Turkey in Georgian art: Modernists from Tbilisi to Istanbul

The most famous artist from the republic of Georgia was a rustic country fellow whose death in 1918 coincided with the independence of the nation that had wrested its freedoms from the Russian empire, only to be annexed by the Soviets in 1921. But those three years were preceded and followed by waves of creativity among poets and painters, friends and enemies who charged ruthlessly over the edge of history, balancing on that precipice known as modernism, its revolutionary aesthetics confounding all sense of time and place.

The unmistakably brilliant, magical surrealist canvases of Niko Pirosmani adorn the walls of the heady establishment on Rustaveli Avenue, the main artery in Tbilisi. In the bustling Central Asian capital, lofty examples of 19th-century architecture open to galleries enriched by such naive genius as that which has given the modest Caucasus country its unique character, a visual signature among contemporaries. His oils recall that of Marc Chagall and Paul Gaugin, and spread out into adjacent, high-ceilinged rooms beside the artworks of his peers.

In 1918, ecstatic by their newfound liberty, bristling with pride in their self-determination, painters frequented the art cafes of Tbilisi, and styled themselves like Parisians, Western as any Frenchmen on the town, out for a rout of cultural abandon. Pirosmani may have died that year, but he would be posthumously well-known. He’d lived in rural poverty. According to certain biographical depictions, he learned to paint by making signs on restaurants when not running a dairy shop surrounded by roadless hills and wayward herders.

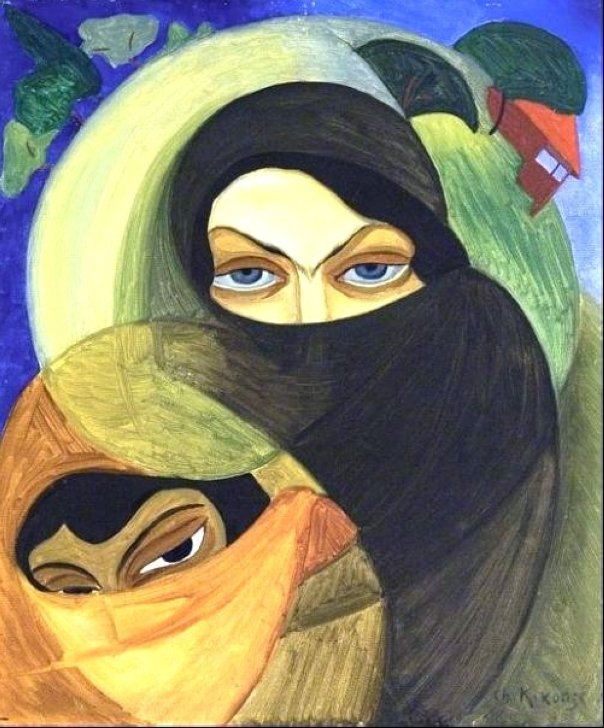

In 2007, Istanbul’s Pera Museum hosted a Pirosmani exhibition, naming him a legend in naive art, by that meaning, an autodidact, formally uneducated. But the age in which he lived was ripe for discovery as avant-garde intellectuals streamed into Tbilisi and its environs from Russian cities, crossing the mountainous land border that Georgia shares with its aggressive northern neighbor. At the National Gallery of Georgia, curators and art historians are hard at work contextualizing the art of Pirosmani within wider circles of early 20th century creatives.

In a Tbilisi artist collective

The makers and producers of art in newly independent Georgia, that was, during its initial era of national sovereignty, had confidently communistic airs, even if they would soon be overrun and supplanted by Bolsheviks. They formed unions, collectives, orders and groups, affirming their ideological consolidation not only among their Georgian brethren but also with Ukrainian poets, Russian progressives, any and all like-minded sort who shared their sense of direction on the canvas, the sculpture block, out of the studio and in life.

Naturally, many burst into disagreements, dissolving their associations. In between organizing exhibitions, new factions formed. As early as 1877, the Fine Arts Society developed into the first School of Painting and Sculpture in 1901. But not until 1916, with the founding of The Society of Georgian Artists would modernists come together. Only, it was like herding cats, and they rarely hung on to formal institutionalization outside of their personal artistic training and the ways in which they rebelled against its rules and laws to make way for novel ideas.

Avant-garde artists, who took up the front of some of the more rarefied experimentation among modernists, did not make organizing any easier. In 1921, however, their Paris exhibition was a triumph. They included the beloved Lado Gudiashvili, Alexander Salzmann and others who represent pioneering artistic invention from Georgia a century past. One of the important modernist collectives was The Futurists’ Syndicate, which had Kirill Zdanevich as a member. His art is now in the permanent collections of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA).

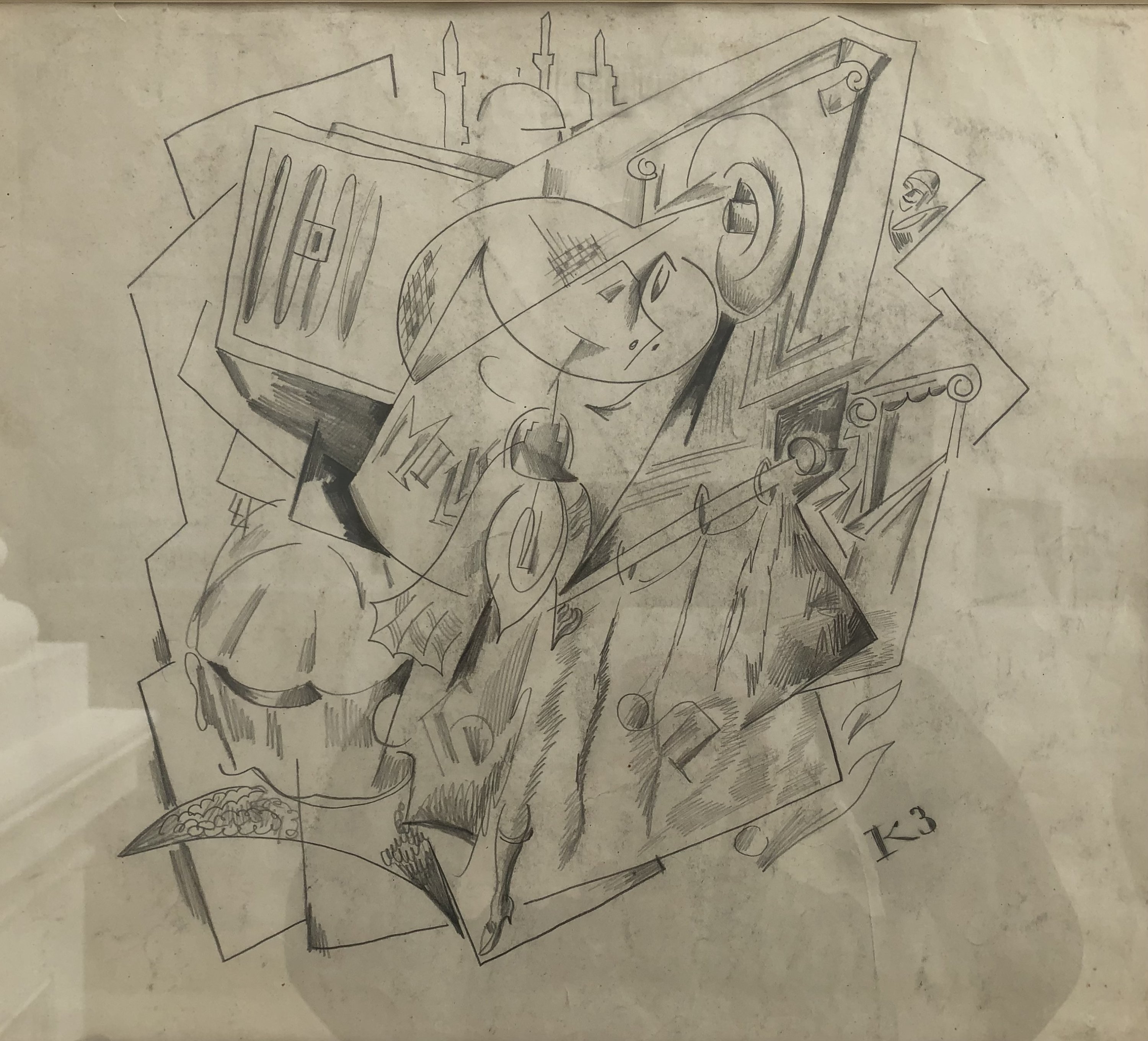

The National Gallery of Georgia showed a number of his works for their recent show, “Georgian Modernism and Tbilisi Avant-Garde,” such as his pencil on paper drawing from the 1910s, entitled, “The Istanbul.” It is a graphic parallel to the cacophonous din that the then imperial capital of the late Ottoman empire would have conjured for one such as Zdanevich whose perspective was born of an increasingly urbanized, industrialized, Soviet takeover from the relatively pastoral scenography that Pirosmani was crafting. Zdanevich infused his work with elements of advertising imagery, Cyrillic typographies, and nonfigurative abstraction.

Toward latitudinal solidarity

Zdanevich had a brother, Ilya, who, as the National Gallery of Georgia historicizes, was quite a venturous type, not only in his artwork, but in carrying the social significance of artists working together. After the breakup of The Futurists’ Syndicate, he led the formation of another collective called “41 degrees” apparently because their native Tbilisi shares the same latitude with New York, Madrid, Naples and Istanbul, where their colleagues were breaking the rules of picture-making, while exploring pragmatic aesthetics with their modernist imagination.

During their active years, the freewheeling avant-garde prompts to forego beauty and representation in painting, or meaning in poetry, in the interest of expressing the total awe of being through sound, color and action, captured the minds and hearts of Tbilisi’s artists, as it did everyone who walked through its bohemian streets. But not all artists were so radical, and while based in Tbilisi, some stayed true to the more conventional leanings of the earlier group, “The Society of Georgian Artists,” such as Georgian painter Valerian Sidamon-Eristavi.

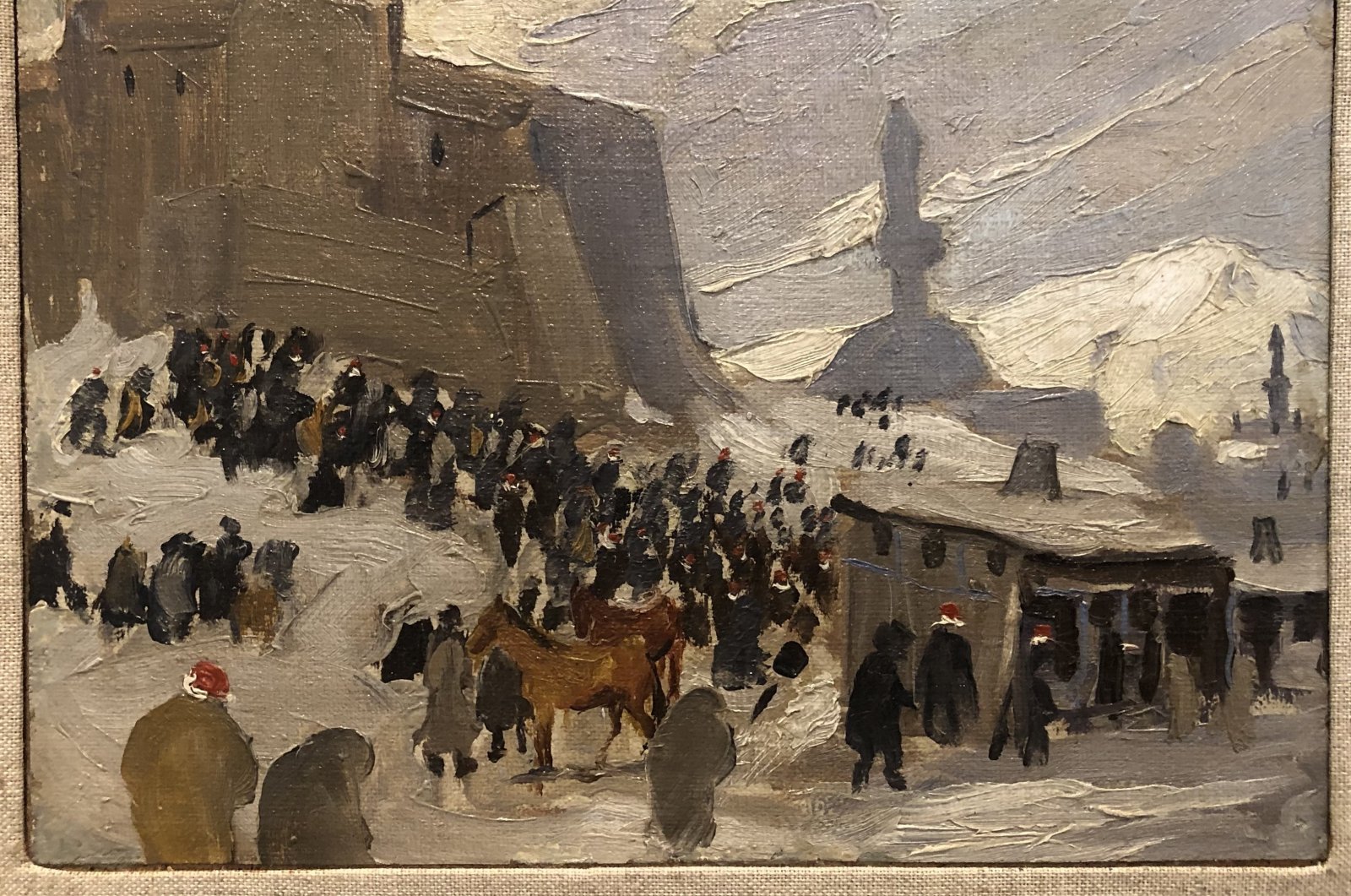

In posterity, Sidamon-Eristavi enjoys renown as perhaps the first of theater designers in Georgia when plays were vehicles for unorthodox thinking. They were enacting their visions for the future, as it were, and employed the stoutest minds who were already deep in the waters of ideological distinction when it came to image-making. Sidamon-Eristavi in particular imbued landscapes with political and historical meaning. His series of small oils, “Erzurum, Etude,” painted while on the Ottoman-Russian front in 1916, details his skills as a keen observer.

As early as the 1820s, the traveler and French consul Jacques François Gamba wrote: “Merchants from Paris, couriers from St. Petersburg, tradesmen from Constantinople, Englishmen from Calcutta and Madras, Armenians from Smyrna, or Yazd, Uzbeks from Bukhara – all would gather in Tbilisi during a day.” In an academic study on Tbilisi’s art history, “The Fantastic Tavern and Other Caucaian Stories (1916-1921)” scholar Maria Tsantsanoglu noted how the 41 degrees was comparable to the dadaist scene in Paris.