Iowa risks millions of dollars as it faces losing first-vote status

Des Moines, Iowa, United States – When Michael LaValle talks about the Iowa caucuses, he remembers the glory days.

He recalls when the likes of Peter Jennings and Tom Brokaw, major TV news anchors, would descend on the state, ready for wall-to-wall coverage of the caucuses, the first big event in the United States presidential primary calendar. His children got to meet legendary news host Dan Rather.

The 70-year-old event space manager has seen lots of change in the seven election cycles he has lived here – and from his perspective, it has not all been for the better.

More recently, there have been fewer visitors. And because of the nature of digital news, journalists and the campaigns sweep through in a couple of days rather than occupying hotel rooms for months on end.

But now that change is going to get a lot worse. This year, Democrats voted to shift their primary calendar, naming South Carolina — and not Iowa — as their first official party contest in all future presidential races.

LaValle is one of Iowa’s business owners decrying the decision because it will cost him. In previous presidential election years, Des Moines, the state capital, had seen its coffers boosted by as much as $11m in just the one week leading up to the caucuses.

The loss will not be felt much in the 2024 cycle. Republicans are still holding their first vote in Iowa in January, and Democrats are not holding a full-on primary contest, given that President Joe Biden faces few serious challengers from within his own party as he seeks re-election.

But LaValle doubts the state will see the hustle and bustle of election years such as 2016 and 2008 when neither party had an incumbent running and both spent heavily in the state.

After all, winning in Iowa at the time could set the tone for the rest of the primary season, signalling whether a candidate had popular appeal — or not.

LaValle has had a good perch from which to watch the change. Not only did he hold events for the likes of Barack Obama and Bernie Sanders, his uncle was pivotal in launching the caucus process back in the 1970s.

“My uncle Cliff Larson was the state Democratic chair who started the caucuses,” LaValle tells Al Jazeera.

The 1968 party convention in Chicago – coming just months after the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr and Robert F Kennedy – saw Hubert Humphrey and Edmund Muskie chosen for the presidential ticket.

But it also saw widespread protests and a harsh crackdown by Chicago police.

After this chaos, the party decided it had to find a better way to select a candidate, and Iowa was chosen to start the revised process.

Soon, the largely agricultural state would become known as a kingmaker, credited in 1976 with helping a dark-horse candidate take the White House: politician and peanut farmer Jimmy Carter.

Other candidates likewise found their prospects bolstered by the Iowa caucuses. George W Bush, for example, won the caucuses and then the presidency in 2000.

And in 2008, Democratic up-and-comer Obama came out ahead of Hillary Clinton in the party vote, a bellwether for who would prevail in the nomination contest overall.

Of course, candidates can lose in Iowa and still secure the nomination — Joe Biden proved that in 2020 — but those exceptions can be counted with a single hand.

‘Screening process’

The decision by Democrats to opt for South Carolina follows mounting pressure from activists to select a state more demographically representative of the nation and the party’s most loyal supporters, particularly African Americans. Iowa is 90 percent white compared with the national average of 71 percent.

South Carolina was also the stage for Biden’s dramatic comeback in the 2020 race, and Iowa did nothing to help itself by going through a technological meltdown on caucus night.

In a caucus people actually have to vote in person. In Iowa that means invariably on a freezing night in the middle of winter in gyms, church halls, community centres and sometimes people’s homes. They last for an hour or two, with people debating and making a case for the candidate of their choice.

Traditionally, totals were tallied by hand and the information forward to the party’s state headquarters. In 2020 Democrats used an app to help the vote count which didn’t record all the votes, leading to a manual count and massive delays.

For now there’s still a lobby in Iowa, including business leaders and Democratic politicians, saying the party should rethink its decision to relocate.

Greg Edwards is CEO of Catch Des Moines, the city’s convention and tourism body. He says it is impossible to calculate precisely the amount the caucuses generate.

“Nobody knows,” he says. “It’s obviously millions of dollars, and it’s over $11m that we can quantify here, just for the week leading up to the caucus with all the candidates and the media and all the hoopla and all of that, which we absolutely love.”

The businesses most obviously vulnerable are hotels restaurants and retail outlets.

Edwards says he hopes Democrats and others will lobby for Iowa to be returned to its first place on the starting grid.

One argument that Iowa’s champions make is that the state acts as a “screening process” for the candidates.

When candidates come to Iowa, they often attend smaller, more intimate events than they would in more populous states. They could be asked about anything from farm policies to the war in Ukraine.

South Carolina may also in time turn into such a process, but it is starting from scratch, having not played that role before.

Which state holds the first primary or caucus vote is important because if candidates do well there, it can give them a springboard onto New Hampshire and the other early voting states before Super Tuesday, the day when the greatest number of states hold primary elections and caucuses – with as many as a third of delegates up for grabs.

Critics of Iowa say because it is overwhelmingly white and heavily religious, it often benefits candidates pitching conservative ideas who are out of touch with the rest of the nation.

Democrats battle for seats

Questions about the caucuses’ future come as Iowa Democrats battle to rebound from nothing short of a crisis.

For the first time in 50 years, the state’s congressional delegation to Washington, DC, has been entirely made up of Republicans.

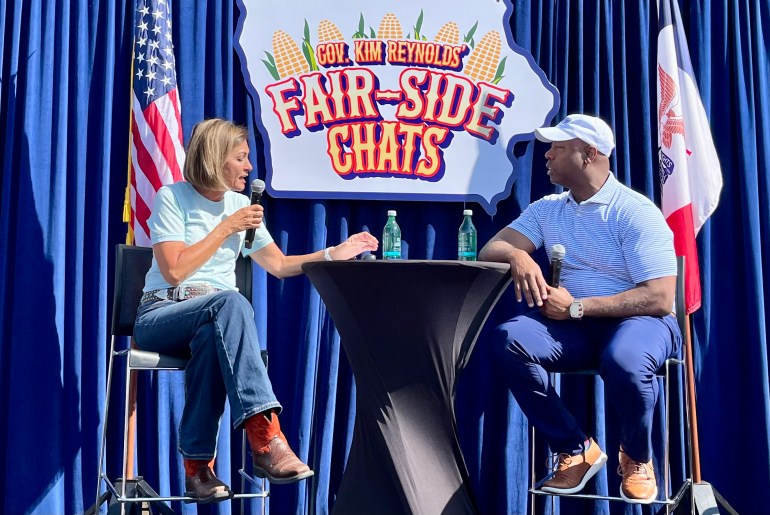

Popular Republican Kim Reynolds was last year re-elected to a second term as governor, and the GOP, or Grand Old Party, controls both houses of the state legislature.

The state Democratic Party did not respond to multiple inquiries about the caucuses and its challenges.

While Democrats have been reduced to just one statewide elected official – state auditor Rob Sand – the party recently enjoyed a surprise success in Warren County, 32km (20 miles) south of Des Moines, which Donald Trump won easily in 2020.

Democrat Kimberly Sheets beat Republican David Whipple to become county auditor, bagging 67 percent of votes after Whipple denied the 2020 election results.

Sheets says her victory was the result of hard work and the backing of a number of Republicans.

She believes Iowa is an ideal place to hold the initial presidential vote and says the impact of losing its first-vote status will be considerable.

“Because you get all your candidates to come, your followers, your news reporters,” she says. “It’s very exciting to see Iowa in the front of the papers. A lot of people think of Iowa and they think of corn and farmers.”

“Yes, that’s a big part of our culture,” she adds. “But we’re also big insurance companies. We’re CEOs. We’re philanthropists. There’s a lot that happens in Iowa that people aren’t aware of.”

Businesses fight back

Paul Rottenberg, a Des Moines businessman whose interests include the restaurant Zombie Burger, says the shifting of the caucuses will have an impact on hotels and restaurants.

“For any individual, there’s going to be some impact. Whether that’s a damaging impact or not, I think is questionable, and I don’t think it is,” he says.

He pointed out that the advent of digital news has changed the way the media covers the event: There are fewer journalists, and they stay for shorter periods of time. There are still good nights to be had, but they are unlikely to change the bottom line in a make-or-break way, he says.

“I’ve always felt like if your restaurant needed a big New Year’s Eve to succeed, you’re probably in the wrong business.”

Apparel company Raygun, which specialises in humorous designs, many of them with a liberal message, hopes to challenge how outsiders view the state.

“We really thrived off the interactions with the Democratic Party,” spokesperson Kat Correa explains. “Most candidates would even come by our location.”

While the company has managed to bounce back from the general downturn of Democratic interest in Iowa by diversifying its product line, it says overall traffic levels have “significantly decreased”.

Correa adds, “The Iowa caucus provided an opportunity for us to make our quick-witted T-shirt jokes. Now all the spotlight will be on South Carolina, and we don’t know how the products will be received.”