Can one be African and French?

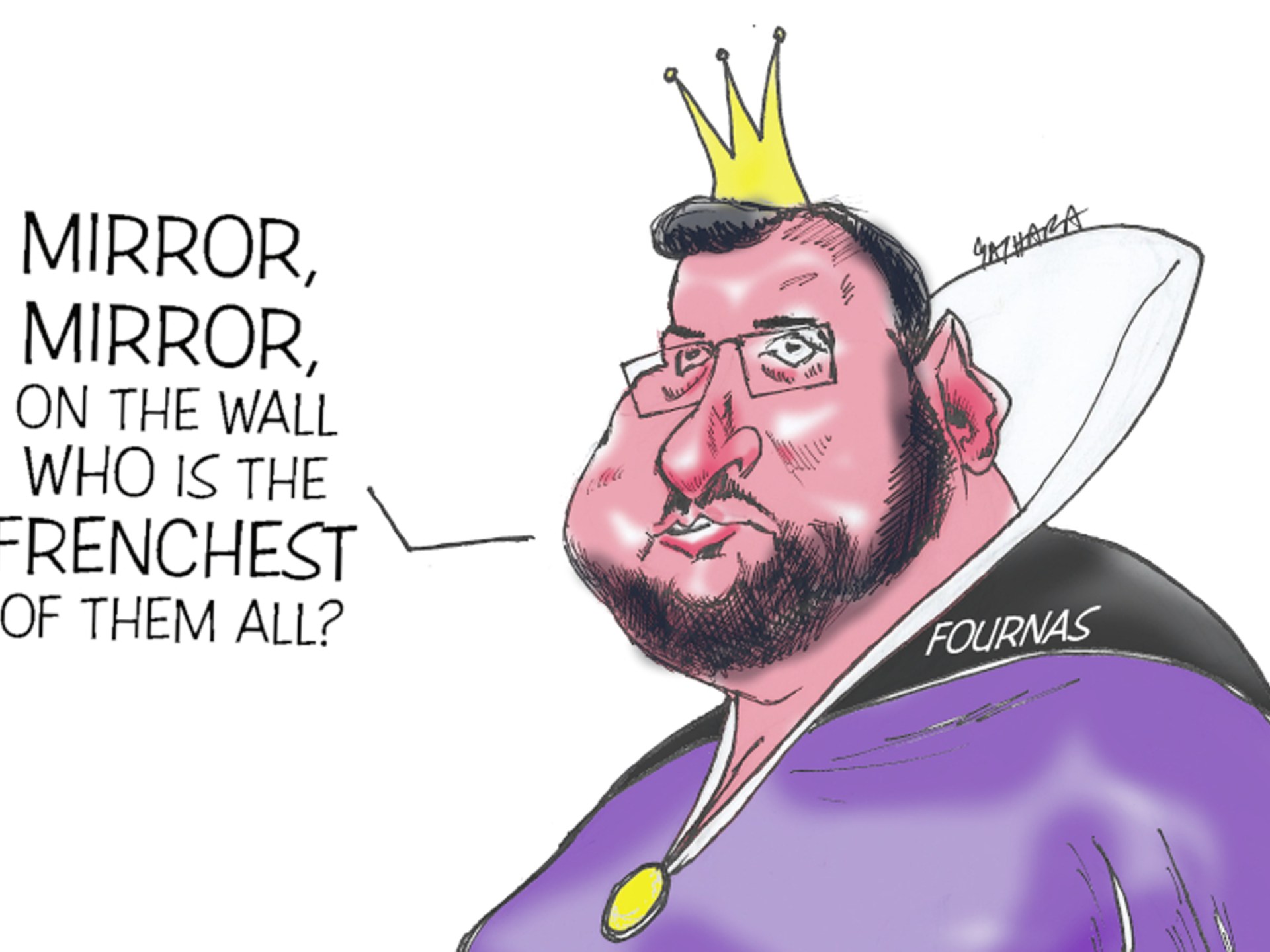

Last week, the French parliament was in an uproar. During a regular session, MP Carlos Martens Bilongo was questioning the government about a ship carrying hundreds of migrants rescued from the Mediterranean still stranded at sea, when he was interrupted by Gregoire de Fournas, a member of the far-right, anti-immigration National Rally. “They should go back to Africa,” de Fournas shouted at Bilongo.

Reactions of outrage followed from across the political spectrum, as many thought the comment was directed at Bilongo himself, who is Black, as the pronouns “he” and “they” are pronounced the same way in French.

De Fournas was handed a 15-day suspension and pay cut despite his protestations that he was referring to the people on the ship and not Bilongo himself.

It is easy to dismiss de Fournas as just another racist ignoramus from the French far right. And he may as well be one. However, he and the liberal politicians defending Bilongo, and even Bilongo himself, may have more in common than they would care to admit. Pronouns were not the only thing that that was in danger of getting mixed up.

“African” and “Black” were seemingly mixed up as well. Clearly, whom de Fournas was referring to would not have been in doubt had Bilongo been anything other than Black. And it did not seem to occur to anyone that the desperate migrants trying to get to Europe could be anything other than African. Yet the tropes of all, and only, Black people being Africans, and Africans making up the majority of people migrating to Europe, are easily debunked.

The episode also brought to mind a clash between South African comedian and US late night TV show host, Trevor Noah, and the French ambassador to the US, Gerard Araud, four years ago.

Commenting on France’s victory in the World Cup in Russia, and the fact that 12 out of 23 French players were Black, Noah quipped, “Africa won the World Cup!” That infuriated Araud, who saw in Noah’s joke an attempt to deny the players’ Frenchness much the same way Bilongo’s colleagues today understand what de Fournas said.

Now, as Noah later explained, context is everything. His use of the word “Africans” to describe French players would not be understood to be a denial of their Frenchness in the same way a racist French politician might use “Africans” to do exactly that. But he went even further to critique the idea that Frenchness and Africanness are mutually exclusive. One might ask, if one can be European and French, why not African and French?

By implicitly accepting de Fournas’s premise of identity as singular and exclusive – that French cannot be African – liberals in and outside the French parliament are unwittingly perpetuating an idea of Frenchness steeped in colonial attitudes of assimilation being an “act of civilising”. They also seem to embrace the imperial perception of people from the African continent as possessing rigid, all-encompassing identities.

The world shaped by colonialism on both sides of the Mediterranean and beyond has come to be defined by the strict European logic of “us vs them”. The French idea of assimilation was meant to turn Africans into one-dimensional Frenchmen, stripped of their alternative histories and the ideas and concepts about identity held by their ancestors.

But other colonial empires were similarly obsessive about regulating and standardising identity. As the late Professor Terence Ranger wrote in a paper marking the 10th anniversary of the his influential book “The Invention of Tradition”: “Before colonialism Africa was characterised by pluralism, flexibility, multiple identity; after it, African identities of ‘tribe’, gender and generation were all bounded by the rigidities of invented tradition” .

The imperial boomerang effect has seen techniques used to control populations in the colonies find their way back home. Identity has become a raging preoccupation of both the Left and Right in Europe, driven by increased immigration. Rigid ideas about what it means to be French or English or American, etc are at the root of the regular complaints across the Western world about the failure of immigrants to integrate, adopt local norms, and learn local languages.

It is ironic that all the furore in the French parliament is much ado about literally nothing. It is well-established in science that every member of the homo sapiens species is of African descent, and rather than being coded into people’s genes, race, nationality, and, as we have seen, tribe, are social and political inventions. Even Africanness, and its association today with Blackness codified in the analytically spurious term “sub-Saharan Africa” or in a less politically-correct “Black Africa”, is a colonial invention.

Rather than accept imperialism’s basis for exclusive identities and the constricted versions of humanity they represent, we need to dismantle them. “Today I was sent back to my skin colour. I was born in France. I am a French deputy,” protested Bilongo.

What he meant was that his skin colour was being used to deny his Frenchness and that it need not be that way. But just as there are many ways to be French, there are many ways to be a human being. And that includes the possibility of being both African and French.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.