People of colour struggle to escape Russian invasion of Ukraine

Záhony, Ukraine-Hungary border – After six years in Ukraine, Ayoub, a 25-year-old Moroccan pharmacy student, had built a life he was proud of in Kharkiv, a city in the country’s northeast. He learned the Russian language, which is widely spoken in the city of 1.4 million, studied Ukrainian culture, and made friends from around the world. He was due to graduate in three months, but Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has forced him to flee the country, and exposed him to a level of racism he had not previously experienced.

Initially, he had planned to wait out the invasion in Kharkiv, hoping the Russian assault would stop. But when that possibility appeared increasingly unlikely, he joined classmates to make a long trek across the country to the Polish border.

In Lviv, a city 80 kilometres (50 miles) from the Polish frontier, it became clear to Ayoub that he, along with other non-white international students, would be stopped by Ukrainian guards from leaving the country.

“They wanted Ukrainians to go first, so it was white people who got priority. Taxi drivers were also charging us crazy money, but I thought there will always be opportunists, even in war. It wasn’t until I reached one of the ‘checkpoints’ on the approach to the Polish border that I was actually pushed back and told to wait,” he told Al Jazeera.

Instead of waiting, he decided to try crossing into Hungary, where he arrived on Wednesday.

“When I spoke to the guards in Russian, they told me I should be speaking Ukrainian and questioned whose side I was on. That was really upsetting because I had worked so hard to learn Russian, not just speak it, but read and write it as well.”

Universities across Ukraine have attracted international students due to the high-quality education on offer for relatively low fees, ranging between $4,000 and $5,000 a year.

Students from countries such as India, Nigeria, and Morocco have helped to make Kharkiv a vibrant university city and their fees have contributed to the local economy. Many have stayed in Ukraine after graduating and taken jobs in the country’s hospitals and businesses.

But some international students said their schools did not offer them assistance to leave the country as Russian forces launched the invasion. In an email seen by Al Jazeera, dated February 24, the day of the invasion, students at one university received an email notifying them that classes would move online. Two days later, students at the same institution received an email announcing a “vacation” from February 28 to March 12.

“No one helped us to leave or coordinated anything, we were just left on our own,” said Deborah, a 19-year-old student from northern Nigeria. She asked Al Jazeera not to use her real name.

“My friends went to the Polish border and were treated awfully by the Ukrainian guards. It wasn’t just Black people like me; it was anyone who wasn’t white,” she added.

In a statement issued on Wednesday, the Ukrainian Ministry of Foreign Affairs refuted allegations of discrimination by border guards and said it operated on a “first come, first served approach” that “applies to all nationalities” with priority given to women, children, and elderly people in accordance with international humanitarian law.

Ayoub is annoyed that his teachers still expect him back in class on March 12. “I understand they want to keep morale high, but I am afraid they will charge us, or stop our studies if we don’t go back. I don’t understand why they cannot just suspend everything until further notice.” The experience has been so emotionally draining, Ayoub doesn’t think he will ever feel the same way about Ukraine again.

It is a sentiment shared by Deborah and her sister Aliyah, 19, who also studies in Ukraine. “This country has given me so much. The people of Ukraine don’t deserve this war and like everyone, I cannot understand why this has happened. Seeing pictures of these beautiful cities being shelled is awful. But I’ve seen a side that I cannot forget,” Aliyah added.

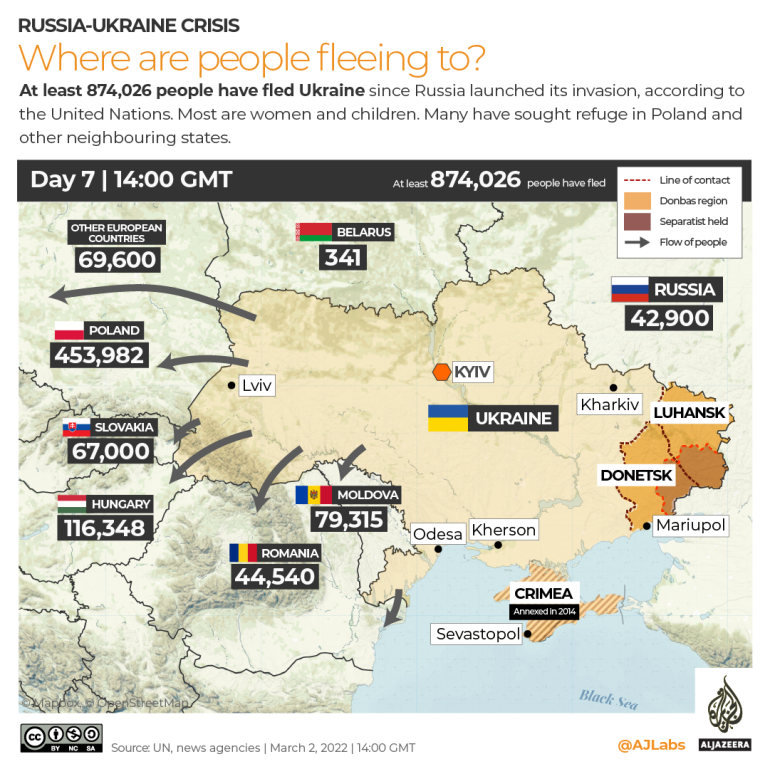

In recent days, word has spread among the international students fleeing Ukraine that they will likely have an easier time crossing into Hungary than Poland due to the smaller numbers of people waiting to get in. Of the refugees Al Jazeera spoke to, none reported problems boarding a train to the small Hungarian village of Záhony.

“I can see when you’re under crazy pressure and your country is being attacked you can act in terrible ways, but at the end of the day, everyone was running from the same danger,” said Deborah.