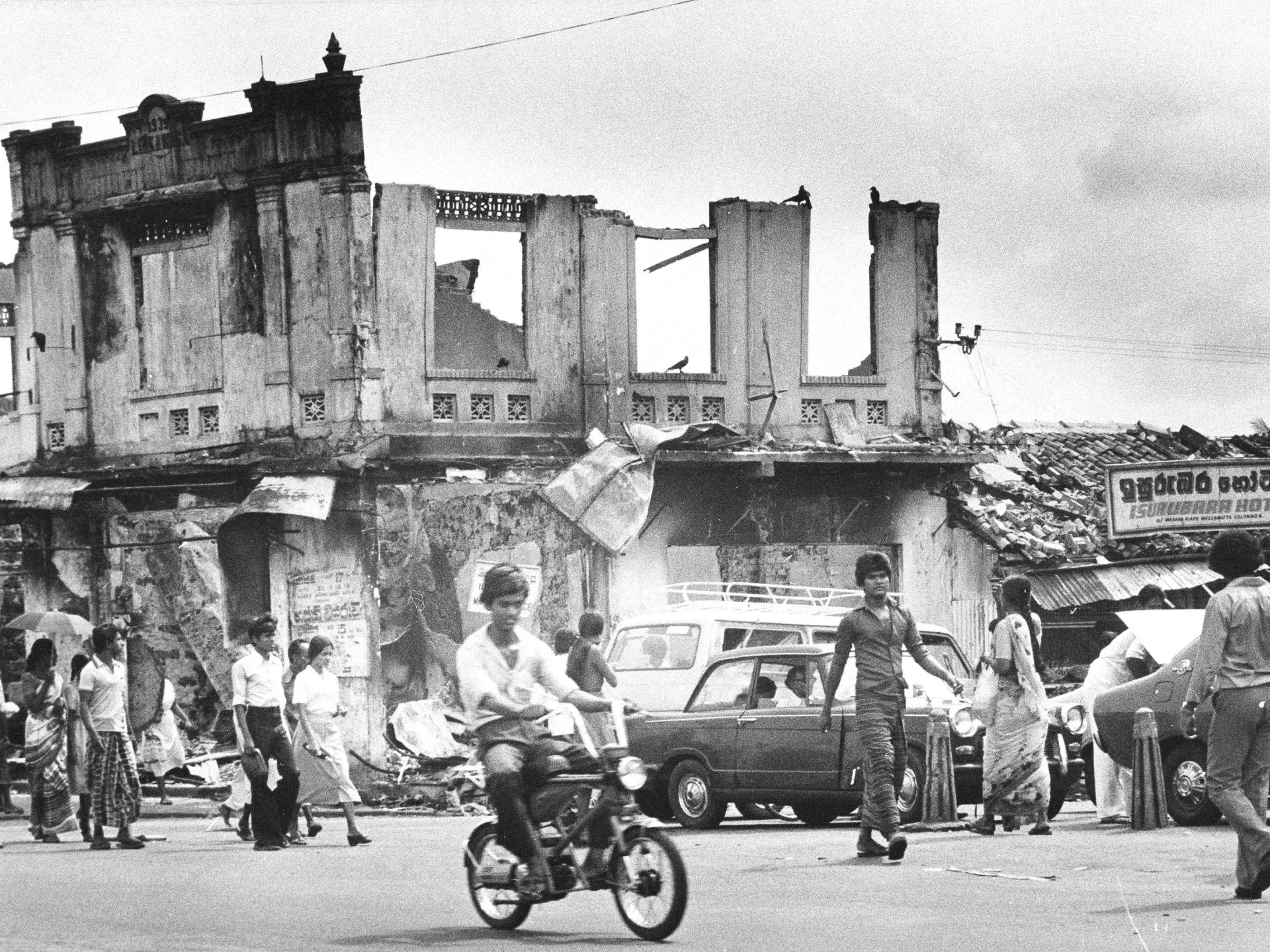

For Sri Lankan Tamils, the Black July pogroms live on, 40 years later

The Tamil community from Sri Lanka commemorates the 40th anniversary of Black July this week.

The anti-Tamil pogroms which occurred throughout the island in July 1983 were the culmination of years of systemic violence and discrimination.

Politicians, including then-president JR Jayewardene, the uncle of current President Ranil Wickremesinghe, chose to fan the flames of ethnic violence instead of addressing the legitimate concerns of the Tamil people. Weeks before Black July, Jayewardene stated in an interview with the Daily Telegraph in the United Kingdom: “Really, if I starve the Tamil people out, the Sinhala people will be happy.”

During the pogrom, Sinhalese mobs killed several hundred Tamils, according to government numbers, though activists have long insisted that the evidence suggests the true death toll was in the thousands. The mobs also destroyed Tamil businesses and displaced tens of thousands of Tamils. The violence was targeted and intentional, while police and government officials either failed to stop the violence or actively encouraged it. This has led to allegations that the events of Black July represent genocide.

The pogroms did not occur spontaneously, whipped up in a flash of ethnic tension and violence. Black July occurred after years of similar anti-Tamil pogroms in 1956, 1977, after the burning of the Jaffna Library in 1981 – destroying more than 95,000 historical Tamil texts and manuscripts – and after months of violence from May to July in 1983.

The 1977 parliamentary election was a tipping point. After years of nonviolent protest by Tamil politicians and civil society, the Tamil United Liberation Front – a coalition of Tamil parties – won a resounding electoral victory in the country’s northern and eastern provinces on the political promise of creating an independent Tamil state.

Yet, instead of trying to address the concerns driving that sentiment, the Sri Lankan government responded with more state violence. By 1983, tired of what they deemed the futility of non-violent protests, nascent armed Tamil groups were beginning to engage in attacks against the state.

Days after the horrific anti-Tamil violence of Black July, on August 4, 1983, the Sri Lankan government, instead of passing constitutional changes to protect Tamils, passed the 6th amendment to Sri Lanka’s constitution which criminalised the advocacy of a separate state.

This amendment in combination with the draconian Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA), which is still in effect, continues to be used as a tool of violence to arbitrarily detain and terrorise Tamils. The PTA has been used to target members of the Muslim community as well, especially in recent years.

The political underpinnings of Black July still characterise the state today. The hardening of the state’s ethnocratic foundation on the basis of Sinhala-Buddhist nationalism set the stage for the violence which would eventually lead to a 30-year-long armed conflict in Sri Lanka during which the state has been accused of war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide.

In the 40 years since Black July, there has been a striking absence of accountability. This has allowed an environment of impunity to flourish and thrive, emboldening individuals who stand credibly accused of perpetrating or abetting crimes throughout the armed conflict to assume prominent roles as political, economic, and military leaders.

Fifteen years following the end of the armed conflict, the echoes of Black July still resonate.

The northeast of the island, where most Tamils live, remains developmentally and economically deprived, their plight exacerbated by the significant presence of the Sinhalese-dominated military.

The ethno-nationalist ideology continues to echo through the corridors of power, shaping policies and governance in ways that further marginalise the Tamil people. As long as this ideology remains interwoven with governance, the country cannot claim true progress or unity.

The lack of political will of successive Sri Lankan governments to engage their Sinhalese electorate on these issues has only further entrenched Sinhala-Buddhist nationalism. In the years after Black July, the government established the Presidential Truth Commission on Ethnic Violence in 2001, mandated to investigate the ethnic violence against the Tamils that took place between 1981 and 1984. However, this commission, like other truth commissions established in Sri Lanka, failed to bring any semblance of justice or accountability for the victims.

Since the 1970s, Sri Lanka has set up more than 15 such commissions. But their limited mandates, lack of transparency and lack of political will have contributed to a justified mistrust of domestic-led mechanisms, perpetuating the sense of injustice and marginalisation experienced by the Tamil people, and leading to demands for international investigations.

The government is now touting a new initiative through a proposed National Unity and Reconciliation Commission. This has rightly been called out by various Tamil civil society organisations as being yet another disingenuous means for the Sri Lankan government to pretend to move forward on ‘reconciliation’ without addressing the lack of accountability and acknowledging the root causes of Tamil disillusionment.

Tamil calls for internationalised justice mechanisms should be heeded, and Tamils must be able to fully exercise their political demands for self-determination. The twin demands of accountability and a sustainable political solution have remained unaddressed since Black July, and it is only by meaningfully engaging with both of these issues that there is the possibility for change in Sri Lanka.

As Tamils in the northeast continue to mobilise and demand their grievances be addressed, now more than ever, sustained international pressure on Sri Lanka’s government to address Tamil concerns will be crucial for any semblance of a brighter future.

The views expressed in this article are the authors’ own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.