Costs, COVID, corruption: Anwar’s tasks for Malaysian economy

Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia – In his first address as Malaysia’s 10th prime minister, Anwar Ibrahim pledged to prioritise the welfare of “ordinary Malaysians”.

To make good on his word, Anwar will have to tackle a host of economic challenges, from the lingering scars of the pandemic and rising living costs to a falling currency and one of Asia’s biggest wealth gaps.

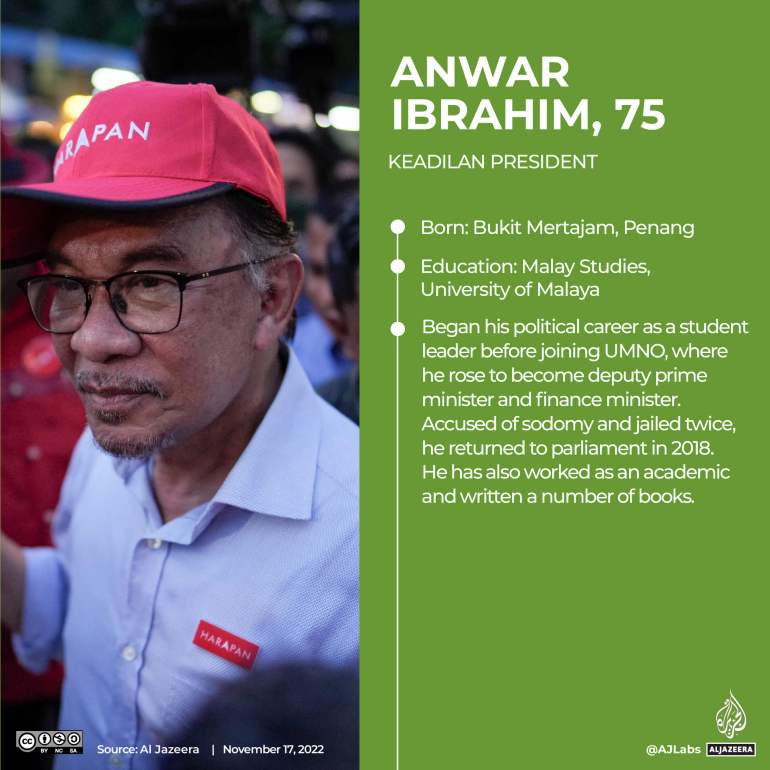

Anwar, whose appointment caps a remarkable three-decade journey from leader-in-waiting to jailed opposition leader and back again, has laid out few specifics of his economic plans apart from promising to tackle the rising cost of living and spearhead development that is racially inclusive and free of corruption.

But Anwar, whose confirmation as prime minister on Thursday after days of political gridlock immediately sent Malaysia’s stock market and ringgit higher, has gained a reputation as a reformist with inclinations towards economic liberalisation throughout his long political career.

“Anwar has a good understanding of the economy and is thoughtful and eclectic in his approach. He is likely to seek a broad range of views and focus on economic reforms,” Geoffrey Williams, an economist and non-resident senior fellow at the Malaysia University of Science and Technology, told Al Jazeera.

“There will be fewer handout-based policies and more structured long-term solutions. I also think he will offer a very attractive prospective for international investors and financial markets.”

On the campaign trail, Anwar, who leads the multiethnic Pakatan Harapan (PH) coalition, highlighted his connections to international business and finance, arguing he could attract investors he counts among his “friends”. He also stressed the need to restore Malaysia’s image overseas, which was battered by the 1MDB corruption scandal involving jailed former Prime Minister Najib Razak.

“Corruption is no doubt Malaysia’s most critical systematic issue that can lead to uneven wealth distribution, compromising the quality of education and healthcare, leading to an overall lower standard of living for Malaysians,” Grace Lee Hooi Yean, head of Monash University Malaysia’s Department of Economics, told Al Jazeera.

“In a corrupt economy, resources are inefficiently allocated and companies that otherwise would not be qualified to win government contracts are often awarded projects as a result of bribery.”

As deputy prime minister and finance minister during the 1990s, Anwar, 75, presided over a boom period that saw Malaysia become one of the fastest-growing economies in the world.

At the onset of the 1997-98 Asian Financial Crisis, Anwar implemented spending cuts and market-oriented reforms recommended by the International Monetary Fund, winning respect in Western financial circles but straining relations with his political mentor and then Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad.

As ties between the two men deteriorated, Mahathir sacked Anwar, who went on to lead the Reformasi movement against the government before his imprisonment on sodomy and corruption charges, which were criticised at home and overseas as politically motivated.

“Given his legacy as the finance minister during the 1990s when the economy enjoyed near double-digit growth aided by manufacturing exports, I expect Anwar to be more market-oriented and favourable to foreign direct investment and infrastructure investment,” Niaz Asadullah, a professor of economics at Monash University Malaysia, told Al Jazeera.

“Compared to past leaders, he’ll seek global integration and strive to repair Malaysia’s tainted international image as an investment destination by aligning domestic policies with global norms and international best practices.”

Asadullah said he expected Anwar’s agenda to be pro-business but also “people-centric”, focusing more on allocating resources on the basis of need rather membership of an ethnic group – a divisive topic in Malaysia, where the majority Malay population receive certain privileges not afforded to the sizeable Chinese and Indian communities.

The last PH government, elected in 2018 in a historic vote that ended six decades of rule by the Malay-majority Barisan Nasional (BN), collapsed in part due to a reform agenda Malay nationalists feared would undermine Malays’ “special position” in the constitution.

“While he’ll remain committed to social protection policies, he’ll seek to minimise fiscal leakages by rationalising subsidies and ensuring smart targeting of resources and services,” Asadullah said.

After suffering the biggest contraction since the 1997-98 Asian Financial Crisis, Malaysia’s economy has rebounded strongly from the pandemic.

Gross domestic product grew by 14.2 percent during the July-September period after an 8.9 percent expansion during the second quarter.

Yet, Southeast Asia’s fourth-largest economy is facing slowing growth amid fears the global economy will tip into recession in the coming months.

Inflation, while modest compared with Europe and North America, and rising interest rates are stretching lower and middle-income households’ budgets thin, while the ringgit hovers near quarter-century lows.

For Malaysia’s longer-term prosperity, structural reforms are needed to ensure its transition to a high-income economy, according to economists.

The OECD and World Bank have highlighted the strengthening of social protections and the introduction of competition in state-dominated sectors such as transport and energy as priorities for reform.

“A prerequisite to achieving a high-income and developed nation is the progression to a ‘high-productivity, high-income’ workforce,” said Lee, the Monash professor. “However, low economic growth has plagued the Malaysian economy after the Asian Financial crisis. One of the main contributing factors to the low growth is the low labour productivity growth.”

As the head of a unity government that includes several rival groupings including the BN, Anwar, whose first tasks will include passing a long-awaited budget for 2023, could find it difficult to implement significant reforms.

“Given the unity government he is heading, it will be tough for him to implement structural reforms quickly without protracted negotiations and consensus among coalition members,” Yeah Kim Leng, director of the Economic Studies Programme at the Jeffrey Cheah Institute on Southeast Asia at Sunway University, told Al Jazeera.

“With the ‘big bang’ likely to be risky and politically destabilising, he will inevitably gravitate towards Deng Xiaoping’s ‘feeling the pebbles while crossing the stream’ that is emblematic of a gradualist approach,” Yeah added, referring to China’s reformist leader who presided over a period of economic liberalisation during the 1980s.

Harris Zainul, a senior analyst at the Institute of Strategic and International Studies (ISIS) Malaysia, said Anwar is unlikely to shake up the status quo due to political uncertainties, including upcoming state elections.

“I don’t expect Anwar to make any big changes in economic policy, especially regarding taxes, in the near term,” Zainul told Al Jazeera.

“Reason being that there is little political appetite to be increasing the tax base right now, with a few key states in Malaysia still needing to have their elections by mid-2023. Until that happens, I don’t think Anwar will be risking anything that may be viewed as politically unpopular.”