How the October War changed the world

It was supposed to be impenetrable, the steep, 21-metre (70-foot) wall of sand dotted with heavily armed strongholds – attempting to breach it, a suicide mission.

Or so the Israelis thought.

They calculated that the Bar Lev Line, a 150km (93-mile) sand embankment that stretched from the Gulf of Suez to the Mediterranean Sea, would take 12 hours to pulverise with explosives – enough time to send reinforcements.

But when the Egyptians came on October 6, 1973, they pounded it down in just three hours, using water pumps.

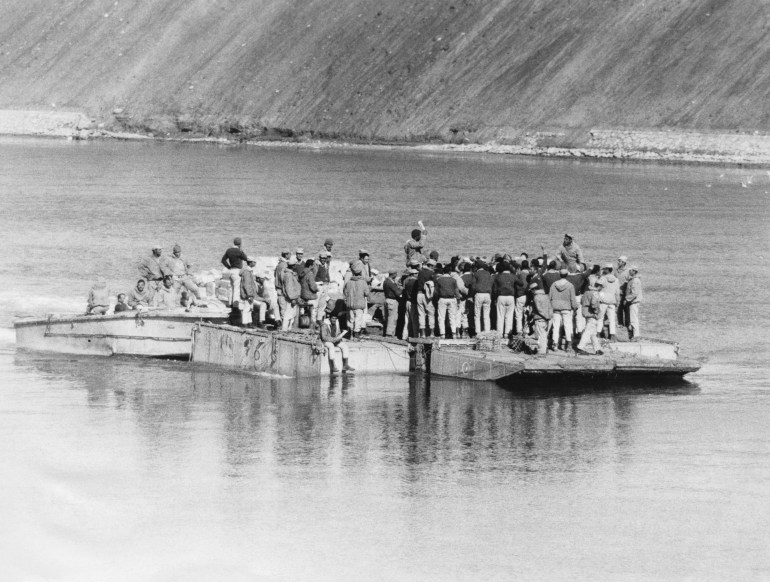

“A few minutes after 1420 hours, as the canisters began to belch clouds of covering smoke, our first assault wave was paddling furiously across the canal, their strokes falling into the rhythm of their chant, ‘Allahu Akbar…Allahu Akbar…’,” wrote Lieutenant General Saad el-Shazly, an Egyptian military commander at that time, in his 1980 account of the events titled, The Crossing of the Suez.

“[Our] aircraft skimmed low over the canal, their shadows flicking across enemy lines as they headed deep into the Sinai,” el Shazly continued. “For the fourth time in my career, we were at war with Israel.”

The attack was timed with another in the north, a battalion of Syrian forces that launched an assault to take back the Golan Heights.

Israeli forces were aghast. Yom Kippur was being observed in the Jewish state and Ramadan elsewhere in the Middle East, but that did not deter the start of Operation Badr.

Riding high on the victory of capturing territory four times its size in the 1967 Arab-Israeli war, Israel never anticipated an attack like this.

This first battle spiralled into the bloody 19-day war known by several names: the October War, the Yom Kippur War, the Ramadan War, or the 1973 Arab-Israeli War.

Fifty years later, it is clear the war changed not just the region and the future of Arab-Israeli relations, but also the world, as it rocked the orbit of the Cold War, altering the US’s approach to the Middle East.

‘Egypt’s finest hour’

Tewfick Aclimandos was just 14 years old when the war began but he has significant, if vague, recollections of it.

Neither a success nor a failure, it was still “Egypt’s finest hour”, Aclimandos, director of the European studies unit at the Egyptian Center for Strategic Studies and professor at the University of Cairo, told Al Jazeera.

Taking back the Sinai Peninsula from Israel was a victory that cemented the Egyptian army’s might under the leadership of President Anwar Sadat, he said. It gave legitimacy to every successor of Sadat’s who took part in the war effort, he added.

“We are the founding fathers, we are the protectors of Egypt,” was the army’s messaging after taking back the Sinai, Aclimandos recalled.

It is no wonder, then, that in the years following it, the anniversary of the war is celebrated widely, from free entry to military museums on October 6 to ceremonies and parades.

Just as focused as Cairo was on taking back Sinai, so too was Damascus on the Golan Heights. Israel had captured both in the 1967 war, alongside occupying what remained of Palestine.

Conditions were ripe for the October War in the Arab mind: An Arab front heading into battle to avenge the suffering of Palestinians and to take back their own territories.

However, the events of the October War did not advance the Palestinian cause. According to Sami Hamdi, the managing director at International Interest, a political risk firm focusing on the Middle East, it was, in fact, “a resounding failure” in that regard.

“Arab states restoring justice for Palestine was completely blown apart by the October War,” he told Al Jazeera.

While it was believed that the two most powerful armies in the region at the time would be able to push back against the Israeli occupation, the war instead ended with Egypt normalising relations with Israel, explained Hamdi.

Cairo and Damascus waged the war for their self-interests and the Palestinian cause was secondary, he argued.

Arab leadership in the region, as a result, was completely “broken” by the events of the war, he said.

A united Arab front, splintered

The war demonstrated, however, that a united Arab front could be leveraged to spur action on the world stage.

When the tide of war turned in favour of Israel and fighting came to an impasse 12 days into the conflict, the Arab oil-producing countries, under the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), decided to reduce their oil production by 5 percent.

The states declared they would maintain the same rate of reduction each month until Israeli forces withdrew from Arab territories occupied in 1967, and the rights of Palestinians were restored. They also enforced an embargo on the US, suspending oil supply.

These actions had oil prices soaring – and affected the trajectory of the Cold War.

The Soviets had been supplying the Arab states with weapons, while the US backed Israel, but the embargo had the US scrambling for solutions to the conflict.

“This was also an opportunity to push away [the Soviets],” Yossi Mekelberg, an expert on Israel at Chatham House, told Al Jazeera.

Thus, Henry Kissinger swooped in, the former US national security adviser shuttling from Cairo to Damascus, to Tel Aviv in an attempt to forge Arab-Israeli peace.

His “shuttle diplomacy” – as his scuttling peacemaking was termed – worked, as it brought a ceasefire that would end the war, said Mekelberg.

Nimrod Goren, senior fellow for Israeli affairs at the Middle East Institute, agreed, saying the events were momentous in shifting the world from an era of war to an era of diplomacy,

“It was a watershed moment,” he told Al Jazeera.

But the Kissinger-fronted US diplomacy with individual countries was exactly what splintered a united Arab front, said Hamdi.

For example, Hamdi said, Kissinger probably told the Egyptians, “I can convince the Israelis to give up Sinai”.

As such, he made a concerted effort to build relations based on individual interests that ultimately superseded pan-Arab ties, the analyst explained.

This would be reflected in the coming years, particularly in the Gulf War of 1990, said Hamdi, when Iraq invaded Kuwait and a US-led coalition, which included other Arab states, came to Kuwait’s defence.

The trek towards Arab-Israeli peace

Kissinger’s shuttle diplomacy eventually cut Egypt off from the Arab fold when Cairo normalised relations with Israel.

In the aftermath of the war, Sadat tried to break the deadlock of Arab-Israeli peace agreements, said Mekelberg.

In 1977, the former Egyptian president appeared in Jerusalem to give a speech on peace to the Israeli parliament, the first Arab leader to visit Israel.

That was followed by the signing of the Camp David Accords in 1979, at the behest of US President Jimmy Carter, who invited Sadat and then-Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin to a retreat in Washington.

The accords were the basis for the Egyptian-Israeli peace treaty – which shook Egypt loose from the Arab League fold.

“Egypt had sold out the Palestinians” was the common sentiment, said Hamdi.

Sadat’s position, meanwhile, was that Egypt had done its best to fight two wars for the Palestinian cause and could not be expected to deliver justice alone, the analyst said.

The peace treaty, therefore, was to get Israel off its back, while its leaders and populace still harboured deep resentment towards the Israeli occupation, Hamdi explained.

Israel, for its part, was also invested in patching things up with Cairo – its biggest lesson from the war was the necessity of peace with its neighbours, said Goren.

The 1967 war had bloated Israel’s confidence in its military might, and the recently formed state was convinced it was invincible, said Mekelberg. The October War changed that perception quickly.

There has been little success in Arab-Israeli peace in the 50 years since the war, however, the Israeli-Egypt peace treaty at least remains intact for the most part, Goren said.

For the Egyptian commander on the war’s front lines, the war and its ensuing covenants were justified.

“One may be aggressive; one may have risked one’s life for one’s country. But why should that predispose one to gamble with the future of the armed forces and the fate of one’s country?” el-Shazly wrote.