EU’s slow move to common asylum policy ‘fails to prevent deaths’

Athens, Greece – A recent breakthrough on a common asylum policy in the European Union does little to prevent the deaths of asylum seekers crossing the Mediterranean Sea in perilously overfilled vessels, migration experts have told Al Jazeera.

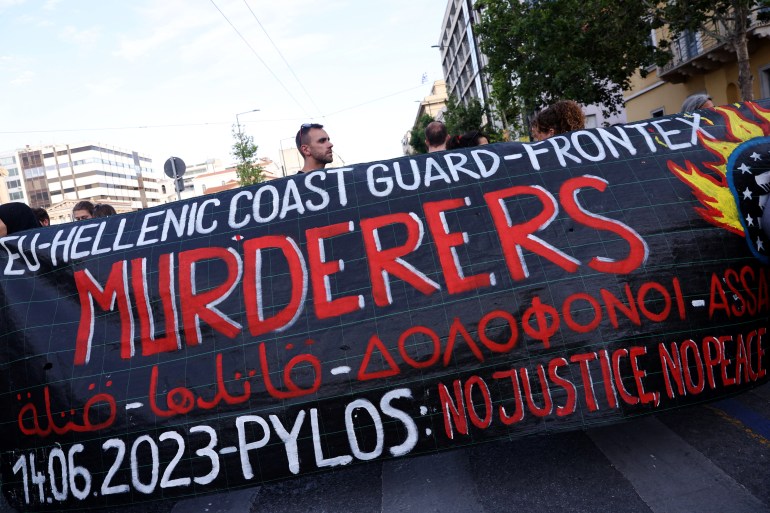

That peril came into sharp relief on June 14, when more than 500 asylum seekers are believed to have drowned following the sinking of their trawler 47 miles (75km) off Greece’s west coast. The vessel had left Libya and was bound for Italy.

A week earlier, EU governments reached an initial agreement on rules for processing asylum applications and for asylum burden-sharing across the bloc.

These are key chapters of a migration pact under discussion for the past eight years, but the agreement involves only how states share responsibility once someone has crossed the external border.

It does not address the issue of how to prevent those crossings from countries like Turkey and Libya bordering the EU.

“There has to be continuous engagement with third countries, and there have to be incentives [for them to take people back],” said an immigration expert with knowledge of the negotiations, who spoke to Al Jazeera on condition of anonymity. “It’s up to us to go out there and talk.”

Signatories to the Geneva Convention on the Status of Refugees of 1951, which include the EU, can either grant refugees asylum or return them to a safe third country.

Sending them to a place where they are at risk is called refoulement.

“Many countries – a large majority of states – want to strengthen this concept … it was agreed that we will return to the discussion in a year,” said a Brussels diplomat involved in the talks.

In theory, a safe third countries policy would be in place by 2026, when the migration pact will enter into force.

Until the EU engages with third countries to negotiate terms of return, say experts, the bloc will have little option but to rescue those who set out across the sea, and those people will have a strong incentive to do so.

“Forty-five percent of asylum applicants [in the EU] receive asylum,” the Brussels diplomat told Al Jazeera on condition of anonymity.

“The rest are supposed to go home, but in practice that doesn’t happen because their country won’t take them, or they refuse to go. Ninety percent of those refused asylum remain, and that is a huge driver for illegal trafficking,” the diplomat added.

The small miracle of solidarity

This month’s initial agreements are still vitally important because they settle a years-long tension between states absorbing migratory flows across the EU’s southern and eastern borders, and those enjoying the relative calm of the hinterland.

Under EU rules, refugees must apply for asylum in the EU state where they first arrived.

Greece and other front-line states in the Mediterranean have long sought a solidarity mechanism that obliges inland states to share the burden of asylum applicants.

Agreement on that mechanism, called the Asylum Migration Management Regulation (AMMR) was a small miracle given that the idea was rejected since it was first presented by the Juncker Commission in February 2015.

The AMMR proposes that a minimum of 30,000 asylum seekers be relocated across the EU.

Countries with higher populations and bigger economies would absorb more applicants than those with lower populations and gross domestic product (GDP).

Member states may refuse (and Poland, Hungary, Czechia, Austria, Denmark and Slovakia did decline to take part in an initial, voluntary scheme in September 2015), but they must now pay 20,000 euros (nearly $22,000) for each applicant they refuse.

The money would pay for refugees’ return and rehabilitation in safe third countries, says the expert.

Allowing countries leeway in what kind of help they offer may have clinched the deal, but rights experts say that flexibility undermines the Geneva Convention.

“A state decides according to its means and ideology, not according to its obligations or responsibilities,” said Nadina Christopoulou, founder of Melissa Network, a migrant women’s organisation in Athens.

Now, she said, “whoever pays decides”.

“We all have the right to ask for asylum – everyone, everywhere … here, we’ve forgotten what a right means,” said Lefteris Papagiannakis, director of the Greek Council for Refugees, a leading legal aid NGO.

But what is a front-line state?

A million asylum seekers entered Europe in 2015, more than 800,000 of them through Greece. The voluntary relocation scheme that year took just under 30,000 asylum-seekers from Greece and Italy.

But recent events have complicated the discussion about what is a front-line state.

“You can’t have a mechanism that is weighted towards the south. The climate is changing very fast,” said the expert.

Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko manufactured a refugee crisis on his country’s borders with Poland and Lithuania in 2021, by flying Iraqi asylum seekers from the Middle East to Minsk and busing them to the border. And the Ukraine war has sent six million Ukrainian refugees into the EU.

“Everyone wants to be a net beneficiary. The Czechs, for example, want to be considered a front-line state,” said the expert.

Secondary migration has also muddied the waters. Irregular migrants who slip into the EU undocumented show up in inland states and apply for asylum.

The solidarity mechanism will work in all directions and could produce surprising results.

“If Greece continues to have reduced flows … and asylum applications continue to flow in Europe from undocumented applicants, Greece could end up being a net recipient,” said the expert.

Greece as ‘test tube’

The pact is codifying rules first designed and applied in Greece by Greek and EU authorities, said the expert.

“Greece had a new [border] procedure that included [the European Border and Coast Guard] Frontex, [the European Asylum Support Office] EASO, police, the [Greek] Asylum Service, the [Greek First] Reception [Service], so a mix of Greek and European bodies,” said the expert.

“There was a security screening, a medical exam, and a vulnerability assessment. The asylum application was then filed and there was a streaming process … some people were judged as ineligible to apply for asylum, others were eligible but had to stay on the island where they arrived, others were classified as vulnerable and could travel freely in Greece – a triage based on the rules we had. That is essentially what the pact is cementing … Greece is a test tube.”

Why, if these rules have effectively been in place for years, did it take so long to standardise them?

Crises may have played a role. The Ukraine and Belarus crises were preceded by a crisis between Greece and Turkey in 2020, after Turkey said it would no longer abide by an agreement with the EU to withhold and readmit undocumented migrants.

Many policymakers believe that the Turkish, Belarusian and Ukrainian refugee crises all aimed to put political pressure on the EU.

“The basic criterion is that migration is constantly on the agenda,” said the diplomat.

“You have crises one after the other, and the recognition that migration is part of the domestic political discussion in each country … everyone knew we had to do something, and if we didn’t reach this imperfect compromise, four years of discussion would have gone out the window.

“And it’s not over,” he said. “We have very difficult discussions ahead of us.”