‘If I had the power I’d destroy the whole thing’: what went wrong with the ghost town of Disney-style castles?

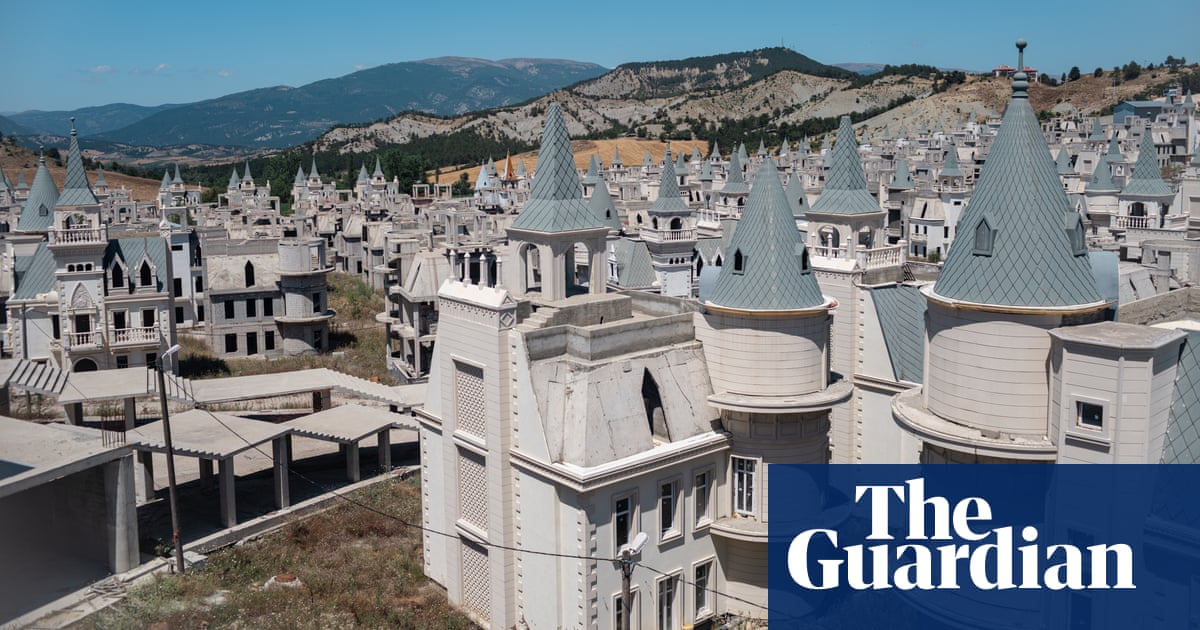

From the rooftop of the castle where I’m standing, a panorama of blue-grey turrets stretches into the distance. The effect is like staring into a kaleidoscope. It’s a fairytale sight, the intricate white-painted fronts and curved balconies resembling a collection of adult-sized doll’s houses.

The fantasy quickly falls apart, though. Many of the castles further into the complex have only bare concrete facades. In between them, spaces intended for manicured lawns have been reclaimed by wildflowers, some so tall that their petals and fronds stretch up to the first-floor balconies. An eerie silence is broken only by birdsong and the occasional passing car.

It is a warm summer day in August 2023 and there is no one here except a bored security guard and Adem Tekgöz, our tour guide to this bizarre ghost town in the Turkish countryside. Tekgöz represents the Sarot Group, the developer of this crumbling fantasy land, and his surly demeanour suggests he is not keen to show off their work to new visitors. “It gets cold in the winter, so we stopped construction. We’re preparing to restart next summer,” he says, brushing aside the question of why no work is taking place now. No matter: Tekgöz appears confident that a lick of paint and reconnecting the electricity to the wires strung between the castles will breathe life back into the project.

As we inspect the interiors, where wires dangle from bare ceilings, it’s clear that some of the rooms have water damage, presumably from the snow that blankets the surrounding valley each winter. Tekgöz’s tour also means stumbling across frequent evidence of neglect, including a bloodied bird carcass and what I hope are animal droppings near a concrete cavity in the basement of one castle. In the deserted centre of the complex, one floor of what is supposed to be a shopping mall and luxury hotel is littered with evidence of how much work is still to do: piles of abandoned filigree mouldings and unused turrets lie on the concrete.

When drone footage of the complex of 732 castles appeared online a few years ago, they quickly became a viral phenomenon: there are dozens of YouTube videos marvelling at the cluster of Disney-like chateaux. Since then, the mystery of whether they will ever be finished has only deepened.

The castles were supposed to bring a welcome injection of Gulf money to this part of Turkey. On paper, it was a tempting pitch for prospective purchasers from Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and Bahrain: a luxury development named Burj Al Babas (a nonsensical mashup of Arabic and Turkish, playing on the name of local hot springs). Each castle, when completed, was meant to have its own pipeline to the healing spring waters, feeding private indoor swimming pools. Then there was the location: a lush spot away from the intense 45C heat of Gulf summers, conveniently located between Istanbul and the capital Ankara, and only a short distance from Mudurnu’s peaceful town square and quiet streets of squat, Ottoman-era wooden houses.

Instead, since construction abruptly stopped in 2016, the project has become a bizarre white elephant. As the scandal has dragged on, it has sparked multiple lawsuits, one attempted suicide, a bitter vendetta between one contractor and the Sarot Group, and even a minor diplomatic incident between Turkey and Kuwait. The castles have become a freakish local tourist attraction, luring influencers to break into the site and film inside. Music videos have been shot there, including one for an Italian dance act featuring a motorbike and plentiful use of fire and red smoke flares.

The deserted castles have come to symbolise the financial problems and mismanagement that have dominated Turkey’s construction sector during president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s two decades in power. Companies with links to the government have cut corners with impunity – a state of affairs illustrated most dramatically by 2023’s twin earthquakes, in which cities were damaged across an area the size of Germany. The castles have also led to a major rift among the villagers in Mudurnu, between those who see the whole development as an eyesore and those who still hold out hope that the project might be good for local businesses. The only thing the hundreds of angry castle owners, local residents and the Sarot Group can agree on is that the castles aren’t going anywhere – but whether they will ever be completed remains unknown.

‘It’s a rich drama,” says Jassim Alfahhad, 55, a Kuwaiti air force colonel turned management consultant and academic, who heads a group of almost 150 disgruntled clients in Kuwait City, each of whom paid $150,000-$450,000 (£115,000-£345,000) for their identical castles. “The property owners have suffered for almost a decade.”

When we speak by phone, Alfahhad tells me he maintains two homes for his two families and sets of grandchildren (polygamy is legal in Kuwait). One he says was built to resemble a Victorian house, and the other in a more traditional Islamic architectural style. “It really looks like a castle, but a traditional Moroccan one,” he says. “I like historical architecture.”

Alfahhad had contemplated buying property in Turkey before, but the idea of a holiday home in a castle, or at least something resembling one, was just too good to ignore. After hearing about the project from a friend in the spring of 2015, he took the Sarot Group up on its offer of a free tour, and found himself enchanted. Where others dismissed them as kitsch, Alfahhad saw in the pointed turrets references to Istanbul’s Galata Tower and the Maiden’s Tower, both of which date back centuries. He remembers studying for a master’s and then a doctorate in Britain, where his weekends were spent touring stately homes and castles across Scotland and Wales. Even though the chateaux were close together, he felt they were perfect for someone like him who longed for the isolation of the temperate Turkish countryside.

Back in Kuwait, he visited the Sarot Group’s sales office and met co-director Bülent Yılmaz, who helped Alfahhad pick the idea spot on the hillside, one he said would be away from the bustle of the shopping mall and supermarket. His castle cost $290,000. Alfahhad paid the first of several instalments, and began the wait.

“That’s how the tragedy starts,” he says. “The contract stated that by 31 December 2018 the project would be finished and we would be able to receive our villas. Of course, that did not happen.” The contract also stated that any delay to the castles’ delivery date would incur a fine of $2,000 a month, payable to each buyer.

Mudurnu is an unlikely location for bold feats of architecture. The townspeople are proud of the 130-year-old wooden clock tower, built in the same style as the Ottoman-era buildings that housed traders travelling the Silk Road. With its population of 5,500, Mudurnu is the kind of place where residents know their neighbours intimately. Locals here have taken to referring to Burj Al Babas as “the Dracula castles”.

“This is a town where people don’t lock their doors. We trust one another,” says Mehmet Cantürk, sitting under an awning in the garden of his 200-year-old wooden home. Cantürk is a softly spoken, white-haired environmentalist who can name every species of plant in his garden and the surrounding area. Mudurnu, he explains, is a place that’s all about respect for “traditional values, and that means opposing consumerism”.

“If I had the power, I would completely destroy the whole thing,” he says of the development. “I would simply grant nature the power to reclaim the entire area.”

Cantürk first heard about the project in 2011, when he sat on the local council. Among his concerns are the way the construction clashes with local traditional architecture, the abundant use of concrete, and assorted prejudices about an influx of Gulf visitors not understanding Mudurnu. Then there is his objection to the privatisation of the Babas hot springs underneath the site to feed the castles’ swimming pools. The Sarot Group acquired the right to extract the spring water from the land, a resource Cantürk says should be public.

He believes that plenty of others share his views, even if they have been less willing to complain to the local authorities. For the residents of Mudurnu, the project steamrolled from a slideshow to a construction site with an eerie sense of inevitability. He adds ruefully: “When there’s one person who objects, it doesn’t have a lot of impact on the municipality.”

Mudurnu, like much of Turkey, is trying to weather high unemployment and an economic crisis that in recent years has seen Erdoğan turn to the Gulf, notably the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia, for a bailout. The country is dotted with a string of failed efforts to attract Gulf money, including an abandoned dinosaur park in Ankara that cost $801m, according to the capital’s mayor, who has criticised his predecessor for greenlighting it. None of this dissuaded former Mudurnu mayor Mehmet İnegöl from granting the Sarot Group planning permission for 80 castles in 2011. Four years later, an adjacent plot of land was rezoned to become part of Mudurnu, and İnegöl gave Sarot permission to build the rest of the 732 castles, with half intended for wealthy Gulf buyers and the remainder marketed as timeshares for domestic tourists. He says his motivation was the promise of jobs – but some also point to İnegöl’s relationship with Mehmet Yerdelen and the Sarot Group.

Since then, the Sarot Group’s timeshare empire has spread across the verdant hills outside Mudurnu. There’s the Sarot Thermal Park up a winding path on a hillside, which boasts spa facilities, healing pools and treatment rooms. Next door is the Sarot Thermal Palace with its golden rooftop, a cavernous atrium, timeshare hotel rooms and rows of pink plastic cherry blossom trees near swimming pools that when we visit are bustling with visiting families. The hotel’s pillars and mouldings appear to be carved from crimson marble, but a light touch reveals some far cheaper material and a hollow interior. Adjoining this is a cluster of squat timeshare apartments, the Sarot Thermal Valley Holiday Village.

One shop owner from Mudurnu cautiously describes how she bought a timeshare there, but was burnt when she bought a second in a nearby valley that was never delivered. This was the Sarot Village – a group of buildings shaped like giant grey birdhouses, all made entirely from concrete, including the roofing. The unconventional design choice is explained by the Sarot Group’s in-house concrete company, which seemingly churned out every part of the strange buildings around the same time as the castles. Now, their deserted rows are lined with tall grass, making this an ideal setting for a horror film. The shop owner refuses to give her name, saying she was too scared to take legal action at the time, and even now fears reprisals from the Sarot Group or those connected to them. “I feel we were scammed,” she says.

The Yerdelen family, who primarily control the company, also have deep ties to the Saadet party, a conservative Islamist group that splintered from the same parent organisation as Erdoğan’s Justice and Development party (AKP). At least two members, including Mehmet Yerdelen, have held local office for the party in Istanbul. The wedding of Yerdelen’s son Enes was attended by an array of stars from Turkey’s conservative Islamist movement, and included a fiery speech from the son of the late prime minister Necmettin Erbakan, godfather of Turkish Islamist politics, and Erdoğan’s mentor.

Yerdelen insists that the Sarot Group does not “have a political identity” and that purchasers’ fears about reprisals are unfounded. He maintains that approval for the Mudurnu project was granted at a level above İnegöl, downplaying the former mayor’s role in approving the project. He also says his friendship with İnegöl pre-dates any thoughts of the castles, describing him as “a friend whose only purpose is to serve the people of Mudurnu”.

after newsletter promotion

İnegöl lost his position as mayor in 2019. He says the Sarot Group has done nothing illegal, and defends what he calls his “acquaintance” with Yerdelen. “Politicians and investors are always close,” he says. Even now, the former mayor describes the castles as an economic boon to the town just waiting to happen. “Unhappy people could never properly understand the development,” he says. He claims its detractors will someday be the “first to bring their children to be employed” there.

Yerdelen blames Turkey’s economic crisis for the delay in construction, along with buyers failing to make payments – a claim contradicted by Alfahhad and his group in Kuwait. He insists the Sarot Group will someday resume building. Mudurnu’s newly elected mayor, Doğan Onurlu, says: “It’s a private company, so we’re not responsible. It would be good to finish the construction. That’s all we’re going to say,” before hanging up the phone.

Construction of the castles ran into problems not long after the Sarot Group broke ground in Burj Al Babas. On arriving at the site in 2014, contractor Çapan Demircan turned whistleblower and filed a complaint with local prosecutors, claiming the construction company was breaching environmental laws by dumping rubble on the pines that cover the hillside.

When we meet in the bright conference room at the offices of a local paper near Demircan’s home in Istanbul, he is bursting to talk about what has become a years-long obsession. Demircan has complained persistently to the authorities about the castle project, badgering any official he could find in Mudurnu or the surrounding Bolu provincial government. To hear him tell it, no one was willing to listen. “I was seen as a troublemaker just creating problems out of nothing,” he says.

In February 2015, a group of workers began to protest over unpaid wages at the construction site. According to local media, one of them climbed to the top of a tower that housed the Sarot Group’s on-site concrete manufacturing facility, threatening to jump to his death if he wasn’t paid. A photo that ran in many Mudurnu papers shows him gripping the railing on the roof of the building. His death, they said, was ultimately prevented by local firefighters who arrived at the scene.

Demircan says he pulled out of the project not long afterwards, citing myriad concerns about how it was run, and by then he says the Sarot Group owed him almost $700,000 in unpaid wages. He describes how, after his initial complaint about environmental violations, he and Yerdelen attempted to sue one another for defamation, but their legal battles eventually fizzled out.

His eventual showdown with Yerdelen took place at the Sarot Group’s offices in Mudurnu, in the summer of 2016. Demircan says he arrived at the glass-fronted building to see Yerdelen’s sleek black four-wheel-drive parked outside. Demircan tells me he didn’t plan on getting violent, but describes a heated exchange with a man he says he recognised as an employee of Sarot, who moved to attack him. Demircan says he hit back, striking the man in the nose and mouth, after which Yerdelen abruptly sped off in his car. (Yerdelen denies the incident took place, or that Demircan was owed money.) The former contractor says he received a quarter of his fees, but others weren’t so lucky.

Demircan says he tracked down İnegöl in 2018, at a street festival in Bolu, the provincial capital. Again, Demircan claims he threw a punch, before security and a local official intervened. İnegöl says he only found out about this incident later from his security team. “If he made such an attempt, I didn’t notice it,” he says. Demircan says he then drove from the festival to Mudurnu, where he began to patrol in front of İnegöl’s house. When the local police got involved, along with the town prosecutor, Demircan abandoned his vendetta and left town. He hasn’t returned to Mudurnu since, and has dropped his lawsuit alleging environmental damage and other complaints against the company.

By late 2016, it had started to become clear to Alfahhad, the Kuwaiti buyer, that construction work on the castles wasn’t happening on schedule. The Sarot Group initially blamed the cold winter weather, then the after-effects of a failed military coup, which shook Turkey that July. Cantürk and others in Mudurnu began to notice contractors were no longer showing up at the site, and suspected complaints about pay were to blame.

As the months wore on, the Kuwaiti buyers began discussing other options. Some attempted to sue the Sarot Group, but the cases stalled. Alfahhad claims some members even attempted to introduce Yerdelen’s co-director Bülent Yılmaz to wealthy Kuwaiti investors who offered to take over the project, but that Yılmaz shrugged them off. Yılmaz declined to answer questions, claiming he left the Sarot Group in 2017, although records show he remained on its board until last year.

The Sarot Group entered bankruptcy proceedings in 2018, with Yerdelen blaming the buyers for not making payments on time. Alfahhad shows me a document from the Sarot Group to prove that he has paid in full, and says Yerdelen’s comments only irked them more. Sure enough, an Istanbul bankruptcy court ruled that the Sarot Group was comfortably in credit in late 2022.

By this time Alfahhad and his group were despairing of the Turkish judicial system, believing that only diplomatic intervention could save their castles. He began using his connections as a former Kuwaiti prime ministerial adviser, calling the Kuwaiti foreign ministry and setting up a meeting with the Turkish ambassador to Kuwait. He also flew to Ankara several times to meet the Kuwaiti ambassador there, reassured by his pledge to treat the castles “like an emergency” and raise the issue at the highest echelons of the Turkish state.

The issue appeared deadlocked until May this year, when the emir of Kuwait, Sheikh Meshal al-Ahmad al-Jaber al-Sabah, made a state visit to Ankara. Arriving in sunglasses and sweeping gold-fringed robes to a full military welcome, the emir met Erdoğan, and the two leaders were pictured walking down a pale blue carpet to the presidential palace, their hands clasped. It was a welcome development for Alfahhad and the other buyers, who understood that the emir and Erdoğan found time to discuss the hundreds of unfinished concrete castles. The Turkish presidency has declined to comment.

Whatever took place behind the ornate doors of the presidential palace, the emir’s visit does seem to have turned things around for Burj Al Babas. Or, in the words of lawyer Selim Sarıibrahimoğlu, who has advised the castle owners, it has “pumped some warm blood into this issue”. Now an Istanbul court that examines financial and organised crimes has taken up the case, and is combing through the Sarot Group’s finances, as prosecutors accuse them of defrauding investors and using Burj Al Babas as a front company for suspicious transactions; Yerdelen says there is no truth to allegations of money laundering. All 14 of the companies run by Yerdelen and the Sarot Group, including those overseeing construction of the castles, have been entrusted to a Turkish state fund partially controlled by Erdoğan’s office and intended to rectify the finances of troubled businesses.

Sarıibrahimoğlu points to a puzzle that has hung over the project for years: Yerdelen and the Sarot Group had millions of dollars in sales, more than enough to finish building the castles. Surely it would have been easier just to finish the project rather than endure these years of trouble? “It really is an odd thing,” he says. “I don’t know why they put themselves in this situation. But these things can always be solved at a political level. We are happy now that everything is under the control of the Turkish state.”

Others – like political consultant Selim Sazak – contend that the trickle-down corruption of the Turkish state under Erdoğan is what allowed the castles to be built in the first place.

“These people were powerful enough, socially and maybe politically, to get the construction permits they got and to market them to the Gulf,” he says of the Sarot Group. The castles, he adds, are “a monstrosity”, a project that shows how even those with political connections far from the presidential palace “can end up doing something this brazen”.

As the court proceedings drag on, the castles remain untouched. The weeds and wildflowers have grown taller, but the project remains frozen in time. Yerdelen says he believes “with all my heart” that his company will one day not only finish building the castles, but throw a grand opening party to celebrate. He dismisses state control of his companies as something “temporary”, adding: “We plan to continue construction where we left off.”

Alfahhad also believes that he and the other buyers will eventually get their castles on the hillside, but not from the Sarot Group. Then there’s the small matter of the late fees that the Sarot Group owe each buyer, which he says they intend to claim. The company currently owes him almost $150,000, half of what he paid for his castle; Yerdelen says buyers should direct their demands about fees to the Turkish state fund.

“We remain optimistic that this will end soon – but of course it won’t be like receiving one five or six years ago,” says Alfahhad. “Some of the other buyers lost loved ones – they died before this project was finished. They just wanted to go and sit in their castles.”

/cloudfront-us-east-2.images.arcpublishing.com/reuters/VRBH7MMONVJIJGNAMNLTGYXL2Y.jpg)