‘I wanted vengeance’: Tibet’s last resistance fighter

New York, United States – More than 70 years after China invaded Tibet, Tenzin Tsultrim can still recall events as if they were yesterday.

A teenager at the time, Tsultrim was in training as a novice monk in eastern Tibet and remembers bombs from the planes of China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) air force falling on the monastery. He was too young to fight but the older monks all took up arms.

Now 87, Tsultrim casts his mind back to those days long ago and clutches his prayer beads.

His eyes narrow.

“That was when I first got the idea that I needed to fight back once I could,” Tsultrim told Al Jazeera from New York where he has lived since 1997.

Eventually, Tsultrim and tens of thousands of other Khampas, from Tibet’s eastern Kham region, fled to Lhasa in central Tibet, which remained relatively calm.

There, the Dalai Lama entered into an agreement with the Chinese communist government in a bid to retain his authority. But the appeasement did not last and, after a 1959 uprising was brutally suppressed, Tibetans mounted a years-long resistance against communist rule.

Tsultrim eventually joined the rebellion and is now known as the last survivor among what was a legion of resistance fighters.

“It is extremely sad as most of them have been forgotten by the Tibetans today; there’s no remembrance,” he said. “But I keep them in my prayers every day.”

Clandestine weapons drops

The story of Tibetan resistance against Chinese rule, backed by covert military aid from the United States, is a little-discussed early chapter of the Cold War in Asia. The operation, which lasted from 1957 until 1973, was enabled – but ultimately undone – by the ever-shifting alliance between the powers that surround Tibet – namely China, India and Nepal.

Tibet was communist China’s first conquest. Beijing now has its sights set on Taiwan, seeing the self-governing island as the last piece of territory to be brought into Beijing’s embrace. The forgotten history of how Tibetans fought against China’s incursion is more relevant now than ever, and it is a history being resurrected by the Tibetans themselves.

Tsultrim was from a well-to-do merchant family that was friendly with Andrugtsang Gompo Tashi, a widely-respected Khampa trader who began to pour his fortune into fighting the Chinese. By 1957, Gompo Tashi was assembling a militia – called “Chushi Gangdrug” in Tibetan – and Tsultrim was old enough to answer the call to arms.

“I decided then I had to do something,” he told Al Jazeera in Tibetan.

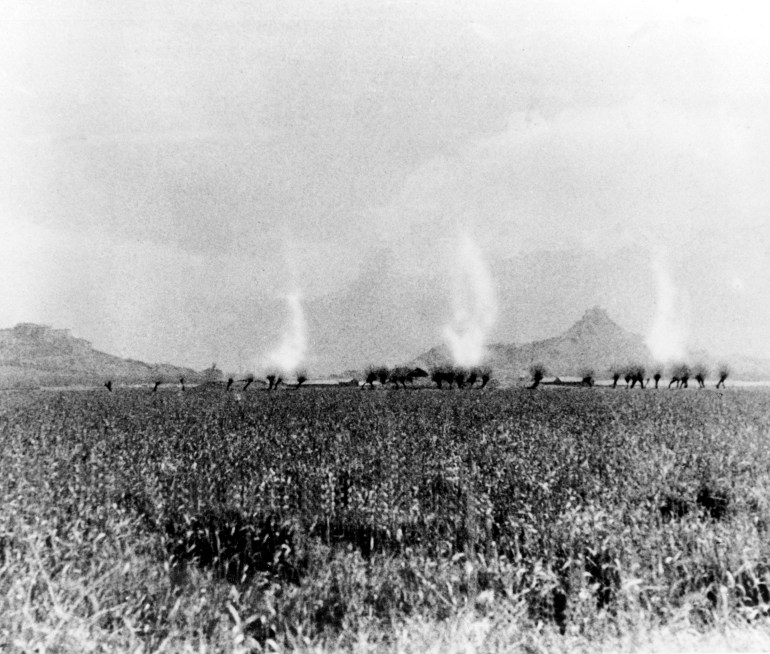

The newly formed militia set up a base in a part of southern Tibet bordering India where there were few Chinese troops. In July 1958, it received its first airdrop of ammunitions and automatic rifles from the US and in eight months, the resistance’s presence proved crucial to carving out a safe route for the Dalai Lama to flee Tibet for India.

Not long after that, however, after one too many ambushes by the PLA, the resistance fighters were forced to decamp, ultimately regrouping in an isolated mountainous Tibetan enclave in Nepal called Mustang, which juts into Tibet.

In addition to airdrops, agents from the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) were training the Tibetans in guerrilla tactics. By 1962, Tsultrim, then 26, had been selected for boot camps in the mountainous US state of Colorado where the altitude approximates Tibet’s.

Every trainee was given an English name and Tsultrim became known as Clyde. In two years at the camps, he was schooled in skills such as pyrotechnics, Morse Code, map reading and parachuting. He said because of his performance in wilderness survival, he was also plucked for leadership training for his unit.

Once their training was complete, he and 15 other armed rebels were flown back to India and exfiltrated into Tibet overland – the last unit to parachute in had all perished. Tsultrim recalls dressing in rags to disguise himself as a beggar on his frequent clandestine trips to his homeland.

“I wanted to kill the Chinese. I wanted vengeance,” Tsultrim said. “I was prepared to be killed.”

China’s secrets

Much as the Tibetans were spoiling for combat, the Americans were singularly focused on gathering intelligence. A major success came in 1961 in a blood-stained, bullet-battered pouch from a PLA commander holding a cache of 1,600 classified Chinese documents. They detailed the famines, the failure of the Great Leap Forward and the internal strife within the military and the Chinese Communist Party at a time when information on China was almost non-existent.

It was touted as “the best intelligence coup since the Korean War (1950-53)”, according to Orphans of the Cold War: America and the Tibetan Struggle for Survival by ex-CIA officer John Kenneth Knaus.

Even so, Tsultrim’s group turned out to be the last trainees under American tutelage. By 1965, the US was cutting funding for the clandestine operation. The growing rift between China and the then-Soviet Union had created an opening for an eventual Sino-US rapprochement, making the covert mission at once untenable and unnecessary. All told, several hundred fighters had been trained.

Coming of age in Darjeeling, India, the political heart of the Tibetan exile community in the 1960s, and imbibing Ernest Hemingway’s dispatches from the Spanish Civil War, Jamyang Norbu grew up itching to join the resistance. With his English writing skills more in demand than his fighting spirit, Norbu was deployed to Dharamsala to assist in translation and intelligence.

By 1970, he was deployed to Mustang – just in time to bear witness to the demise of the resistance.

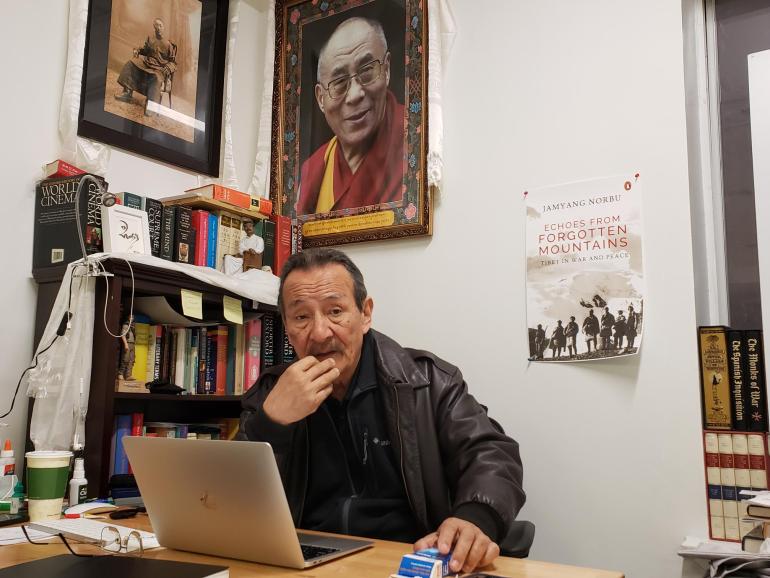

“It was easy to see it was only a matter of time that the thing would fail,” said Norbu, 74, half a century later in a New York City basement office that he has built into a research outfit on Tibetan culture and politics called High Asia Research Center and Library.

The end came in 1973, when the new Nepali king sought a closer alliance with, and substantial aid from, Beijing. The Tibetan fighters in the Mustang base were ordered by the Nepalese to surrender their arms and disband.

While Dharamsala has remained a refuge for the exiled fighters, the existence of the militia was deemed an embarrassment to the non-violence policy the Dalai Lama had come to espouse and embody. At the same time, the growing notoriety of CIA operations meant any mention of past association would be a liability to the Tibetans’ cause.

Writing as a weapon

As Norbu retreated from Nepal, he started gathering material and doing interviews with his fellow fighters and other exiles. His decades of research culminated in Echoes from Forgotten Mountains: Tibet in War and Peace, a book of more than 900 pages that will be published in English this month by India Viking, an imprint of Penguin Random House.

“Without the resistance, there would be no exile community,” said Carole McGranahan, an anthropologist and historian on contemporary Tibet at the University of Colorado Boulder in the US and author of Arrested Histories: Tibet, the CIA, and Histories of a Forgotten War. “This is the story he’s been trying to tell for a long time, even when the resistance still has a troubled place in Tibetan history.”

Even so, this history recently won the official nod – in the form of a permanent exhibit in the Tibet Museum, opened in February 2022 by the Central Tibetan Administration, the Tibetan government-in-exile in Dharamsala.

As much a fighter as ever, Norbu now puts his faith in the might of the written word.

“For me, writing is like a weapon. I’m butting heads with the Chinese regime,” said Norbu. “It’s an uphill battle.”