Turkey spars with China over Uyghurs, but is it real?

Turkey has acknowledged an ebb in ties with China over Beijing’s treatment of its Uyghur minority, but President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s record suggests he will try to avoid any move that could damage relations.

At home, Erdogan faces protests by the Uyghur diaspora over allegations that Uyghurs who are wanted by Beijing are being handed over to China. The Turkish president is also under pressure from the opposition to take a firmer defense of the Muslim minority inhabiting China’s Xinjiang region. The Uyghurs’ Turkic origin resonates strongly with Turkey’s nationalist quarters, including the base of the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), the de facto coalition partner of Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP). The issue is often brought up in parliament by the Good Party in a bid to corner the government and the MHP, with which it shares nationalist grassroots.

Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu blamed Beijing last week for “slowing down” any progress in the bilateral relations, Anatolia news agency reported. A recent UN report has documented China’s human rights violations in Xinjiang, and Turkey “cannot but react” to such breaches, he stressed.

President Xi Jinping proposed five years ago that a Turkish delegation visit Uyghurs camps in Xinjiang to see the situation on the ground, but the Chinese authorities have since insisted that such visit could take place only on their terms. “Why would we be a tool of Chinese propaganda?” Cavusoglu asked. Also, he said, Turkey will not extradite any Uyghurs who have acquired Turkish citizenship, dismissing reports of extraditions as “an absolute lie.”

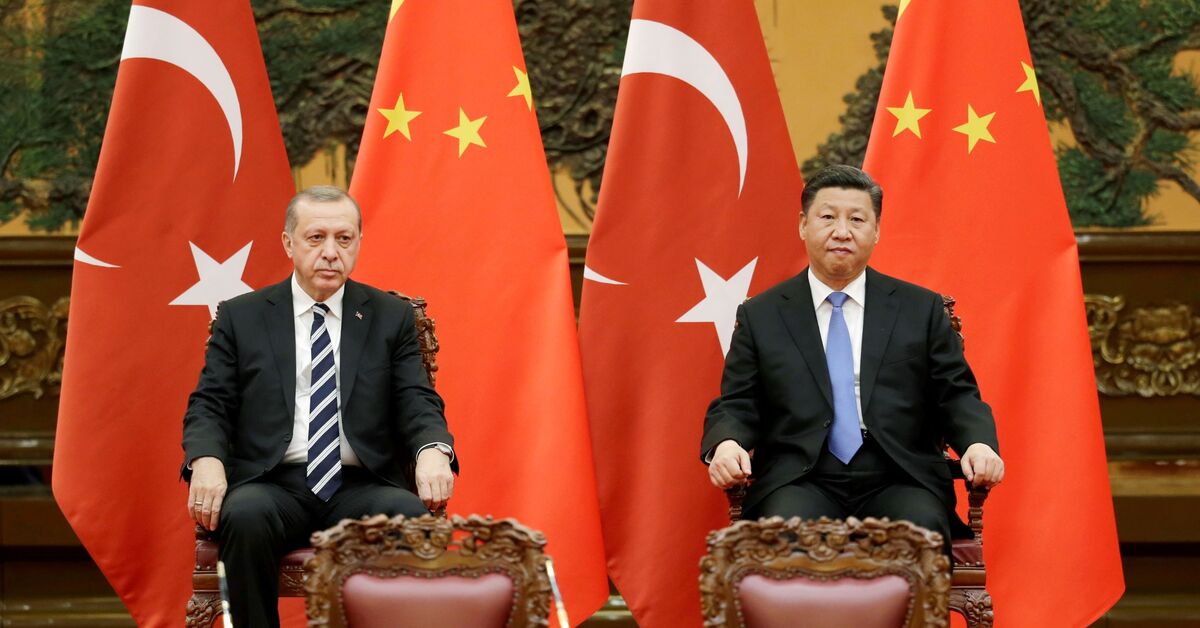

Erdogan last visited Beijing in July 2019 amid growing international outcry over reports that hundreds of thousands of Uyghurs were confined in “re-education” camps.

The Uyghur issue has remained a thorn in Turkish-Chinese ties over the years. Erdogan infuriated Beijing in 2009 when he said that the killings of Uighurs in Xinjiang amounted to genocide. But in April 2012, Erdogan, then prime minister, became the first Turkish premier to visit Beijing in 27 years and the first ever to go to Urumqi, the capital of Xinjiang.

A fresh crisis hit in early 2015 as the Chinese authorities arrested 10 Turkish nationals on charges of providing forged Turkish passports to Uyghurs to flee the country. On a visit to Beijing in July 2015, Erdogan asserted support for China’s territorial integrity and denounced the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM), a Uyghur separatist group in Xinjiang. China has held Turkey responsible for the entrenchment of al-Qaeda- and Taliban-linked ETIM members in northwestern Syria.

Cavusoglu’s 2017 visit to China seemed to be a turning point. The minister asserted that Turkey would not allow any activities targeting China, stressing that it had designated ETIM as a terrorist organization.

But is the outrage real?

Yet Beijing had reasons to doubt Ankara’s policy on ETIM. In a fundamental contradiction, al-Qaeda- and Taliban-linked Uyghurs have been able to take shelter in Turkey, while exiled Uyghur leader Rebiya Kadeer was denied a Turkish visa. Nonetheless, Beijing appeared willing to overlook such discrepancies as the AKP blocked a series of parliamentary motions to probe the alleged persecution of Uyghurs.

On the economic front, Chinese companies acquired a 65% stake in the Kumport port in Istanbul and a 51% share in a new suspension bridge over the Bosphorus, while the China Export and Credit Insurance Corporation offered up to $5 billion in insurance support to Turkey’s sovereign wealth fund. Erdogan has hoped also for Chinese financing for his controversial project to build an artificial waterway as an alternative to the Bosphorus.

Yet, developments often draw Ankara into the fray. In November, for instance, a deadly fire in Urumqi sparked protests in Turkey amid claims that lockdown restrictions hampered the rescue efforts. In a NATO meeting that month, Cavusoglu said Beijing had failed to provide a convincing explanation about the fire. Also, the government found itself on the defensive after a policeman was filmed warning Uyghur protestors outside the Chinese consulate in Istanbul that they “will be swept away by force” before being detained and deported.

Cavusoglu’s latest criticism of China might have surprised the opposition as well, given Turkey’s silence when the UN Human Rights Council voted against holding a debate on rights abuses in Xinjiang in October. The government had come under fire at the time for doing nothing to convince Muslim countries to back the proposal.

Erdogan remains hopeful of sharing in China’s Road and Belt Initiative, and his declaration in September that he seeks Turkish membership in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization appears to only increase his reliance on Xi.

In sum, Ankara is torn between the sensitivities of China and the nationalist anger at Beijing at home. The government’s occasional rebukes of China seem to be aimed mostly at relieving its ally and appeasing the grassroots. Some Uyghur activists, too, remain unconvinced of Ankara’s support, as evidenced by posts on social media accusing the AKP of hypocrisy.