Sea monster ‘Mosasaurus’ in Türkiye? How a 1999 find rewrote paleomap – Türkiye Today

The fossil of Mosasaurus hoffmanni, known as the “dinosaur of the seas” or “cousin of the dinosaurs,” discovered in Kastamonu, Türkiye, 2024. (Photo collage by Türkiye Today team)

June 04, 2025 04:31 PM GMT+03:00

It was 1999 when a sharp set of fossilised teeth and jawbones hidden beneath the rocks of Kastamonu’s Devrekani district quietly altered Türkiye’s place in paleontological history. The discovery, made by Professor Cemal Tunoglu of Hacettepe University, marked the country’s first-ever marine reptile fossil—and not just any reptile, but Mosasaurus hoffmanni, a fearsome predator from the Late Cretaceous seas.

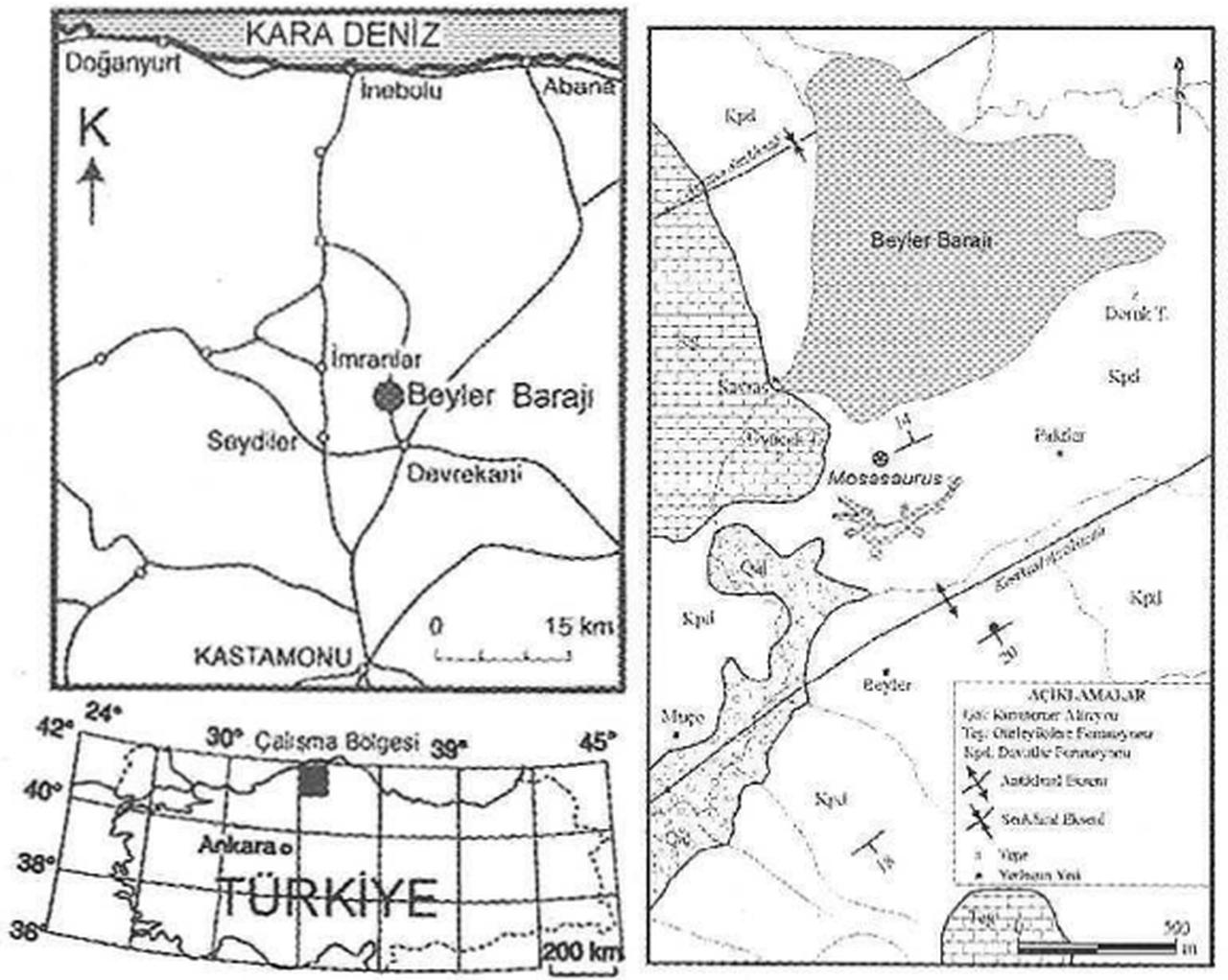

The fossil, found near the upper sluice of Beyler Dam, comprises a partial skull, including the left and right jaws and a series of 5 to 7 cm-long conical teeth, consistent with one of the largest known marine reptiles of the dinosaur era. Though uncovered more than two decades ago, the find continues to hold scientific significance today.

The fossil of Mosasaurus hoffmanni, known as the “dinosaur of the seas” or “cousin of the dinosaurs,” discovered in Kastamonu, Türkiye, 2024. (AA Photo)

A predator from depths of time

Mosasaurus hoffmanni was a 17.5-meter-long marine reptile that lived between 70 and 65 million years ago, just before the mass extinction that wiped out the dinosaurs. This giant of the seas likely preyed on fish, ammonites, and other marine creatures, using its powerful jaws and snake-like swimming motion to dominate its habitat.

“Back then, it was a completely unexpected find,” Prof. Tunoglu recalled in his study. “We knew of marine fossils in Türkiye, but not vertebrates from the Cretaceous. This changed that.”

Published initially in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology in 2006 by Tunoglu and co-author Nathalie Bardet of France’s National Museum of Natural History, the discovery placed Türkiye on the global Mosasaur map for the first time.

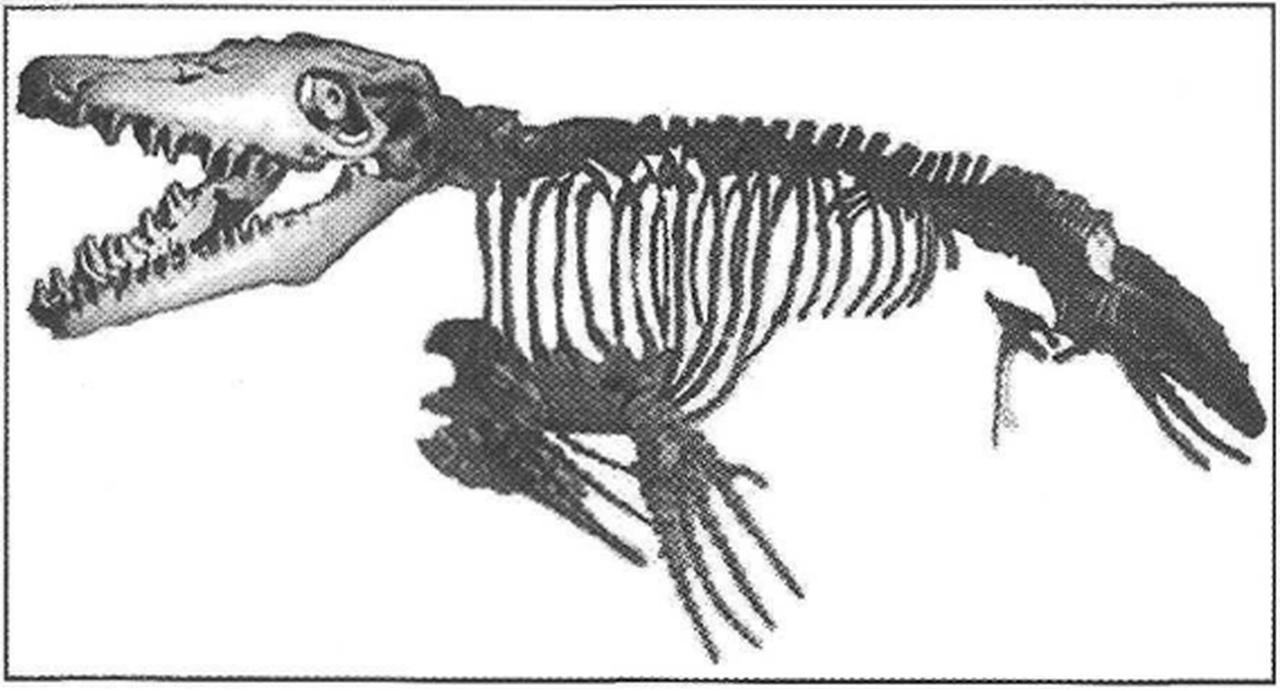

A life-size skeletal reconstruction model of Mosasaurus hoffmanni (Mantell, 1829) in the Natural History Museum of Maastricht, Netherlands. (Photo via Geological Bulletin of Türkiye/1999)

Global rarity, regional first

Prior to this discovery, Mosasaurus hoffmanni fossils had only been recorded in the United States, the Netherlands, Belgium, Poland, and Bulgaria. The Kastamonu find became the first in Türkiye and all of Western Asia, offering crucial evidence that these enormous reptiles once swam in the ancient Tethys Ocean that covered Anatolia.

The fossil came from the upper Maastrichtian strata of the Davutlar Formation, a geologic unit rich in marine invertebrate fossils. But it wasn’t until this vertebrate discovery that scientists could confirm the presence of apex marine predators in the region during the final days of the Cretaceous.

Location and simplified geological map of the study area. (Photo via Geological Bulletin of Türkiye/1999)

Achance discovery that changed paleontology

The fossil was uncovered during geological fieldwork near the construction site of the Beyler Dam. The area has since been shaped by infrastructure development, raising concerns about the loss of other potential finds.

What’s remarkable is that the skull section found—around 1.5 meters in length—may represent only a **fraction of the entire skeleton**, which has never been recovered in full.

“This was likely less than 5% of the entire body,” Tunoglu noted. “The rest may have been destroyed or lost during excavation works.”

The fossil of Mosasaurus hoffmanni, known as the “dinosaur of the seas” or “cousin of the dinosaurs,” discovered in Kastamonu, Türkiye, 2024. (AA Photo)

An ongoing call for fossil awareness

The Mosasaurus discovery remains a cautionary tale for construction projects across fossil-rich regions like Türkiye. Paleontologists stress the need for **collaboration between engineers and geoscientists**, especially in areas with known geologic significance.

“We’re talking about a creature that swam these seas 70 million years ago,” Tunoglu emphasized. “If we don’t pay attention during development, we risk losing pieces of Earth’s deep history forever.”