Algeria plays balancing act as Europe tries cut Russian gas

As the Russia-Ukraine war rages on, European Union members are facing a slew of energy security dilemmas.

Dependent on Russia for 40 percent of its gas imports, Italy is looking to reduce this reliance – and quickly – by turning to other countries while accelerating its move towards renewables.

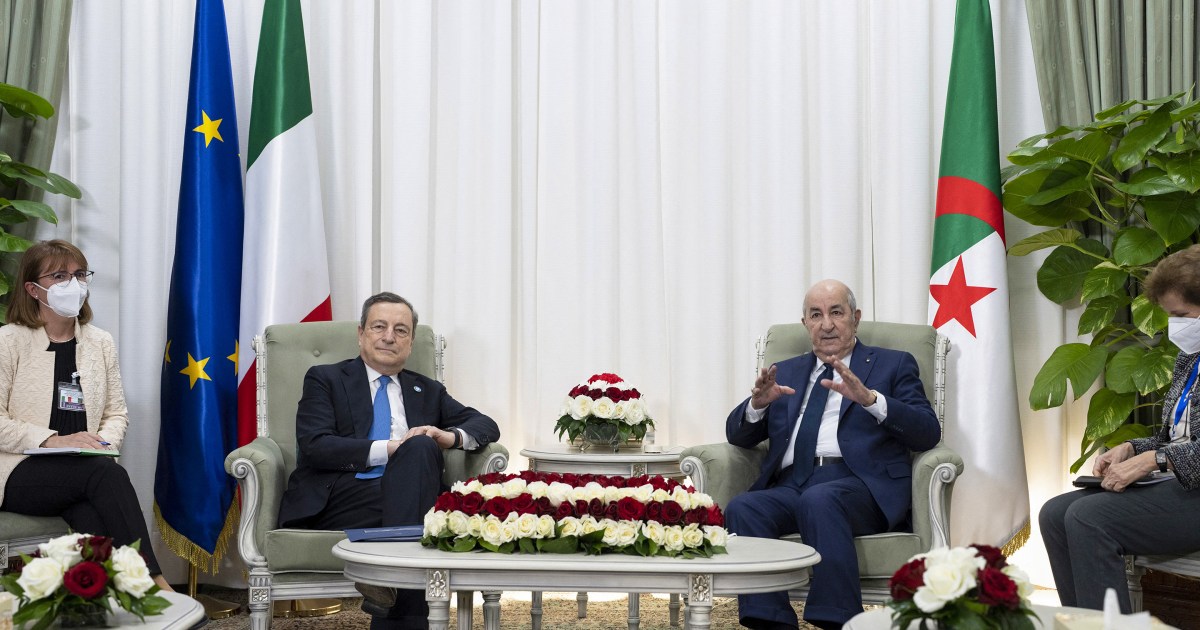

Prime Minister Mario Draghi and the head of the Italian multinational oil and gas company ENI travelled to Algeria in April to sign a preliminary energy deal.

Then, last month, Algerian President Abdelmadjid Tebboune visited Rome to finalise ENI’s agreement with Algeria’s state-owned Sonatrach.

Under the agreement, Algeria is to gradually increase gas flows to Italy via the Transmed pipeline.

While Algeria can ultimately play a useful role in helping Italy reduce its dependence on Russian gas, Italian policymakers have several obstacles to overcome.

In 2010, Algeria was Italy’s top gas supplier but as the North African country had to meet growing domestic demand, exports to Italy have since dropped.

In 2013, Russia became Italy’s number one gas supplier, providing Italy with twice as much gas as Algeria did.

Last year, Russia supplied Italy with 28.988 billion cubic metres (bcm) of gas, compared with Algeria’s 22.584bcm.

Algeria could reroute exports to support Italy and other European countries wishing to wean themselves off Russian gas, a move made simpler given Tunisian imports of Algerian gas have decreased with Algiers making exports to Italy a higher priority.

Yet Riccardo Fabiani, North Africa project director for the International Crisis Group, told Al Jazeera that technical, rather than political, hurdles mean Algeria can probably, at most, reroute only 5-10bcm to Italy and the rest of Europe.

“Domestic demand for gas continues to rise very quickly and there are no significant new projects coming online in the next years that could boost [Algeria’s] production. If anything, total gas production is likely to slightly decrease as pressure at old fields diminishes,” said Fabiani.

The dynamics resulting from increased East-West bifurcation could put more pressure on Algeria to navigate the Ukrainian conflict carefully, against the backdrop of the Algiers-Moscow partnership.

There could be growing concerns in Europe about future gas imports from Algeria benefitting Moscow, considering the North African nation’s significant military purchases from Russia.

Ultimately, Algeria, a country which prioritises foreign policy independence, is attempting to strike a delicate balance in boosting energy exports to EU countries while maintaining its defence relationship and strategic partnership with Moscow.

Since February 24, Algerian officials have sought to keep a degree of equidistance between the West and Russia.

For example, in early May, Russia’s chief diplomat Sergey Lavrov travelled to Algeria just before Lieutenant General Hans Werner Wiermann, head of the NATO International Military Staff, paid a visit.

As a regional heavyweight and former colony, Algeria does not take well to orders from other capitals.

“The roots of this balancing act must be found in the non-alignment movement, where Algeria was at the forefront, which also seems a safe foreign policy choice for many countries in the Maghreb and the developing world – a third way to escape the spiralling and polarisation stemming from the conflict in Ukraine,” Umberto Profazio, an associate fellow at the International Institute for Strategic Studies and Maghreb analyst at the NATO Defence College Foundation, told Al Jazeera.

The fight for Africa’s last colony

A stronger Algerian-Italian energy relationship has ramifications for the Maghreb and Southern Europe.

Last year, President Tebboune halted gas flows from his country to Spain via Morocco amid an intense row.

On June 8, Algeria suspended its 2002 treaty of friendship and cooperation with Spain in response to Madrid endorsing Morocco’s 2007 autonomy plan for Western Sahara in March. That had been a move Spain made to mend fences with Morocco after bilateral relations suffered when the Polisario’s Brahim Ghali received COVID-19 treatment in a Spanish hospital in April 2021, and the subsequent Ceuta crisis.

Will Algeria try to use energy to pressure European governments into adopting increasingly Algeria-aligned positions on Western Sahara?

“Algeria wants to be heard and taken into consideration by its European counterparts, which have been under increasing pressure from Morocco to renegotiate their relations and review their positions on Western Sahara,” said Fabiani.

“Energy is definitely a source of leverage for Algeria and Moroccan diplomats recognise that they cannot expect all Algerian gas-dependent countries in Europe to adopt [Rabat’s] stance on this conflict, which is why there is little pressure on Italy, for example, to change its position on Western Sahara.”

Nonetheless, Algeria’s leverage over European countries vis-à-vis Western Sahara has limits.

If Algiers would attempt to “blackmail” its buyers to change positions on Western Sahara, it would risk jeopardising its role as a reliable energy provider, according to Fabiani.

“European governments need dependable energy exporters and are unlikely to tolerate any blatant exploitation of energy ties for political purposes.”

While turning to Algeria for a strengthened energy relationship, Rome will likely have to pay more attention to Western Sahara, being careful not to upset neither Algiers nor Rabat.

“Italy has not taken a definitive position on the Western Sahara dossier so as to be able to move more freely than Spain in relations with Morocco and Algeria,” said Giuseppe Dentice, the head of the MENA Desk at the Center for International Studies and teaching assistant at the Catholic University of the Sacred Heart in Milan.

Supporting the Polisario is a cornerstone of Algeria’s foreign policy while Morocco views the Western Sahara conflict as its existential issue. But for Italy, this dispute will probably become a diplomatic headache more than anything else.