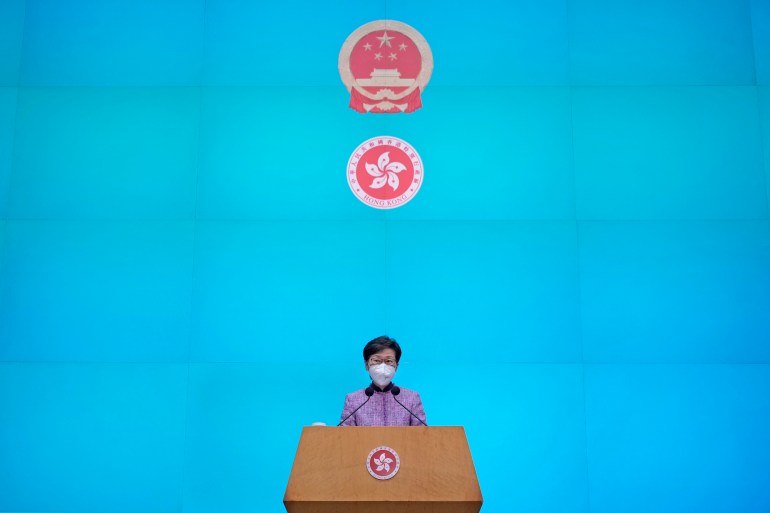

Lam steps down as fractured Hong Kong faces more uncertainty

When Carrie Lam became Hong Kong’s chief executive in 2017, she promised to heal a society divided by the Umbrella Protests of three years before. But as her term comes to an end, and former policeman and security chief John Lee takes the reins, the Chinese-controlled territory appears more fractured than ever.

The freest city in Asia that attracted international finance, news outlets, artists, civil society, and even welcomed foreign judges to its bench is now looking more and more like mainland China.

After years of growth, Hong Kong’s population has shrunk at a record pace over the last two years fuelled by the political crackdown as well as the harsh but ineffective measures to contain COVID-19.

Lam leaves office with a net approval rating of 33.4 percent, according to an April survey by the Hong Kong Public Opinion Research Institute, while just 16 percent of people report satisfaction with the current political situation and nine percent with the economy.

Hong Kong’s downward slide – and Lam’s probable legacy – can be traced to one key event in 2019 when she attempted to change the city’s extradition laws. The plan would have allowed residents to be extradited to China to stand trial, where defendants face a 99 percent conviction rate in criminal cases. At the time, Lam said the plan would close “loopholes” in the city’s extradition law. Instead, she set off Hong Kong’s largest ever protests.

Millions marched against the proposals, but with Lam’s government failing to respond and police using more heavy-handed tactics, the movement began to call for democratic reform. Confrontations between protesters and police increased, culminating in the prolonged siege of the Polytechnic University in November 2019.

The pandemic – and the restrictive laws imposed to control even the tiniest outbreak – put paid to the protests in 2020, but later that year, Beijing imposed the broadly worded National Security Law, which it said was necessary to deal with issues such as “terrorism” and “collusion with foreign powers”, but effectively silenced any form of criticism.

Backsliding or inevitable?

When China took back Hong Kong from the British in 1997, it committed to what it called “one country, two systems”, a framework under which the territory would be able to maintain its way of life and freedoms for at least 50 years.

While Hong Kong had already changed a great deal when Lam took over as chief executive, observers say its slide over the past two years was not inevitable.

Before the 2019 protests, Chinese President Xi Jinping had made clear he had big plans for Hong Kong. He wanted to integrate the city into the “Greater Bay Area” southern China megalopolis, but had not yet pushed for major changes, said Steve Tsang, director of the SOAS China Institute in London.

Xi only acted when he saw what he considered an “open rebellion” under way in Hong Kong.

“The protests would not have happened without Lam rushing through the extradition bill and did so very badly,” Tsang said by email. “Many if not most of the changes in [Hong Kong] since 2020 would come, but they would not have been introduced and imposed the way they have been without Lam’s particularly poor management of policies” like the extradition bill.

Lokman Tsui, an activist and fellow at the University of Toronto’s Citizen Lab, agrees.

“If you look back, I think the critical moment was the extradition bill, and that was not inevitable at all. It was hubris by the Hong Kong government, by Carrie Lam, that got us where we are now,” he told Al Jazeera. “The extradition bill wasn’t something apparently that Beijing was pushing, but that Carrie Lam was trying to push on her own initiative because she wanted to do well with Beijing.”

Even in the early days of the protests, when first one and then two million took to the streets on consecutive weekends, Tsui said the chief executive still could have taken a different path – as her predecessors had done in the face of public opposition.

In 2003, after a protest by 500,000 Hong Kongers the government shelved then-plans for national security legislation. The government also backed away from a 2012 plan to add pro-China “moral and national education” classes to school curriculums after students and parents protested.

Lam may have hoped the anti-extradition protests would go the way of the Umbrella Movement. In 2014, thousands of protesters had made global headlines as they occupied Hong Kong island’s Central business district to demand universal suffrage, but despite a strong start the protests eventually fizzled out.

What Lam failed to recognise – like many Hong Kong leaders before her – was that each time protesters had returned home in the past, their discontent had not gone away, said Citizen Lab’s Tsui. Instead, the feeling metastasized, he said, as Hong Kongers saw a growing disconnect between their interests and that of the Beijing-approved government.

“What the lesson of history teaches you basically trade in temporary compliance – people seem to be complying, or being obedient – but you lose trust, you lose good faith in government, and so on,” Tsui said.

Reading the tea leaves

As a career civil servant who was appointed to her posts, observers say that the odds were always stacked against Lam.

She was also placed in the “impossible” job faced by all chief executives of serving both Beijing and Hong Kong, she also lacked important political skills typically gleaned by leaders in democracies over multiple election cycles.

Much of this came from the “founding contradiction of Hong Kong,” said Ben Bland, author of Generation HK and director of the Southeast Asia programme at the Lowy Institute in Australia, whereby Hong Kong could not be both a democratic city and part of the world’s largest authoritarian state.

In the years leading up to the 2019 protests, “forces were bubbling up” as Hong Kongers and the Chinese government became increasingly frustrated with each other, he said.

Missing these signs, Lam failed to appreciate that a wave of Hong Kong nationalism had begun spreading through the younger generation in the years after the Umbrella Movement. Many began to appreciate their city’s unique cultural and political heritage, while more radical Hong Kongers wanted to push for more autonomy and even independence.

Grievance-specific protests also began to evolve into protests rallying against the entire political system, said Michael C Davis, a global fellow at the Wilson Center in the United States, as protesters began to link issues-based problems with their lack of representation in government.

“It’s always the street guarding Hong Kong’s autonomy, and not these public officials. [Chief Executives] Tung Chee-hwa, Donald Tsang and Leung Chun-ying are all guilty of this,” said Davis. “In some ways, Carrie Lam seems to be the most egregious player in this regard, pushing things through over public objection consistently. The impression then left was that she basically was taking instructions from Beijing.”

Bland also said during that time many Hong Kong officials seemed to be “clueless” in 2019 as to why protesters were on the streets, he said, and what could be done to reconcile with them.

“They just didn’t want to see what was happening on the ground,” he told Al Jazeera. “Officials in the mainland, they tend to view protesters as ‘Oh, they’re just spoiled children,’ and there was that public narrative. I think they ended up believing things they said publicly, which was a big problem.”

But Lam not only alienated the protest-going public, said Anna Kwok, the strategy and campaign director at the Hong Kong Democracy Council in the US.

“The 2019 movement and the way [Lam] handled it, raised a lot of questions from the Beijing government and even the pro-Beijing camp in Hong Kong,” she said, as many feared they could lose their seats in the then-semi democratic local elections.

The protests also put Hong Kong and Beijing in the spotlight as local and international media covered the events in minute detail for months.

Despite widespread public criticism, Lam has always maintained publicly that she was only ever trying to “fix legal loopholes” with her bill and has complained about the difficulty the protests wreaked on her personal life, unable among other things to use banking services after the US sanctioned her.

In private, a leaked audio recording in 2019 revealed that she would have preferred to quit than serve out her term as chief executive.

After Sunday, she will finally get her chance to rest.