The Web Foundation is working to counter deceptive design – TechCrunch

The Web Foundation‘s Tech Policy Design Lab is working on an interesting-looking project to counter deceptive design — aka dark patterns* — with the goal of producing a portfolio of UX and UI prototypes which it hopes to persuade tech companies to adopt and policymakers to be inspired by as they fashion rules to make the online experience less exploitative of web users.

The Design Lab was launched last year to be the “action arm” of a wider Web Foundation initiative, announced back in late 2018 — when the not-for-profit digital access group proposed a “Contract for the Web” ahead of the 30th anniversary of World Wide Web founder Sir Tim Berners-Lee’s invention.

Kaushalya Gupta, its program management lead — who also heads up the Tech Design Lab — told TechCrunch that the goal for the deceptive design patterns project will be to bring “human-centered design” to bear on critical web interactions.

The project will fed by collaborative discussions involving a range of industry and user stakeholders, via a series of workshops taking place later this year, to co-design the prototypes. The hope is to end up with a series of pro-user interface design templates that will stand as benchmarks to nudge how tech platforms shape and mould these critical (and all too often cynically configured) decision/interaction pipelines.

“The Lab is a place where people’s experiences drive policy as well as product design,” explains Gupta. “Where solutions take into account the full diversity of those who use digital tools. And in terms of our policy development approach it is informed by design thinking and human-centered design.”

Work to spec out the deceptive design patterns project was preceded by a survey, as the Lab polled the thousands of organizations and entities signed up to the Contract to decide what should be its first focus — whittling some 200 “promising topics” down to deceptive design.

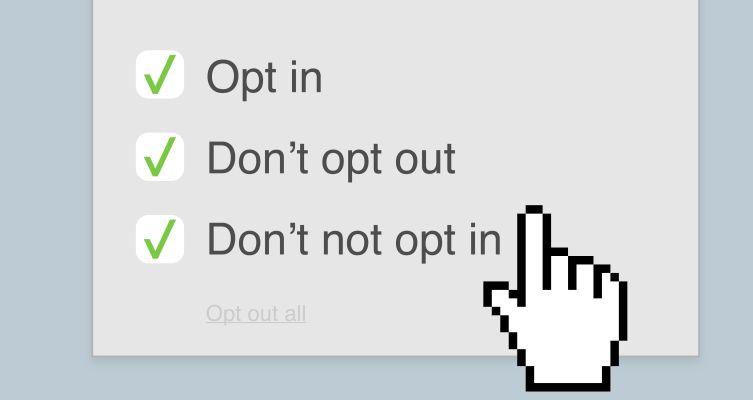

Western internet users may be most familiar with deceptive design patterns in a niche like cookie consent banners which typically (intentionally) fail to offer parity between the ease of agreeing to give up your privacy to the data industrial adtech complex and refusing tracking — making the latter horribly hard (if they even offer that choice at all).

There are also plenty of shamefully familiar examples in e-commerce too.

Just look at how aggressively Amazon nudges users toward inadvertently agreeing to sign up to its subscription-based Prime membership scheme — teasing a carrot of free shipping at the point of purchase in a bid to distract the shopper from the simultaneous sleight of hand as shipping is only free if you also agree to sign up to a free trial of Amazon’s Prime scheme, after which the e-tail giant will start to bill you for what is normally a paid service. (And of course it also makes users go on a not-so-merry dance through multiple menu layers to find the button to cancel Prime if you inadvertently sign up for this “free” shipping/trial.)

But Gupta makes the salient point that deceptive design is also rampant in the global south where design tricks may also, she emphasizes, be disproportionally harmful — given there may be many more web users with relatively little online experience getting subjected to this cynical, tricksy stuff, who are not so accustomed to the “usual tactics”, making it harder for them to detect and avoid dark patterns and the harms that flow on from them.

People in the global south may also be more likely to have to access the internet through smaller devices, she also notes — which can make deceptive nudges easier to pull off. Less screen real estate means it’s likely harder to spot what’s really going on.

“One example from India is about this edtech company, called Byju,” says Gupta. “They have these subscriptions that look like free at first glance. And now there are thousands of unassuming parents who are actually trapped in debt because they’re trapped into these subscriptions.”

The pandemic edtech boom has likely exacerbated the volume of harm flowing from such deceptive subscriptions. “A lot of these people actually come from quite humble backgrounds, they’re not really all that rich — so to be trapped into subscription has been [very harmful],” she adds. “Here we’re talking about debt — so this is where the issue of dark patterns goes from being annoying or frustrating to actually impacting people’s lives and savings.”

Gupta argues that it’s not for want of examples of consumer harm that practical action to try to counter deceptive design has been relatively limited to date — with perhaps the most focus on the topic coming from academics.

(That said, data protection regulators in Europe have also finally started paying attention — with some major enforcements around bogus adtech consent flows in recent months; while, just this week, the European Data Protection Board put out guidelines on spotting and avoiding dark patterns in social media interfaces, along with a call for feedback.)

“The challenge with deceptive design is it’s such a nebulous space,” suggests Gupta. “I think that’s what’s been limiting action in this area — because it’s so nebulous. It’s such a big grey area.”

Part of the Lab’s work will therefore be on trying to nail down a scope that’s “not too broad so that we can’t really create impact — and not too narrow where the exercise becomes redundant”, as she puts it.

“Through the consultation sessions [we’ve held so far] — in terms of priorities — people are most interested in tackling data protection issues as well as consumer protection,” she continues. “So our focus is definitely going to be on consumer protection but we’re also going to be seeing how we can establish cross-cutting teams and address the most important issues under data protection and privacy as well. We’ll try to tackle a range of harms.

“In terms of specific industries [we may focus on] or not, we’ve been speaking to people across different industries and groups to identify a wide range of harms. Right now we’re synthesizing all of our findings and working with the design firms to create the workshops.”

Gupta says the Lab expects to have prototypes ready to present by late summer — after which it hopes to engage policymakers with the detail of what’s been developed.

And of course the work won’t stop there; the Lab will also be pressing for adoption of the (non-deceptive) design templates — such as by seeking commitments from tech firms to, at least, test them.

Gupta points to an earlier project — focused on online gender-based violence — which she says led to commitments from a handful of tech giants to trial recommendations, adding that the Lab is continuing to follow up on those pledges.

How much success does the Lab expect for a project which, if it’s to really move the needle away from exploitation, will need to convince scores of tech firms to reset their default design imperatives — from a “growth at all costs” revenue-focused mindset to cultivating “ethical growth” and fostering a more respectful relationship with web users by prioritizing their agency and welfare?

“Yes of course we’re hoping for success,” she responds, before deflecting the direct question into a description of how the Lab intends to measure success — saying it will benchmark results on “adoption” (i.e. uptake of non-deceptive design suggestions); as well as “sustainability” — which means finding partners who will be able to carry the work forward once the Lab moves on to new projects; and on “accountability”, meaning the follow up element (i.e. did firms really carry through and stick with reformed designs?) will be key.

“We’ve found a lot of interest, for example, in terms of ESG [environmental, social and governance],” she also notes, discussing potential uptake. “Companies like venture capital firms are interested in having a questionnaire so they can screen out companies who use deceptive design.

“It’s interesting because there are so many different applied uses [of non-deceptive design principles] — that could be applied across different industry sectors and that’s what we’re focused on.”

As noted above, we are finally seeing some privacy-focused regulatory action in Europe against cynically designed defaults and “no choice” screens that infringe on consumer autonomy — with a number of complaints and investigations into problematic design patterns also being driven by consumer protection watchdogs. (See, for example, a major series of complaints against TikTok last year.)

Europe is a region with longstanding consumer protection and data protection legislation which should be able to lend consumers a degree of shielding against manipulative interfaces — yet a historical lack of enforcement has allowed the problem to be seeded online, spread and become entrenched on the modern web. A purge is well overdue.

On that front, EU lawmakers are now picking up the baton — and proposing to further beef up consumer rights in this area. Such as by incorporating explicit bans on dark patterns into major incoming digital regulations (although it remains to be seen whether such details survive trilogue negotiations which are ongoing to hash out a final agreement between the EU’s trio of institutions).

Child safety is another area where lawmakers on both sides of the Atlantic are now paying a lot more attention to how to outlaw manipulative and/or hyper-addictive interfaces which target children, such as design tricks that nudge minors to weaken privacy protections, hand over lots of personal data and/or relentlessly pester them for attention to rack up more revenue.

Another interesting development in the interface navigation space that’s been proposed by privacy campaigners in recent years, and attracted some attention from lawmakers, is the potential to use automated tools to help users navigate hostile menus — such as privacy campaign NGO noyb’s suggestion for an advanced, user-configurable control layer in the browser; or a recent research project out of ETH Zurich proposing to automatically filter and block non-essential cookies so that consumers don’t have to keep wasting their time saying no.

A U.S.-led publisher coalition also revived a browser level privacy signal effort back in 2020 — with the goal of building momentum for a global standard to make it easier for web users to signal opt outs of the sale of their data to businesses.

However such automated approaches don’t pretend to be panacea that can universally tackle the scourge of deceptive web design in every place it rears its ugly head — as they really need relatively narrow and/or specific fields of application (not to mention legal mandates) to stand a chance of functioning as intended. Whereas disingenuous menus and choice screens can pop up all over the darn place.

A genuine cure will need tech companies to be willing to turn over a new leaf en masse — and/or be shamed into it by ethically minded rivals getting there first.

What do tech companies tell the Lab when asked why they keep choosing to deploy all these cynically deceptive designs?

“Um, that they’re working on it,” responds Gupta with a little hesitation as she chews on the question. But she quickly follows up by blaming the siloed structure of many tech firms as an integral part of the problem.

“What’s interesting is that there are product teams, there are policy teams — and so the designers aren’t really working with the policy people. And so even the work in companies takes place in silos. So when we want to work with companies it’s not that their UX designer is creating a deceptive design — it’s like everyone is part of a bigger picture and what the user ultimately experiences is deceptive design,” she tells us. “I think these things are actually perpetuated from the university level — where designers [and other professionals, such as engineers] aren’t taught about these things.

“One great thing is Stanford, for example, in fall this year they’re launching a pilot course on deceptive design and tackling that. And that’s great to see a university is actually doing something… What’s important is to look at the entire life cycle. These things start off at the university level, they get perpetuated when people join the industry. And I think the way people work inside the industry is what also exacerbates the issue — because no one is ultimately responsible.”

So while Gupta believes there is rising awareness among design professionals of the concept of ethical (and thus unethical) design — and that “a lot of designers are actually doing their best to learn more about it and see how they could apply it in their work” — she also argues that “when it comes to [acting ethically] at a company level it’s challenging because of the silos”.

This is why the Lab’s outreach for this project already involves speaking with people from a variety of different teams, not just designers. And why the role corporate structure itself may play in programming and perpetuating deceptive design is likely to end up being an important focus for the project.

“It also means working together with the UX designers, with the product teams, with the policy teams,” adds Gupta. “And that’s also been something that’s interesting when we’ve reached out to companies; identifying the right person to speak to in the company it’s a process. When we’ve been engaging governments we know who to engage with. With civil society, it’s very easy to get engagement with them. With companies, there’s a lot of complexity about finding the right person to engage with.

“Once we have been speaking with them they’re very supportive of taking part in the workshops — so I think the fact that they’re even willing to have a conversation at this point is a small win… but of course we definitely need commitments and we need to hold them to account.”

The Lab is asking tech firms and other stakeholders who want to register an interest in the project — and potentially participate in the upcoming workshops — to fill in this online form.

*The Lab is intentionally avoiding use of the term “dark patterns” for this project, in favor of the more accessible/less obscure descriptor “deceptive design” — which both neatly explains the problem and does not inadvertently reinforce negative linguistic stereotypes (i.e. that dark equates to bad).