Colombia’s historic Truth Commission published its final report. Here are 5 key takeaways

The commission’s final report marks the culmination of hours of interviews with victims, armed actors and public servants involved in the armed struggle between the Colombian state and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC). The commission was established in 2016, as part of a historic peace agreement between the Colombian government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC).

The 800-page report sheds light on human rights abuses and criminal events that occurred in Colombia during the 52-year armed conflict that killed up to 220,000 people and displaced as many as 5 million people.

It also contains recommendations for how the country can move forward, even as fighting continues, despite the 2016 peace deal.

There is an “endless” list of victims

It remains unclear how many people died in the conflict, which touched every aspect of Colombian society, according to the commission. By conservative estimates, according to the National Center for Historical Memory, over 260,000 civilians lost their lives as a result of the violence.

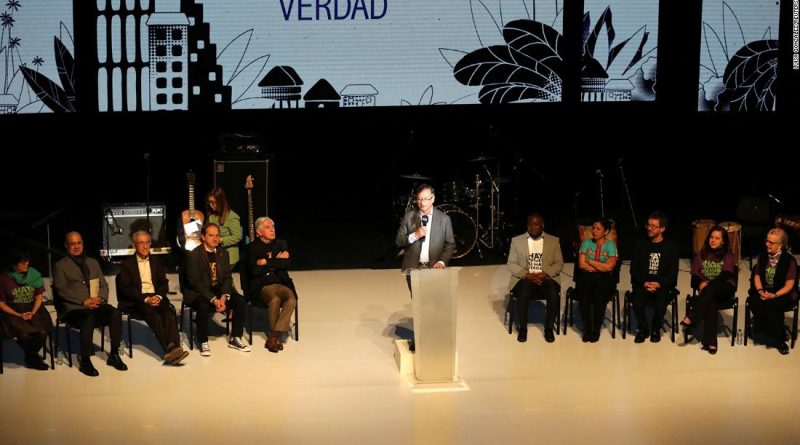

If every named victim of the conflict was to be read aloud it would take over 17 years to go through them all, Father Francisco de Roux, the head of the Truth Commission, said Tuesday.

“The list is endless… the pain is immense,” he said.

The commission also established that the vast majority of the conflict’s victims were civilians, estimating that up to 34,000 children were forcibly recruited by guerrillas in the last 30 years of the conflict alone.

While the focus on Tuesday was devoted to the final, 800-page report on findings and recommendations, the 11-member commission also published nine additional volumes detailing historical events, testimonies and transcripts from over 14,000 interviews from 2016 to 2020.

The military should focus on human rights

The commission said the Colombian armed forces committed human rights abuses and conducted criminal warfare throughout the conflict. They are now calling on the military to undergo widespread reform, saying that “the security approach did not generate security.”

De Roux has urged authorities to refocus the military on human rights and international standards of law, and has also called for the creation of a civil police force. (In Colombia, the police are part of the Ministry of Defense and policemen often train and work with military units.)

Reframe the war on drugs

The commission recommends the government completely change its war on drugs. Drug trafficking is such a pervasive force in Colombian society that it should be considered a political entity and not the target of repressive measures, the report says.

It calls for the end of the practice of aerial fumigations to combat the harvest of coca plants in rural areas, due to the negative impact it has on health, food security and the environment.

And while successive Colombian governments have celebrated the extradition of powerful drug traffickers, the commission advises that it stop approving so many requests to respect the rights of victims. Instead, they advise that drug traffickers face trial in Colombia.

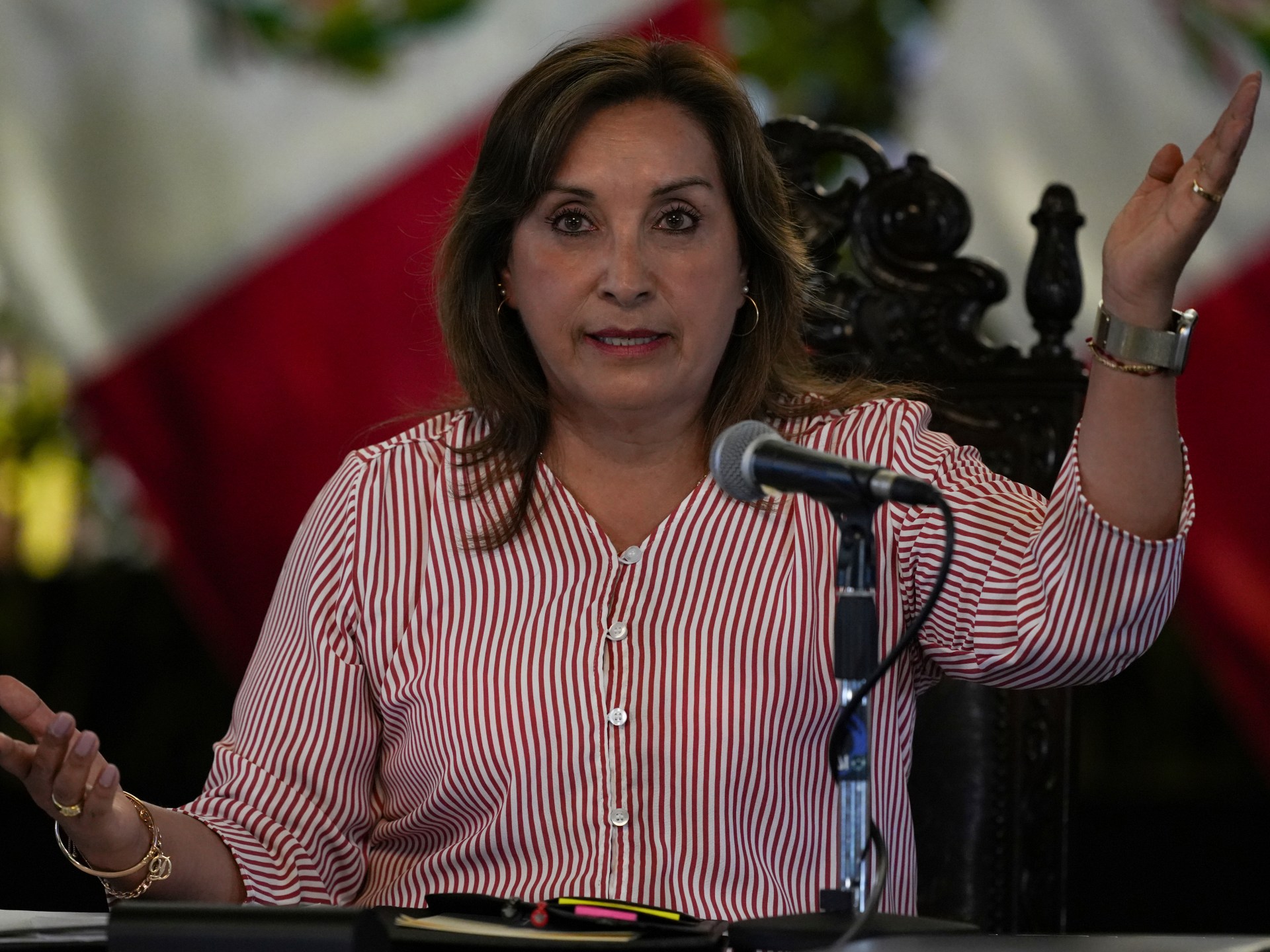

Colombia’s outgoing president was absent

While the commission’s work has been praised at an international level — notably by the US ambassador to Colombia — visibly absent at Tuesday’s event was current President Ivan Duque, who was traveling abroad.

In 2016, Duque campaigned against the peace deal that led to the creation of the Truth Commission and, while he vowed to respect the agreement when he became president, security deteriorated under his watch.

Duque’s party, the Democratic Center, whose leader Alvaro Uribe oversaw one of the bloodiest phases of the armed conflict, released a statement on Tuesday saying: “We don’t think it’s appropriate that anybody established dogmatic or definitive truths in relation to the conflict as there are multiple versions around the events that occurred during the war.”

Meanwhile, President-elect Gustavo Petro, a former guerrilla who was elected as the country’s first left-wing leader in Colombia’s history this month, was present. He received the final report from de Roux’s hands on behalf of the Colombian people. He will be inaugurated in August.

The report isn’t legally binding

Although the commission’s report is the most extensive investigation into human rights abuses and criminal events that took place during the armed conflict, it carries no legal weight.

As part of the 2016 peace agreement, a special Peace Tribunal is tasked with investigating and sentencing armed actors from both the armed forces and the guerrillas.

The Truth Commission’s role was to present recommendations to prevent a similar conflict from happening again.