As the UK readies its first nationwide Emergency Alerts test this Sunday, here’s everything you need

After officially unveiling its eEmergency Alerts system last month, the U.K. government is preparing to launch the first nationwide test this Sunday (23 April). The system is designed to notify the public of impending danger to life in a specific area.

At 3 pm, all 4G- and 5G-enabled smartphones in the U.K. will receive a message directly to their device, accompanied by a siren-like sound and vibration for up to 10 seconds. The message will say:

This is a test of Emergency Alerts, a new UK government service that will warn you if there’s a life-threatening emergency nearby. In a real emergency, follow the instructions in the alert to keep yourself and others safe. Visit gov.uk/alerts for more information. This is a test. You do not need to take any action.

Similar alerting systems have been used in other countries for some time, including the Netherlands with NL-Alert; the U.S. which has deployed Wireless Emergency Alerts (WEA) for more than a decade; and Canada, which launched its Alert Ready system in 2015. There has been a steady increase in other countries rolling out nationwide alert systems in recent months, including in Germany, Spain, Denmark and Norway.

The need-to-knows

The new alert system is built around so-called cell broadcast technology, meaning it will transmit messages even if a phone is on silent, and also if it’s not connected to mobile data or Wi-Fi. However, it won’t work on devices that are turned off or in airplane mode, devices that are connected to 2G or 3G networks or devices that don’t have any built-in cellular functionality (e.g. devices that are Wi-Fi only). Also, cellular iPad models don’t support Emergency Alerts.

But if you have an Android smartphone or tablet running Android 11 or later that is at least 4G-enabled, or an iPhone running iOS 14.5 or later, you will automatically receive a emergency alert test at 3 pm on Sunday.

Given that this is a test only, recipients don’t actually have to take any action, and the sound and vibration will stop automatically after 10 seconds. To get rid of the message, it’s just a case of swiping it away as you would with any other homescreen notification, or hitting the “OK” button.

U.K. emergency alert in action. Image Credits: U.K. Gov’t.

Only the emergency services or government departments will be able to send these alerts to people’s devices, and in the future users may receive alerts about critical or hazardous events, such as flooding, fires or terrorist attacks.

However, there have been a number of false alarms relating to emergency alerts around the world, including in 2018 when Hawaiian residents were informed of an impending missile attack, which turned out to be a simple case of human error. And just a couple of days ago, Florida residents were awoken at 4:45 am local time by a test alert that was supposed to have been sent out to televisions rather than smartphones.

Red alert

The U.K. launch has been a long time coming. Back in 2010, the former Conservative-Liberal coalition government published The Strategic Defence and Security Review, a paper that addressed many facets of the U.K.’s defence strategy, including its response mechanism to national emergencies. For this, the government said it would “evaluate options for improved national public alert systems for use in major emergencies.”

The focus, ultimately, was to develop a capability to issue alerts to mobile devices in defined areas where an emergency is unfolding. In 2013, the government launched a series of trials in partnership with three of the country’s mobile network operators (MNO) and emergency responders, using different methods to see what was most effective. It initially concluded that location-based SMS was likely the best solution given the existing MNO infrastructure, plus it didn’t require any device-level configuration, with all mobile phone numbers registered to a mobile phone network able to receive alerts.

Not a great deal happened with the U.K.’s emergency alert system in the subsequent years, though the government did use an SMS-based system to send out messages around pandemic-era lockdown rules in 2020, as well as alerts for vaccine accessibility the following year.

But there are downsides to location-based SMS mechanisms. For example, traffic load spikes (e.g. during an emergency) can impact the speed at which messages are delivered, while privacy issues around SMS’s reliance on access to individuals’ mobile phone numbers can be a concern. Cell broadcast technology, on the other hand, allows senders to dispatch messages to all phones in a defined area (i.e. proximity to a cell tower) without requiring access to any mobile phone numbers.

Moreover, cell broadcasts circumvent concerns around traffic load, as cell broadcasts operate on a different channel to voice and SMS.

And that is essentially why the U.K. has elected for a cell broadcast-based system. Some users around the U.K. received cell broadcast-based test alerts in 2021, constituting part of an early pilot in preparation for the broader rollout and nationwide test this weekend.

Opting out

The government reckons that its Emergency Alerts system will cover some 90% of all mobile phones in a given area. And while it goes without saying that it would rather people didn’t opt out to maximize its reach, there may be a multitude of reasons why someone might want to do so. Here’s how you can do so.

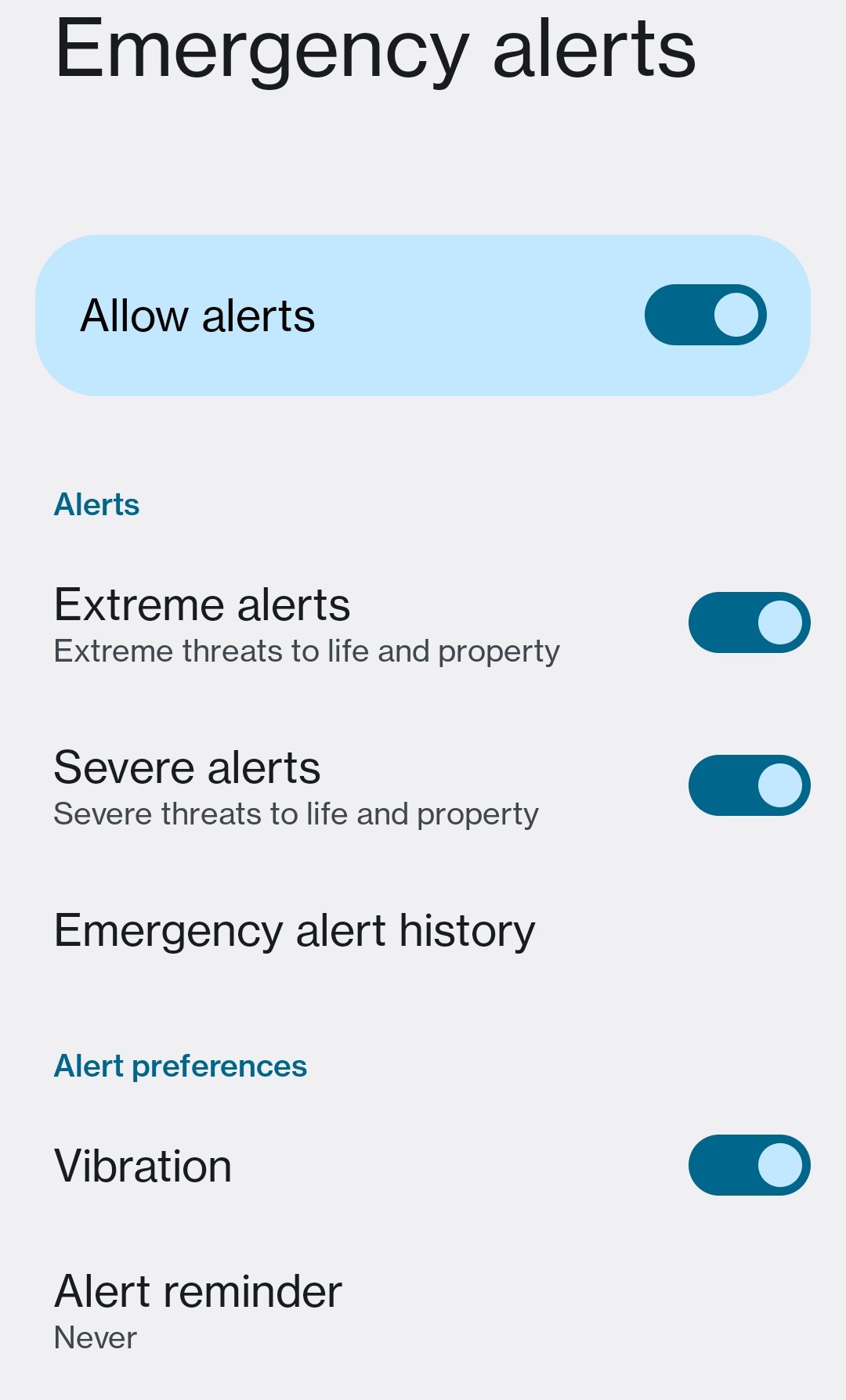

On iPhones, head to Notifications in the Settings menu, and then scroll to the very bottom where you’ll see sliders for Extreme Alerts and Severe Alerts which you can toggle to the Off position. On Android, in settings you can navigate to Safety and Emergency, scroll to Wireless Emergency Alerts and toggle the Allow Alerts slider.

Android emergency alerts. Image Credits: Screenshot/TechCrunch

There have in fact been some concerns from organizations representing vulnerable groups, such as women and children who may be subject to domestic abuse and who may have secondary phones that they conceal from their perpetrators.

“We are concerned about the impact of the Emergency Alerts system on survivors of domestic abuse,” Women’s Aid head of policy Lucy Hadley said in a statement published online. “For many survivors, a second phone which the perpetrator does not know about is an important form of communication with friends or family — as some abusers confiscate or monitor and control their partner’s phone. It may also be their only lifeline in emergencies. The Emergency Alerts pose a risk, not only because an abuser could discover a survivors’ second phone, but also because they could use this as a reason to escalate abuse.”

The government also says it has been working with U.K. transport sector to ensure drivers are aware of the alert and aren’t inadvertently panicked into checking their device when the alarm rings. Needless to say, the normal rules of the road apply with Emergency Alerts — no looking at or interacting with phones while in control of a moving vehicle.