Jollibee, Philippine icon, accused of exporting poor pay, conditions

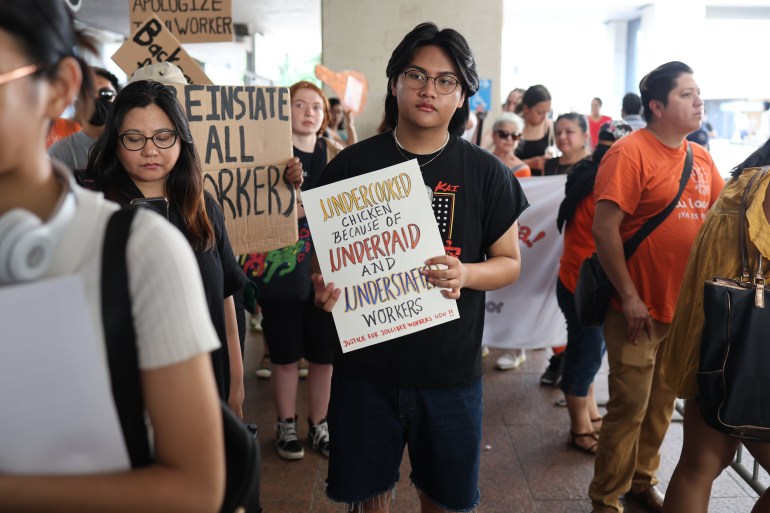

Metro Manila, Philippines – On July 6, National Fried Chicken Day in the United States, Vincent Cruz and a crowd of supporters marched into a Jollibee’s branch in Journal Square, New Jersey.

Cruz and 50-odd employees and supporters wanted to get the attention of management and customers alike on the busiest day of the year for the Philippine fast food chain.

Cruz is among nine Filipino former employees at the Journal Square branch who claim they were terminated by Jollibee management in February after petitioning for better wages and working conditions.

Standing in front of the cashier, the 19-year-old former fry cook held up a megaphone and yelled the demands of the new “Justice 4 Jollibee Workers” campaign, including reinstatement, back pay, an apology from Jollibee and a hike in the base pay from $14 to $17 an hour.

“For all fellow workers who have experienced or are currently experiencing similar struggles, we want you to be brave and take action,” Cruz, who migrated to the US in 2021, told Al Jazeera.

For Cruz, whose family back in the Philippines consider Jollibee a beloved brand, his alleged treatment by the company was “extra heart-breaking”.

Jollibee, which specialises in fried chicken and other fast food, is one of the most iconic Philippine brands.

The chain operates more than 6,500 branches worldwide, about half of which are located outside the Philippines.

In the first quarter of 2023, Jollibee Food Corporation (JFC) posted revenue of about $1bn – which was up 28.5 percent from the previous quarter – 20.2 percent of which came from North America.

JFC has announced plans to add 500 more stores in the US, which has by far the largest overseas population of Filipinos, in the next five to seven years.

In 2021, Esquire magazine ranked Jollibee as the 13th-biggest fast-food chain in the world and the only non-American company in the top 15.

But the Journal Square workers say that Jollibee is not just exporting its popular Filipino fast food but a record of unfair labour practices as well.

Since they launched their campaign, workers from more than a dozen other branches in the US and even the Philippines have reached out to them with negative experiences.

Jollibee’s Journal Square management has argued that the layoffs were necessary due to financial difficulties, a claim Cruz and the other workers say makes little sense when considering the branch hired 13 new employees two weeks after their firing.

Cruz and the other workers have filed a complaint with the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) and are waiting on the outcome of its investigation into whether the company violated their right to organise to improve their working conditions.

“Hopefully, the NLRB will be sympathetic. To us it’s a very slam-dunk case – it’s obvious that Jollibee violated labour rights,” Jackie Mariano, a lawyer with the advocacy group Mission to End Modern Slavery, told Al Jazeera.

In a statement to Al Jazeera, Jollibee North America said the layoffs had been a purely financial decision related to the conditions at that branch.

“The action was due to financial circumstances specific to this store and not related to other claims being circulated online,” a spokesperson said. “With its location near a commuter hub, the Journal Square branch has not recovered from customer behaviour changes after the pandemic, including people working from home instead of offices.”

On July 14, Facebook took down the “Justice 4 Jollibee Workers” campaign page, citing the use of the Jollibee logo as a “violation of community standards”.

Mariano said Jollibee is notorious for a practice in the fast food industry known as misclassification, where workers are retained as part-time staff indefinitely despite usually working close to full-time shifts. The practice allows an employer to avoid granting staff benefits such as paid leave and full-time wages.

Cruz said that his managers often extended his break hours to keep his working hours just below the eight-hour threshold even as he worked extra shifts, and burdened him with extra responsibilities, such as lifting heavy items in the stockroom, without additional pay.

“At 14 dollars an hour, you can barely survive living so close to such a Metropolitan area where everything is super expensive,” Cruz said.

In February, Jollibee-owned Smashburger was ordered to pay damages to 241 employees after being found to have violated New York City’s paid and sick leave laws.

“It’s Jollibee’s motive to maintain high profits by cutting labour costs,” Mariano said.

“That’s where they got all that capital, from unpaid benefits. It also relies on the labour export programme of the Philippines with 4 million Filipinos in the US comprising the company’s market base.”

Conditions at home

Allegations of poor labour practices at Jollibee stretch all the way back to the Philippines, where the company was founded in 1978.

Janine, who spent a year working at two Jollibee branches in Antipolo City in 2021, said she was denied overtime pay for shifts stretching from 3pm to 1am and would be forced to buy leftover food at the end of the day.

“I once had to take out three orders of spaghetti!” Janine, who asked to use a pseudonym, told Al Jazeera, adding that she earned 375 Philippine pesos ($6.65) a day, minus a 50 pesos fee ($0.89) for a recruiting agency.

As in the US, Jollibee in the Philippines has been accused of depriving employees of benefits and job security by keeping them as contract workers indefinitely.

In 2018, the Philippines’s Department of Labor and Employment (DOLE) said JFC topped the list of companies with the most contractual employees.

When DOLE ordered the company to regularise nearly 7,000 of its workforce, JFC submitted an appeal before laying off 400 workers.

JFC did not respond to a request for comment. But it has maintained in past statements that it complies with all labour standards and only deals with “reputable” contractors, insisting that the onus for regularising workers lies with the recruitment agencies.

In the same year, JFC chairman Tony Tan Caktiong told reporters that contractualisation was a thing of the past and had been supplemented by the outsourcing of employee roles.

Jerome Adonis, the secretary general of the trade union Kilusang Mayo Uno (KMU), said becoming a regular employee with a contractor and with the primary company are two very different things.

“How can you bargain for your full rights, wages and benefits with an agency which merely depends on the temporary contract between them and Jollibee for example?” Adonis told Al Jazeera, adding that workers do not enjoy an employee-employer relationship with Jollibee even if they are stationed at the company’s branches.

“That’s how it circumvents the law,” Adonis said.

KMU estimates that about 29,000 of JFC’s more than 36,000 employees are contractual, an increase since the DOLE’s 2018 directive.

Denise, who worked as a branch manager at JFC for 12 years, said that Jollibee usually handpicks a few workers who will be regularised directly with the company.

“It’s performance-based. You need to apply and then we evaluate,” Denise, who asked to be referred to by a pseudonym, told Al Jazeera.

Adonis, the trade union leader, said such a standard is “unfair and arbitrary”.

“They’re making workers compete for their own rights. They should be direct hires while their fundamental rights to unionise should be respected,” he said.