Storm deaths ‘could have been prevented’, Indigenous leaders say

Honor Beauvais’s every breath was a battle as a snowstorm battered the Rosebud Sioux Reservation in the US state of South Dakota.

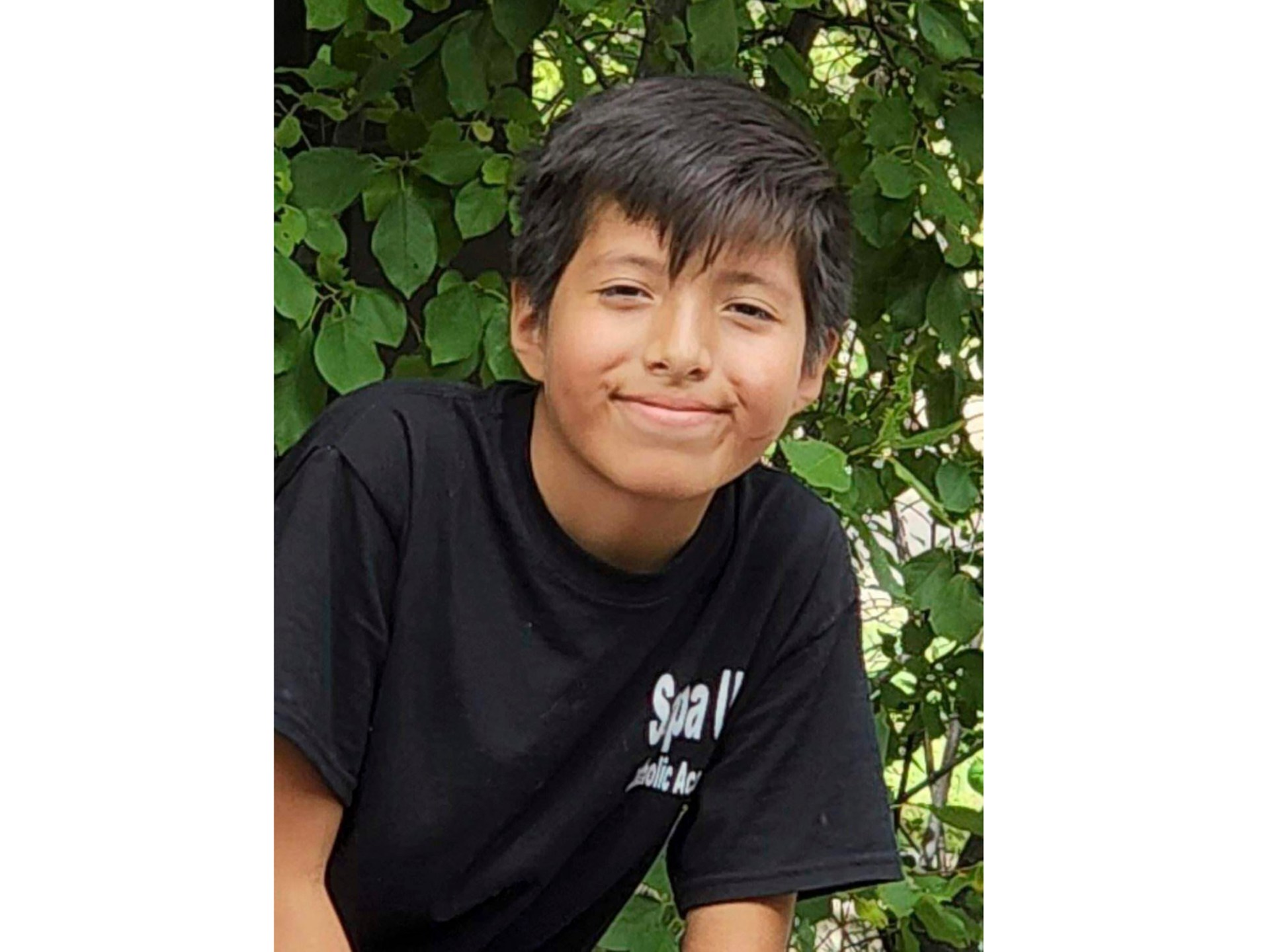

The asthmatic 12-year-old’s condition had been worsening as his fragile lungs fought a massive infection brought on by influenza. His worried aunt and uncle begged for help clearing a path to their cattle ranch near the community of Two Strike so that emergency services could arrive.

But when an ambulance finally managed to get through, Honor’s uncle was already performing CPR, said his grandmother, Rose Cordier-Beauvais.

Honor, whose Lakota name is Yuonihan Ihanble, was pronounced dead last month at the Indian Health Service’s hospital on the reservation, one of six deaths that tribal leaders say “could have been prevented” if not for a series of systemic failures.

The community has expressed frustration at South Dakota’s Republican Governor Kristi Noem, the United States Congress, the Indian Health Service and even, for some, the tribe itself.

“We were all just in shock,” said Cordier-Beauvais, who recalled that, when the snow finally cleared enough to hold the funeral, the family gave out toys to other children as a symbol of how he played with his siblings. “He loved giving them toys.”

As the storm raged, families ran out of fuel, and two people froze to death, including one in their home, the Rosebud Sioux Tribe said in a letter this month seeking a presidential disaster declaration.

The letter described the situation as a “catastrophe” for the reservation, located in a remote area on the state’s far southern border with Nebraska, about 210km (130 miles) southeast of Rapid City.

In a scathing State of the Tribes address delivered last week in the state legislature, Peter Lengkeek, chairman of the Crow Creek Sioux Tribe, accused emergency services of being “slow to react” as tribes struggled to clear the snow, with many using what he described as “outdated equipment and dilapidated resources”.

Noem’s spokesperson, Ian Fury, said the claims were part of a “false narrative” and “couldn’t be further from the truth”. The Indian Health Service did not immediately return email messages from The Associated Press news agency seeking comment.

Noem, who is seen as a potential contender for the 2024 presidential race, declared an emergency on December 22 to respond to the winter storm and activated the state’s National Guard to haul firewood to the tribe.

But by then, the Rosebud Sioux Tribe was worn out from a series of storms that had started about 10 days prior. The weather was so severe that tribal leaders ultimately rented two helicopters to drop food to remote locations and rescue the stranded.

The firewood, said OJ Semans, a consultant for the tribe, came in the form of uncut logs, which were not immediately usable. The tribe wrote in its letter that volunteers continue to work diligently to get the wood cut.

“It was a political stunt that did nothing to help the people that were in trouble,” he said.

It all started on December 12, when the tribe shut down offices so people could prepare for the first onslaught. The storm hit in earnest around midnight, dumping an average of nearly 60cm (24 inches) of snow on the reservation, most of it in the first day, said Alex Lamers, a National Weather Service meteorologist.

By the time the storm let up on December 16, the reservation also was coated with 6mm (a quarter inch) of ice. Wind gusts as high as 89 kilometres per hour (55 miles per hour) had blown the snow into drifts of up to 7.6 metres (25 feet).

The tribe issued a no-travel advisory, except for emergencies, threatening a $500 fine for violators. Still, some residents travelled and got stuck, their abandoned vehicles creating a hazard for first responders, the tribe said.

Starting on December 18, soon after the blizzard moved out, there were 11 straight days with sub-zero temperatures. Wind chills were dangerous, hitting -46C (-51F) at their lowest. The length and severity of the cold made it one of the worst such stretches on record, Lamers said.

Then, as fierce cold and storms descended across much of the rest of the country, claiming at least 40 lives in western New York state, a phenomenon called a ground blizzard hit the reservation on December 22. Strong winds blew existing snow on the ground, and visibility fell to 400 metres (a quarter mile), Lamers said.

The Bureau of Indian Affairs sent staff to help, and the White House said the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) also spoke to the tribe’s president. But snowploughs were paralysed in the cold, with the freezing temperatures turning the diesel fuel and hydraulics into a gel, the tribe said.

Shawn Bordeaux, a Democratic state legislator and a former tribal council member, was running out of propane heat at his home on the reservation when Noem announced she was sending in the National Guard. Unable to get out and shop, he had no Christmas gifts for his children. Even for those who could get out, the store shelves were growing bare. Gas stations were running out of gas.

“I don’t want to totally dog out the system, but we kind of got left to our own devices,” said Bordeaux, a frequent critic of the governor. “She basically left us hanging.”

The tribe also alleges that Congress is at fault for not changing rules that allocate how money from a tribal transportation programme is distributed among the nation’s 574 federally recognised tribes.

Semans, the tribal consultant, said the programme’s reliance on making determinations based on tribal enrollment hurts the Rosebud Sioux. While its enrollment of 33,210 members is relatively modest, its land base of approximately 360,170 hectares (890,000 acres), spread across five counties, is vast.

That meant there simply was not enough equipment to respond, said Semans, who lost two family members in the storm.

One of them, his 54-year-old cousin Anthony DuBray, froze to death outside, his body found after Christmas.

The other victim, his brother-in-law Douglas James Dillon Sr, called for help during the first storm because his asthma was flaring up. But getting to the hospital would have meant being carried about 400 metres (a quarter mile) over snowbanks to a deputy’s patrol car.

Semans said a glimpse outside showed it was “almost impossible” to travel that far, so Dillon went to bed. He died on December 17 at the age of 59.

Semans and his wife, Barbara, were snowed in for 15 days, using a propane space heater to ward off the cold after losing power. They were dug out just in time to make it to Dillon’s funeral 11 days after his death.

“Even angry doesn’t reach the level of the neglect,” Semans said. “This was an atrocity.”

For Honor, who was beloved as a jokester, his illness came at the worst possible moment of the storm.

It was December 14, and his aunt, Brooki Whipple — with whom he spent weekdays as she and her family lived close to his school — was growing frantic as Honor struggled to breathe.

The family pleaded for help, and finally a snowplough cleared the road to their ranch. Cordier-Beauvais said Honor and his uncle, Gary Whipple, set off immediately for the hospital just 4.8km (3 miles) away.

There, Honor was diagnosed with influenza and sent home despite the fact that Cordier-Beauvais called and told hospital staff that the family wanted him admitted because they were worried about getting out again as snow continued to fall.

By the next day, Honor was still struggling — and the roads were impassable.

“Due to the high winds,” the Rosebud Sioux Tribe Highway Safety warned that day, “the routes plows make are quickly being filled back in.”

Cordier-Beauvais, the tribe’s business manager, stayed on the phone with her worried daughter, who had delivered a baby boy just days earlier, praying through the hours-long effort to get help clearing the road.

But the help came too late.

A doctor called to break the news to Brooki, who was home with the baby and her daughter, who was so close in age to Honor that their family called them “the twins”.

“In our Lakota way, they’re brothers and sisters. Inseparable,” Cordier-Beauvais said.

“She was not handling it well. Of course, she’s a child and Brooki was so stressed out. But she had her baby, and had to tend to them. And it was just awful.”

With no break in the weather, Honor was not buried for nearly four weeks.

At the funeral, Cordier-Beauvais recalled how her basketball-loving grandson’s closest friends were pallbearers.

“They all just miss him so much,” she said.