‘I’ll be sacrificed’: The lost and sold daughters of Afghanistan

Listen to this story:

Herat, Afghanistan – The last time Aalam Gul Jamshidi saw her daughter was the night the 16 year old was married off to a man more than twice her age.

Aziz Gul looked radiant in a sequinned, white wedding dress and a bright yellow headscarf, but there was fear in her otherwise solemn expressions. “If I go there, I’ll be sacrificed,” her mother remembers her daughter pleading that night last October.

Aalam Gul had a sinking feeling but convinced herself it was just nerves. Aziz Gul’s marriage had been arranged four years prior and now that the time had come, she knew it was her duty to encourage her daughter into a new family.

In Afghan culture, once a female marries, she moves in with her in-laws. Aziz Gul left her family’s home in Gozar Gah, a suburb of Herat, and moved to her new husband Musa’s home in Jawand, a rural district some 200km (124 miles) away – too far for her family to visit easily.

Five months later, the phone rang. It was Musa’s father calling to tell Aalam Gul that her daughter had been killed. Her naked body had been found in a forest just outside the village where she had lived with her in-laws. Aziz Gul had been beaten and shot four times in the back.

She was 17 years old and four months pregnant.

Aziz Gul’s family – ethnic Jamshidi Aimaq, self-described Tajik Arabs – are originally from Badghis province. They moved to Herat during the height of the conflict between the previous government and the Taliban, which retook control of the country after United States and NATO forces withdrew in August 2021.

Before the family left, when Aziz Gul was just 12, her parents agreed to marry her to Musa when she turned 16 – the minimum legal age for marriage in Afghanistan under the previous government. The Taliban has not mentioned whether that minimum age has changed. In exchange, her 26-year-old elder brother Aminullah would marry Musa’s 18-year-old niece, Shakar.

Across Afghanistan, it is common for children – particularly girls – to be married. Families arrange marriages to pay back personal debts, settle disputes, improve relations with rival families, or simply because they hope marriage will offer them protection from the worst extremes of economic hardship, and social and political upheaval.

Though child marriage is not thoroughly tracked in Afghanistan, with gaps in concrete, holistic data about the number of children affected, UNICEF has reported children being sold as young as 20 days old for future marriage, with girls disproportionately affected.

Now, amid spiralling poverty and the difficulty of finding sustainable jobs – only five percent of Afghan families have enough to eat daily, and inflation for essential household goods is at 40 percent (PDF) – even more families are struggling.

Many are making desperate decisions to survive, including selling their children – specifically young daughters – into marriage or arranging their marriages in order to receive a dowry or mahr. The dowry, paid by the groom to the bride’s family, is a traditional practice in all marriages in Afghanistan, but more families are now seeking this to help them survive difficult financial times.

‘Fits of rage’

Aalam Gul had three sons and four daughters; Aziz Gul was her second-eldest daughter. She was always close to her mother, and would typically speak to or at least message one of her family members every day.

The day after she was killed in March, her in-laws told her parents that she had run away after they were concerned when she did not return their calls. Two days later, a local farmer discovered her dead body in the forest and alerted local authorities in Jawand, who began an investigation. That same day, after villagers started talking about the incident, Musa’s father admitted to her family that she had been killed.

Soon after, Aziz Gul’s grief-stricken parents embarked on the several days’ journey to Jawand to bring her body back to Herat. “We [collected] her body [from local authorities] about three days before the month of Ramadan,” Aalam Gul says, in tears. “[The killer] just threw her body outside in a forest, as if she were not a human being. I wonder how scared she was.”

Musa and some of his relatives quickly pinned the murder on his mother, Aziz Gul’s mother-in-law. They claimed she was frustrated at her daughter-in-law for not knowing how to do housework, started beating her, and shot her in rage. But Aziz Gul’s parents suspect it was Musa. During the months the two were married, Aziz Gul and other relatives discovered that he was an opium user who would easily fall into fits of rage.

Aziz Gul’s father, Khaja Abdul Ghafor Jamshidi, says they received investigation reports from the local Taliban police authorities in Jawand. Musa and six other known criminals were questioned a few days after her body was found, but the authorities told Khaja Abdul there was not enough proof to make any arrests, and the killer’s identity remains unknown.

Eventually, the local Taliban chief in Jawand decided that this was an issue to be solved between the two families, and told Khaja Abdul that the case was closed. But it was the family’s word against Musa’s.

When Aziz Gul’s family tried to appeal to the larger, more authoritative Taliban police authorities in Herat, the case was sent back to local officials in Jawand.

According to Khaja Abdul, Musa was influential within the Jawand district. The region is considered lawless and not entirely under the control of the Taliban commanders in Kabul. Different factions operate in decentralised silos and do not necessarily communicate, follow the same rules, or want to intervene in other jurisdictions.

In Afghanistan, domestic violence cases rarely make it to the courts, including under the last government, and are often left unsettled.

‘I’m worried about my daughters’

In the Jamshidi family’s compact, mud-brick home in Gozar Gah, Khaja Abdul sits on the floor with his legs slightly crossed and his hands clasped.

“We want fairness from the Taliban, but whatever is set out in the Sharia, we will accept this as justice,” he says. “We only want to find the killer.”

He has also offered to kill his daughter’s murderer if Islamic courts decide that a blood punishment is in order – even though, for now, they are at a loss as the local police authorities have deemed the case to be closed.

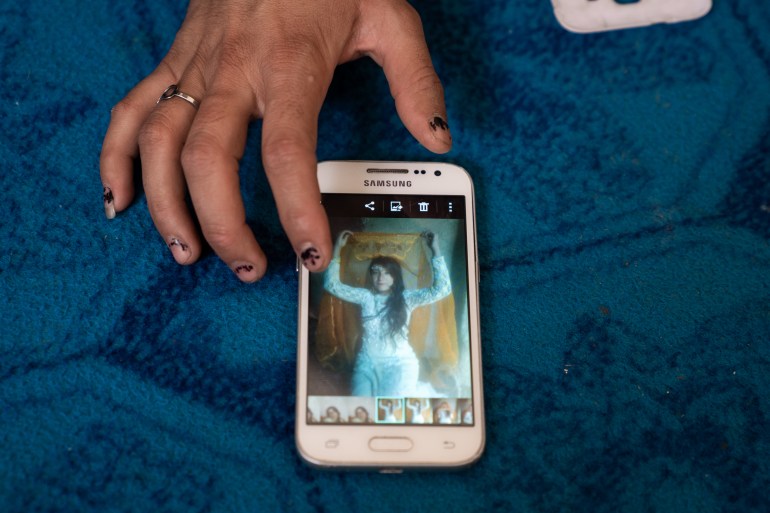

Sitting hunched over near her husband, dressed in black with a dark green hijab loosely wrapped around her head, Aalam Gul is visibly distressed. Her hands shake as she clutches a mobile phone with a picture of her deceased daughter.

Tears stream down her face as she recalls the last time they spoke. “I spoke to her four days before she died. There were obvious issues with her new family, but she didn’t go into full details about what.”

“Aziz Gul was bright and outgoing,” her mother reflects. “She studied at a madrassa for girls. She was also interested in becoming a police officer.”

“The hardest thing for her about the idea of marriage was leaving school. She loved studying.” Aalam Gul, who never went to school, says, reflecting on the idea that her daughters could live another life. “I wish they could live in a world different from the one I know. It is difficult here in Afghanistan.”

The family also needed Aziz Gul’s dowry of $3,500 to survive. Since moving to Herat, the men in the Jamshidi family have been working in construction, but the work has not been consistent, and they have faced mounting economic hardships.

Aalam Gul looks at her remaining teenage daughters sitting next to her in their small home and sighs heavily. Two of Aziz Gul’s sisters start crying when they pass around photos of her. When asked about their future, she is fearful. In their economic situation, she knows they will have to continue marrying off their daughters, but the idea of another loss is terrifying.

“I’m worried about my daughters, and I’m scared about losing others. The experience of burying a daughter is too much for any mother.”

Child selling and child marriage

In Afghanistan, women and girls have struggled for decades, with each change in government adding a new dimension to the challenges they face. During the last Taliban regime, women had little to no freedom; they were not allowed to work or go to school. Under the previous republic that took power in 2004, women were more visible in public life, but women’s rights still wavered, especially in rural areas. Domestic violence was also often justified by conservative culture.

Under the new Taliban-run Afghanistan, new rules restricting freedoms around dress, education, the right to work and freedom of movement continue to be enacted. Since the takeover last year, girls beyond the sixth grade have not been allowed to attend school. This is the age where girls, historically, are most vulnerable to being set up for marriage.

Girls as young as nine years old are being sold, and at least one or two women a day end their own lives in Afghanistan because of the current situation, Fawzia Koofi, the former deputy speaker of the Afghan parliament, told the United Nations last month.

There are concerns that the Taliban does not appear to be focused on eradicating child marriage. Many Taliban fighters have taken child brides for themselves. Taliban chief, Haibatullah Akhunzada, issued a decree barring forced marriage in December, but it did not mention a minimum age for marriage. And Sadiq Akif, the spokesperson for the Ministry of Promotion of Virtue and Prevention of Vice, was quoted earlier this year saying, “when a girl reaches puberty, she can be given to marriage”. Puberty in girls generally occurs between the ages of eight and 13.

While most countries consider 18 to be the age of maturity, many countries allow under-18s to marry in some or all circumstances.

Child marriage has always existed in Afghanistan. But, recent reports suggest an increase in child selling and marriages spurred by a deepening humanitarian crisis following the Taliban takeover. The country’s aid-dependent economy was already on edge when the Taliban seized power last August. Then the international community froze about $9bn in Afghan assets overseas and halted all funding, reluctant to work with the Taliban government. The consequences have been devastating for a country already battered by decades of war and poverty.

“Parents sometimes marry a daughter off because they cannot feed her, and they think it may be their only option to keep themselves and their other children alive,” explains Heather Barr, women’s rights associate director for Human Rights Watch. “It’s also unprecedented to have an entire country of girls shut out of high school.”

UNICEF found that the risk of child marriage is higher with the Taliban banning teenage girls from attending school. “To address child marriage, there needs to be sustained, urgent pressure from the international community on the Taliban to reopen schools. But beyond that, there needs to be a system in place, with the involvement of schools and different government agencies, that educates the society about why child marriage is harmful,” says Barr, as child brides continue to be victims of domestic violence, death by childbirth and suicide.

‘This is my family’s decision’

As the pain of Aziz Gul’s tragic end lingers with her family in Gozar Gah, at a camp for internally displaced people just 10km (six miles) away, another mother and daughter face a desperate decision.

Ten-year-old Raihana Mirzai stares timidly from behind her mother Shaima, her wide almond-shaped eyes glistening in the sunlight pouring into their small, dusty home outside Herat. She is wearing a sparkling yellow dress and a loose-fitting light violet hijab, bright red lipstick, rouge and bangles.

Raihana is dressed up for one reason only: she is engaged to be married to her 20-year-old cousin. It’s tradition to stay dressed up so that others will know that she is engaged, Shaima says.

Still, Shaima did not want to marry Raihana off so early; the arrangement is to help her older brother, Mansor. She was promised to their relatives after Mansor had a near-fatal accident a year prior and they helped pay off his hospital debts. The timeline for the marriage is unclear as the fiancé she has never met is working in Iran.

Raihana has a bright personality. The little girl’s eyes perk up when asked about her aspirations. “I like solving problems, so I want to become a doctor.” Shaima says she will have to stop going to school when she is married, as it is tradition for girls to focus on building their families instead.

Raihana understands her situation for the most part and her dreams of becoming a doctor fade away. “It’s not important if I’m happy or not. This is my family’s decision, and I want to help my brother,” she says.

Even as she holds a fussy newborn, Shaima stares at her second-eldest daughter in silence. Her eyebrows furrow as she glances between Raihana and Mansor. Mansor sits sullenly next to his little sister with his head hung low.

The country’s economic situation has exacerbated the number of families pushing their children to work. In May 2021, 13-year-old Mansor collected garbage to earn money for the family. He was clinging onto the side of the garbage truck when it turned onto a bumpy road. He lost his grip, fell onto the road and was struck by an oncoming motorcycle.

Doctors in Herat were able to revive him, but he lost his eyesight and some brain functionality. The young teenager once had stunning green eyes, but his left eye is now glazed over.

At the time of the accident, the family barely made ends meet and did not have the money to pay for Mansor’s surgery and continued treatments. Mansor was one of the family’s primary breadwinners, collecting rubbish for 100 afghanis (about $1) daily.

The ethnic Tajik family left their village in the Adraskan district four years ago amid continued fighting between the previous government and the Taliban. They relocated to Shaidan, an IDP camp that spans 3km (1.8 miles) outside of Herat to the east.

Their relatives lent them $1,100 for Mansor’s medical bills. The family has not been able to repay this loan, so the relatives asked for Raihana in exchange. According to the arrangement, the marriage would not be consummated until Raihana is 16.

The groom’s family committed to a dowry of $6,000, from which they will subtract the Mirzais’ debt. Raihana’s father, Abdulrahim, thinks it will take time for his relatives to accumulate this amount, but there is a chance his daughter could be betrothed earlier than 16.

Currently, the arrangement is strictly verbal, according to Shaima. “We have committed to this arrangement, but we told them that if we can find the money, we will pay off the debts and ask to cancel this engagement.”

Shaima is hesitant about the whole arrangement. She speaks proudly of Raihana, who is second overall in her second-grade class. Like Aalam Gul, Shaima wishes her daughter could have a different future.

‘I cannot accept selling my daughter’

The thought of losing her daughter also weighs heavily on Fatiha Mirza Zada’s mind. A year ago, her family was living in Herat city. Her husband, a security guard, was recruited by previous government forces to fight against the Taliban; he never returned. When the Taliban took over, she went twice to the city jail to see if he had been imprisoned, but there was no trace of him.

Fatiha is a seventh-grade teacher who taught girls’ classes. She goes to school daily to sign her attendance sheet but cannot teach because the Taliban have banned girls above sixth grade from attending class, and there are no other available teaching jobs in lower grades or for boys. After her husband disappeared and she stopped receiving a salary, the family fell into a spiral of poverty. They could no longer afford rent payments in the city.

The young mother started to consider the possibility of selling her older daughter. She came close. Her colleague connected her to a family who could not conceive and wanted a child of their own, but they only offered her $900. “This was not enough for the risk of leaving my daughter to strangers,” she says.

She and her two daughters – six-year-old Hosnia and four-year-old Hosaiba – relocated to a small room in a house owned by a wealthy local family, who left Afghanistan shortly after the takeover. The room is bare with a small kitchen, peeling yellow walls, a few scrunched-up pillows and a deep-red Persian carpet, but to the girls, it’s their palace and playground.

Hosnia is only a few inches taller than Hosaiba, but they have the same tufts of curly dark hair and an abundance of energy. They are spitting images of each other, especially as they both wear identical capri jeans and patterned white shirts.

They run through the rooms giggling innocently. Every time Hosnia enters the room, Fatiha stops talking and hangs her head low, as if merely speaking is an automatic betrayal. She stares at them with pain in her eyes. She doesn’t even know what she would tell Hosaiba if Hosnia disappeared. They’re best friends, but she fears they won’t survive. “Two months after the Taliban takeover, we faced many challenges. I was worried I couldn’t afford even to feed my children.”

The most common method by which a family will find out about a child for sale is through word of mouth, which has its dangers.

There are also frightening, potentially more dangerous forces at work. Smugglers and human traffickers from as far away as Pakistan and Iran are preying on desperate families willing to sell their children. Fatiha worries that her child could be sold into an abusive family.

For now, they are scraping by. The mother receives tiny sentiments of support from neighbours and colleagues. She has sold most of her possessions to afford expenses and is hopeful that schools will open so she can resume teaching.

Meanwhile, every day in Gozar Gah, the Jamshidi family walks together to visit Aziz Gul’s grave.

The story of Aalam Gul’s loss is known throughout Herat now.

Even though abuse, death and suicide are not new topics of discussion among women in Afghanistan, Fatiha feels nervous, as any mother would. She doesn’t want to be another statistic of a mother who has lost her daughter to a vicious cycle of poverty.

The young mother is afraid that her daughter will face the same fate, so she is adamant that Hosnia does not become a child bride. For now, she would rather they starve.

“I cannot accept selling my daughter, so we will try to survive for now.”