Indigenous people seek leadership, respect in biodiversity battle

Montreal, Canada – Indigenous communities are demanding a leadership role in the protection of global biodiversity, as a United Nations conference on saving critical ecosystems is putting a spotlight on the importance of Indigenous stewardship of land and waters.

Calls to put Indigenous rights and decision-making at the heart of biodiversity initiatives have grown louder as representatives from nearly 200 countries meet in Canada this month for talks aiming to hash out a plan to tackle the rapid decline of animals, plants and other organisms.

One million species currently face extinction, experts have warned, with various factors – including climate change and development projects – driving the destruction of lands, forests, oceans and other habitats.

A widely cited 2008 World Bank report (PDF) estimated that traditional Indigenous territories accounted for 22 percent of the world’s land and held 80 percent of its biodiversity – a reality that underscores the urgency of Indigenous leadership. Studies (PDF) also have shown that biodiversity is higher on Indigenous-managed land.

“Indigenous peoples are the principal guardians of the fauna and flora – and they best know what to do to protect [it],” said Dinamam Tuxa, executive coordinator of the Articulation of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil.

Speaking during a news conference on Friday morning in Montreal on the sidelines of the United Nations biodiversity conference, known as COP15, Tuxa said Indigenous voices must be at the heart of any COP15 biodiversity commitments to ensure that funding and other resources get to the communities at the forefront of the fight.

But “we are not part of this decision-making process and they are speaking on behalf of us in respect to the biodiversity that does not belong to them”, he said. “There is no climate future and biodiversity without Indigenous peoples.”

’30×30′ initiative

The COP15 talks, which are bringing together delegates from the 196 countries that have ratified the 1992 UN Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and other stakeholders, aim to reach a framework to help guide countries on how best to protect biodiversity by the end of the decade.

One component of the proposed Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework is to protect at least 30 percent of land and sea globally through “systems of protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures” – known as the 30×30 initiative.

But while that goal has been welcomed by some as a good step forward, it also has drawn concern, with Amnesty International Secretary General Agnes Callamard, who is in Canada for COP15, saying “in its current form, it presents a grave risk to the rights of Indigenous peoples.”

“Current practice in protected areas often follows a model known as ‘fortress conservation’ which requires the complete removal of human presence from the area, usually by force, so that territory can be thrown open to tourists, conservation researchers and, in some cases, big game hunters,” Callamard said in a statement this week.

She instead urged countries to ensure that any biodiversity agreement centres around Indigenous rights, including the free, prior and informed consent of Indigenous people on projects that will affect their communities and territories, as laid out in the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Ronald Brazeau, director of natural resources at Lac-Simon, a First Nation reserve in the province of Quebec, said consent is often lacking – and a one-size-fits-all model is imposed on Indigenous communities around the world, ignoring local needs and solutions. “We have the solution, we have something to say,” Brazeau said during Friday’s news conference.

“We live off the land. We learned how to adapt to that territory, from generation to generation.”

Government approach

In Canada, “the vast majority of conservation proposals and stewardship initiatives are being led or co-led by Indigenous peoples,” explained Valerie Courtois, director of the Indigenous Leadership Initiative and a member of the Innu community of Mashteuiatsh in Quebec.

“Conservation really has to be not only about achieving numbers and lines on a map, but really about using that opportunity to rebuild the relationship between, here in Canada what we refer to as the Crown [the state], and those Indigenous nations and their governments,” Courtois told Al Jazeera in an interview.

Victoria Watson, a law reform specialist with environmental group Ecojustice who is of mixed Haudenosaunee and Scottish descent, also told Al Jazeera that “true Indigenous leadership” must be centred in any plans to protect and restore biodiversity in Canada.

That means ensuring any agreements that emerge out of COP15, as well as any national legislation on biodiversity, include mechanisms for accountability and legislative safeguards that commit governments “to respect Indigenous rights in a robust way that is aligned with self-determination”, Watson said.

These accords and laws also need to be “co-developed with Indigenous peoples”, she said. “Indigenous peoples’ laws, knowledge systems, rights and worldviews need to shape the laws that enable biodiversity protection and restoration.”

During a speech at the COP15 opening ceremony on Tuesday, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announced that his government would contribute $256m (350 million Canadian dollars) to help developing countries pursue biodiversity conservation and implement the future framework.

Trudeau also committed up to $586m (800 million Canadian dollars) to support four Indigenous-led conservation projects in Canada, covering nearly one million square kilometres (386 million square miles). “We know that protecting 30 percent of our territory requires us to form a great amount of partnerships; first and foremost, partnerships with Indigenous people who have protected these territories since time immemorial,” he said in French during a news conference this week.

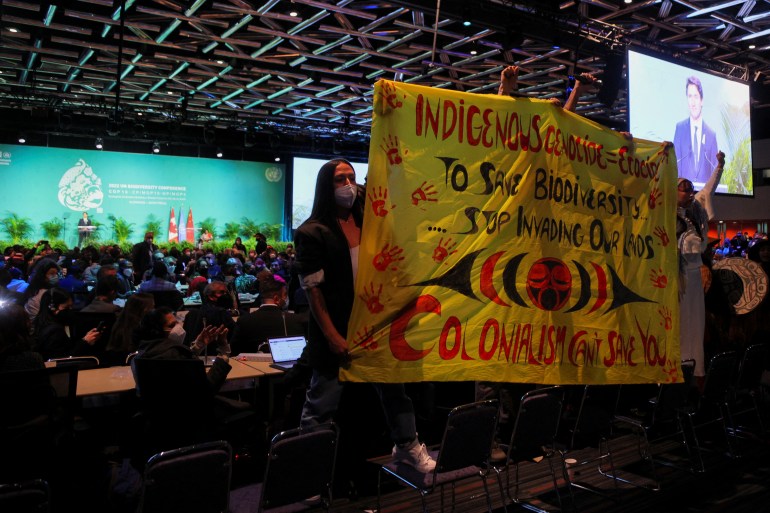

But Indigenous youth activists briefly interrupted Trudeau’s address at the opening ceremony, accusing him of failing to respect Indigenous people and laws. While he has backed international climate efforts, Trudeau has been widely criticised for supporting major development projects at home, such as oil pipelines on Canada’s west coast and to the United States.

Many of these projects have drawn staunch opposition from Indigenous communities who said the authorities never got their consent to move forward. Some Indigenous-led blockades and protests have met harsh police crackdowns.

“That was our way of showing as Indigenous people from the west coast that [Trudeau] is not following our laws, that he is not following the laws of the land, and that we cannot accept any more empty promises from Canadian politicians about our futures,” said Ta’Kaiya Blaney, a Tla-Amin Nation youth activist who interrupted the prime minister’s speech, about the COP15 protest.

“Empty promises, false solutions and fictional targets … that do nothing but pass off the burden to future generations are unacceptable,” she also said during the news conference.

‘Taking a stand’

Meanwhile, as Indigenous groups call on authorities around the world to recognise their leadership on biodiversity issues, many communities are not waiting for formal recognition to take action and protect their territories.

One such effort is the Seal River Watershed Initiative, a First Nation-led campaign that seeks to designate a pristine watershed in northern Manitoba, Canada, as an Indigenous protected area. “The narrative has always been somebody coming and telling us what we have to do. Somebody coming and moving us; somebody else telling us you can’t harvest your own food,” said Stephanie Thorassie, executive director of the initiative and member of Sayisi Dene First Nation.

In the 1950s, Canadian authorities forcibly relocated the Indigenous community from its traditional territory, ripping people from the lands upon which they had lived and hunted caribou for generations.

“As we can see from the past, from terrible histories that we live, [that narrative] has not worked for our communities and our peoples. We know now and we’re taking a stand,” Thorassie said during a panel discussion on Indigenous and local biodiversity leadership at McGill University on Tuesday.

Thorassie said efforts to protect the 50,000sq-kilometre (19,300sq-mile) watershed are “for our futures, for our cultures, for our languages” and aim to ensure that Indigenous people have “a place to be authentically ourselves”, while also contributing to the wider fight to protect the planet.

“We understand that on a global scale, this place that we’re talking about, it holds two billion tonnes of carbon,” she said. “It is literally a set of lungs for this Earth that we so desperately need to live, to survive.”