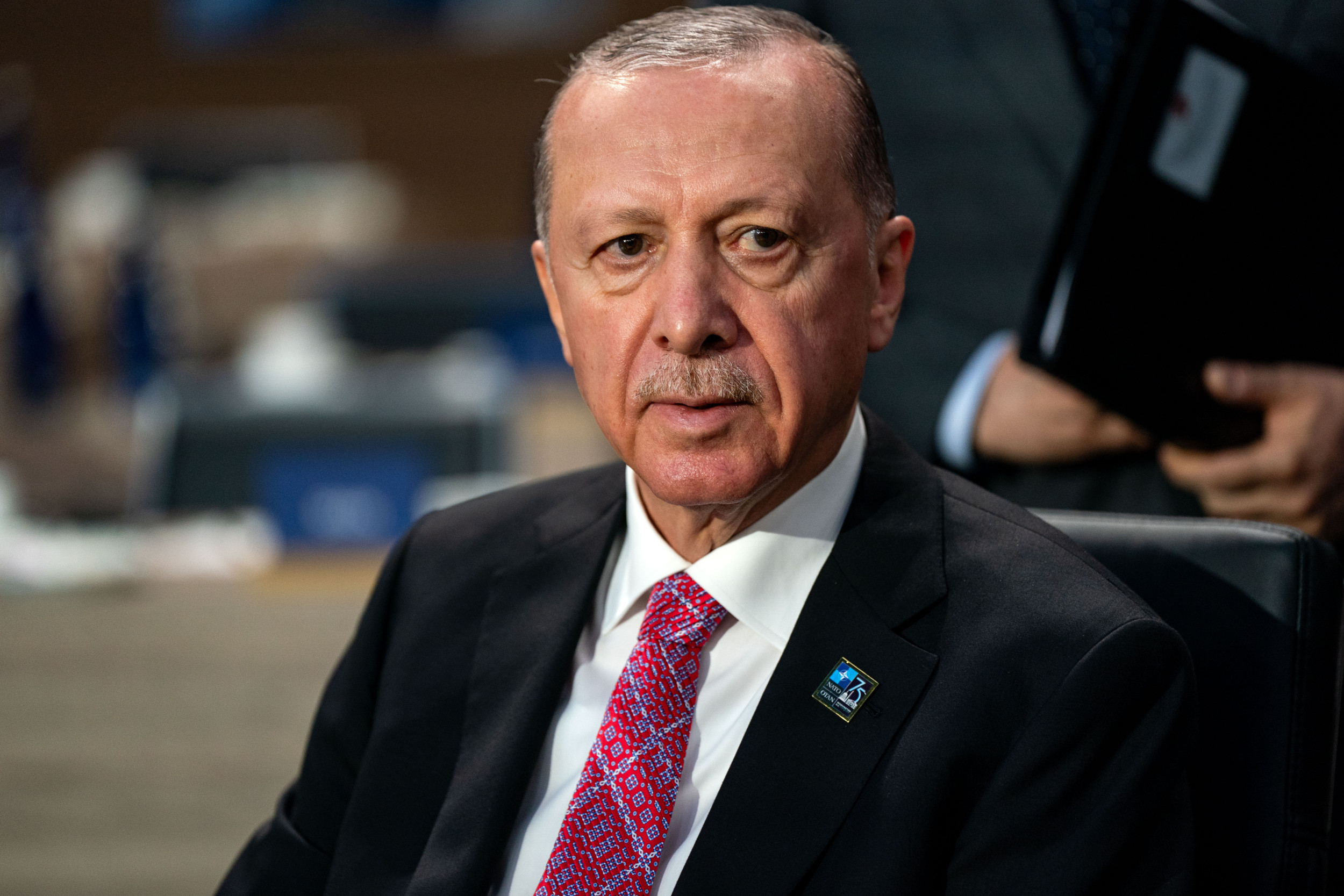

This year, as the May national election approaches, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan is already making promises to rebuild the earthquake-effected region in a year and rushing to break ground for 17,902 new buildings in 11 cities—without any transparency on how the reconstruction will be accountable or safe despite how some social housing complexes built for victims of past earthquakes are crumbling. Reconstruction will be disastrous if the government deploys its past post-disaster strategies in the region. Civil society, the political opposition, and the international community need to advocate for transparency, public accountability, and the meaningful inclusion of local communities in the creation and implementation of reconstruction plans for the region.

Turkey is a quake-prone country, and over the past two decades, the governing Justice and Development Party (AKP) has developed an extensive legal and organizational earthquake preparedness framework to, in theory, lessen the impact of disaster through urban transformation projects. Yet in practice, these laws have been used for political ends, not for disaster preparedness. One of the laws central to this framework is Law 6306, introduced in 2012, which gives the Ministry of Urbanization rights “regarding improvement, evacuation, and renewal … in areas at disaster risk.” Under the guise of readying for catastrophes, this law has been repeatedly used to target minority communities, justifying their forceful evacuation from urban centers (after which their neighborhoods are replaced with upscale residential and commercial areas).

Since its first term in power, the conservative and nationalist AKP has wielded urban policies to boost the economy through construction. To do so, it has portrayed religious and ethnic minorities such as the Kurdish and Alevi communities as either undeserving and greedy or violent and implicated in terrorism in order to get hold of valuable urban land. Urban transformation projects have torn down historical neighborhoods that offered social ties and resources fundamental to people’s survival, and which were hubs of political resistance with deep-seated know-how. By likening urban transformation efforts to the battle against terrorism, the government discredited oppositional figures and experts critical of its urban policies and even imprisoned them on accusations of espionage and attempts to overthrow the government.

Amnesties that forgive zoning and construction violations also take advantage of earthquake preparedness language. The most recent amnesties were enabled through the 16th provisional article added to Law 3194 in 2018. The provisional article cites “preparations for disasters” to justify amnesties, implying that these after-the-fact applications for construction permits will facilitate the identification of buildings at risk.

For AKP, these policies facilitated new alliances with businesses and voters. Urban transformation projects promoted new partnerships between the party and small- and mid-sized contractors. Meanwhile, zoning amnesties attracted new votes from individual property and business owners in the construction sector as the government provided permits retroactively without requiring them to bring the buildings up to code. Zoning amnesties are thus a selling point for the party, particularly in the run-up to elections. In fact, before the Kahramanmaras earthquakes brought southeastern cities crashing down, the Turkish parliament had been poised to decide whether to extend the scope of the zoning amnesties—right in time for the May general election.

Almost 295,000 buildings in the earthquake zone had been given permits through amnesties. The government refuses to comment on how many of these buildings were destroyed by the earthquake. However, about 52 percent of the buildings in the earthquake zone were built after 2001 and, according to emergency planning experts, if those buildings had been built to legal standards they would not have collapsed.

Besides profiting from construction violations, the government also spent earthquake taxes on building roads to stimulate the economy. Earthquake taxes were introduced after the devastating 1999 Izmit earthquake, and the government has collected over $36.5 billion of them over the past two decades. It has yet to report how this money contributed to disaster prevention and response efforts.

Zoning amnesty applications were a massive source of income, yielding over 25 billion lira (currently equivalent to more than $1.3 billion) for the government. Research shows that the government relied on urban transformation projects to revive the economy and create jobs at times of economic crisis. Based on data from the Turkish Statistical Institute, the construction industry’s share of Turkey’s GDP increased by 4 percent during AKP’s first 15 years in power.

The government’s abuse of the disaster preparedness and reconstruction industries is especially acute in southeastern Turkey, where the earthquakes hit. Erdogan has already put forth an executive order to give extensive powers to the Ministry of Environment, Urbanization, and Climate Change and its subsidiary Housing Development Administration (TOKI) to reconstruct the earthquake region. Yet this may result in a new wave of displacement and dispossession.

On paper, TOKI is responsible for building social housing for those who have been displaced by urban transformation projects and disasters. However, rather than functioning as a social housing agency, TOKI has worked more like a profit-driven, private construction company that builds massive subpar-quality apartment complexes in urban peripheries. For decades, TOKI has been claiming to give displaced citizens a chance to own apartments while in fact indebting them.

Soon after the 2011 Van earthquake, TOKI built 23,000 apartment units for the earthquake victims in an area where 48,666 structures collapsed or were heavily damaged. But after nearly 10 years, many of the residents were still unable to clear their debts. Some of them could not pay the monthly bills and thus were evicted.

The urban reconstruction process in Diyarbakir following the intense urban warfare of 2015-16 is another case in point. In the city’s Sur district, the governing party took advantage of the declared state of emergency to neutralize Kurdish local municipalities and expropriate land and property, which it used to build commercial and touristic spaces in neighborhoods that were once home to thousands of low-income Kurdish families. In return, the government provided the forcefully displaced inhabitants of Sur with the “opportunity” of either buying a TOKI apartment located outside of the city or receiving ridiculously low monetary compensation for their land and property.

The declared state of emergency and the sense of urgency facilitated by Law 6306 allowed the government to attribute arbitrary and very low real-estate values to the destroyed properties. The government also used the ambiguity and variety of property types (inherent to the informal settlements and slum houses common in low-income minority neighborhoods) to keep compensations low for the displaced people, while funneling money into the pockets of construction companies and subcontractors.

In the last 20 years, countless people have been displaced and continuously dispossessed by the urban policies of the Turkish government. The government may use the Kahramanmaras earthquakes as a basis for displacement and dispossession in other parts of Turkey as well. Turkey sprawls over an active fault system and is laden with millions of structurally unsound buildings.

Earthquakes may occur naturally, but many of their consequences are human-made and political. The Republic of Turkey is commemorating its 100th year, and the impact of the recent earthquakes is enmeshed in a century-long history of structural and physical violence carried out by the Turkish state against the Kurdish and Alevi people. Regardless of which party comes to power in the May elections, corrupt and authoritarian urban strategies are built into the institutional cultures of the Turkish state as ways of dealing with economic crises and sociopolitical opposition.

Today, civil society once again bears the brunt of the devastation, as volunteers work actively on the ground despite government efforts to repress documentation of the disaster’s impact. The Union of Turkish Bar Associations has filed criminal complaints against those involved in the construction and inspection of the collapsed buildings. As the government is rushing to remove the earthquake debris, civil society organizations and volunteers are persistently collecting evidence from the rubble to hold public officials and contractors responsible for the destruction in the region.

The levels of displacement due to the recent earthquakes are already heart-breaking and unimaginable. Preventing further displacement and dispossession demands urgent change in the Turkish government’s urban transformation and reconstruction policies.