Abundance on Earth: India’s modern foragers

I run towards the patch of land – recently burned to ashes – while playing hide-and-seek. As a nine-year-old, this is my secret hiding place. It is completely brown, black, and barren. A few days ago, it was a riot of wildflowers dancing in the breeze. But now, nothing. As I hide behind a dry, ash-coloured bush, my eyes catch something. I blink. Wait, is that a leaf? I bend towards it. Yes! A baby leaf happily nodding in the breeze.

I water the plant religiously. One day, I pester my grandmother to come and see my plant. She looks and exclaims: “This is khatti booti [sorrel herb]!” and pats my head. “We make a curry with it.”

“You mean we can eat it?”

“Yes, we can,” she says, and describes how she would accompany her mother to collect edible greens from the grasslands near her village in central India.

The resilience of nature thriving in unexpected places, abandoned plots, concrete crevices, or pavements is amazing. Many of these wild edible plants (WEPs) are neither cultivated nor domesticated but grow on their own and have been foraged for ages. They help the poor make ends meet, alleviate malnutrition, increase food availability, diversify agriculture, and can become a source of income.

Influenced by Grandma’s food wisdom, I explore wild greens wherever I go. I cook ajwain (caraway) leaves, chichardi (solanum anguivi or forest bitterberry), gongura (the south Indian name for sorrel leaves), and kulfa (purslane). I mostly source them from friends who have farmland or the female farmers who sit on the periphery of the local vegetable markets, selling their foraged greens.

Foraging means gathering edible wild plants. Our ancestors foraged as hunter-gatherers and that food knowledge was passed on to generations, surviving largely without documentation.

An exploratory analysis of the number of wild plants eaten in India reveals a huge diversity that includes 1,403 species of plants from 184 families consumed across India.

While foraged plants are a considerable part of the diet of many people around the world, ensuring nutrition and food security, I am most interested in their effect on India and its foodways, and the people who are researching them. How do people forage? And is the food they make with their foraged plants any good?

Nina Sengupta’s black nightshade soup

Ecologist Nina Sengupta, for one, swears by her black nightshade umami soup, made with the leaves of foraged black nightshade, a plant with many nutritional benefits but, she makes sure to stress, it needs to be properly identified and processed.

Cook three cups of washed black nightshade leaves in a litre of salted, boiling water. After about two minutes, drain them and set aside. Soak some shiitake mushrooms in water, cutting them into strips when they soften a bit, then return them to soak. Roughly chop the boiled nightshade leaves.

In a heavy-bottom pot bring a cup of water to the boil, turn the heat down and add shallots, star anise, kefir lime leaves, and coconut milk. Stir for five minutes then add the blanched chopped greens and mushroom strips with their soaking liquid. Stir, cover and cook until the shallots are done. Then add grated ginger, miso, and black pepper. Mix well and cook for two minutes, adjust seasoning and add some sugar if you like.

Let sit, covered, for two minutes and serve hot. Garnish with a pinch of fennel powder and a few cilantro sprigs.

Nina’s foraging journey started when she saw some lal makoi (solanum villosum, or woolly nightshade) growing profusely in Kolkata. Tempted, she collected some ripe fruits to take home for seeds. To her surprise, strangers gathered around and tried to dissuade her from taking them. “Ma’am it will kill you, it’s poisonous,” they fretted.

But Nina knew they were perfectly edible, so she assured her well-wishers that it was safe, but wondered why so many people were detached from nature and what grew in it.

A keen observer of nature, Nina saw that it was unrealistic to expect people to feel anchored in nature and protective of the environment if they only see it on visits to parks. “We need to connect with wilderness in our daily lives,” she said.

Wondering how to encourage more people to do that, she realised: “Tribal people will go foraging for food, medicine, and more. The foodie in me could relate to that,” and could see that was how she could connect others too.

While recovering from an illness shortly after, Nina’s explorations around her home led to the realisation that many of the natural medicines she was prescribed were growing right around her. “It wasn’t that I was going to pluck and make medicines. That wasn’t even important. Just recognising these plants growing near me, as if holding me, gave me a sense of well-being.”

She wanted to keep learning, so she researched online, spoke to people including family, cooks, and market sellers, and read everything she could get her hands on.

What she found made her want to share the knowledge with others in a fun way. So she planned a series of the first-ever adult colouring books in India. The first one – on edible weeds – is now going in for its second edition.

She had first come across the idea of using colouring books to aid learning as a PhD student in the United States when, at the first lecture on genetics, the professor suggested a colouring book of cells.

“This was a ‘Wow!’ moment for me. Doodling and drawing were discouraged from school days. And here is this professor advocating it.” She ran and got herself a colouring book.

The details about the 40 plants – which are found across India – in the book are supported by peer-reviewed journal articles about their edibility, safety, nutrients, and pre-processing.

For readers who want to take it a step further, the book comes with a coloured insert to carry on weed walks to help identify the greens and explain how to use them best.

Permaculturists and forest food growers in India picked up the book. A grower in Auroville, which lies mostly in Tamil Nadu and partly in the union territory of Pondicherry, who runs forest food walks told her walkers about it, leading to more interest and eventually requests for Nina to run weed walks herself. Today, she conducts regular walks, has a podcast called the Heart of Conservation and has a regular social media presence on @edibleweedwalk.

Anandi Zhang Zhang – from China – lives in Auroville and organises Roots, a programme to connect with nature. It included visits to farms, gardens and forests to harvest flowers, vegetables and fruits and cooking sessions to share recipes, laughter, and life experiences. After discovering Nina’s work, Anandi asked her to join them on the nature walks.

For Anandi, this has been a “kind of coming together of science, honouring our deep roots with nature and its abundance”.

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, people worried about food security. “I wasn’t concerned but sure of being sustained by Mother Earth,” Anandi said. “If we know what is available and edible, we will never go hungry.”

Shruti Tharayil’s ‘Ten Leaves’

“Uncultivated greens are often misunderstood and seen as unwanted, invasive, and alien,” says Shruti Tharayil who runs wild food walks and workshops to familiarise people with forgotten greens.

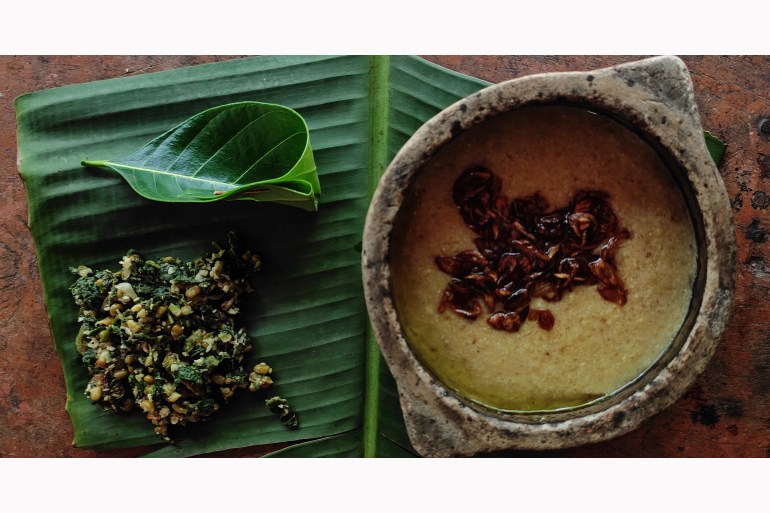

She told me about her recipe for patthila thoran (ten leaves), a delicious dish cooked during Karkidakam (a month of heavy rains in the Malayalam calendar during July-August) in Kerala state. While the recipe varies according to what greens every family has available, at its most basic, patthila thoran combines cooked foraged greens with a generous amount of coconut and the option to add some cooked legumes.

After cooking down shallots in hot oil, Shruti adds chilli flakes and cooks them till their colour darkens, then adds the greens with salt to taste. Once the greens are tender, she adds grated coconut to finish the dish. If she wants to add pigeon peas or split green gram, she adds those and some water with the greens.

Shruti used to think wild plants were inedible until she saw female farmers picking some to eat. “Weeds are considered valueless,” she explains, “but the traditional agriculture accepts and respects the uncultivated plants as a significant part of the ecosystem.”

Intrigued by the nutritional properties of these plants, she started documenting them. She learned about local greens and their recipes from the vegetable vendors and started reaching out to knowledgeable women from rural communities, seeking to work and cook with them. Her beliefs, practices, and ideologies underwent a massive change when she started working with Adivasi (Indigenous) communities.

She was impressed by the efficient, sustainable way of life they had and saw no reason to change it. “Adivasi wisdom and knowledge systems are our keys to reclaim and restore balance on our planet. A large part of my work with forgotten greens is inspired by their way of life.”

She can now be found on social media under @forgottengreens and runs wild food walks in urban spaces to create awareness about wild edible greens growing in concrete jungles.

Using all the means at her disposal, she also offers a weeklong course over WhatsApp about uncultivated greens and does live shows and talks on Instagram.

Priti Vadakkath’s dreamy floral cakes

It is like a dream, one that renders you slightly speechless as you gaze at impossibly fine flowers – red hibiscus, blue pea flowers, variegated leaves of all kinds – lying on a pristine white cake. If you have never had edible flowers before, you may find yourself thinking twice, if only about whether you want to disrupt this tableau.

For Priti Vadakkath, an artist by profession, baking is a hobby while gardening and organic farming are passions.

“Learning happened through experience and inquisitiveness about plants I grow, and research,” she says, adding that, for her, art and design converged with baking as a natural extension of her creative pursuits.

Priti first started using flowers to decorate biscuits she baked, then a friend suggested that she do the same with cakes. Connections with the farming community, a few botanists, and Nina’s colouring book helped Priti tap into their knowledge base about plants and flowers. With some trial, error, and experimentation, she came up with a cake with edible flowers and herbs.

“The technique isn’t new,” she explains. Creative bakers have used edible flowers on cakes for a while now. “The only difference is that by using locally available edible flowers, greens and herbs my cakes and cookies have a unique flavour profile besides the decorative element.”

Among the flowers she uses are roses, morning glories, cosmos, marigolds, hibiscus, amaranthus, tulsi, and moringa. Some come from her own garden and a few are sourced from friends’ gardens.

“I am fascinated by unique cuisines from across the globe that use edible flowers, greens, and weeds and drawn towards the idea and philosophy of growing and foraging for food,” Priti says.

Shweta Mohapatra’s Odia food stories

On Instagram, you will find a serene account, @odiafoodstories filled with beautiful illustrations side by side with photos of greens and the dishes that can be made with them. This is the work of illustrator and graphic designer Shweta Mohapatra, who started this page in 2020 to document Odia (from Odisha state) cuisine.

Using illustrations, recipes, and stories about cooking, Shweta aims to show people that her state’s food is more than just temple food and that its rich and diverse cuisine includes dishes from the Muslim community and various tribes.

While working as an art director for a book project on Odia food, Shweta collected more information than would fit in the book, so she decided to create an Instagram page to share it.

“I decided to illustrate, then cook, write and document,” she explains.

During the COVID lockdowns, Shweta stayed with her parents in Odisha for four months, during which time she encountered many greens from the local tribal markets that she had not seen in other markets.

“You become more sensitive to the weeds and greens. The knowledge is so vast so at times I am happy to discover some familiar greens growing in the parking lot.”

On her Instagram page, Shweta talks about kena saaga (tropical spiderwort) which grows abundantly in fields, sidewalks, back yards, and banana plantations. She recounts how her great-aunt would forage every morning to collect some mixed greens – amaranth, a pumpkin leaf, a small branch of moringa green, and lots of kena saaga – that she would clean, chop, and cook with some vegetables and make a delectable mixed green dish.

Shweta wants to bring wild greens into the mainstream and encourage people to grow, forage or buy them from reliable sources. She reassures people that farmers and foragers will happily share recipes with anyone who asks for them.

Suresh Kumar’s Sarjapura Curries

Artist Suresh Kumar G remembers the wild green curries cooked by his mother as a part of growing up. “I wanted to make videos of my mother’s recipes but sadly, she suddenly passed away.”

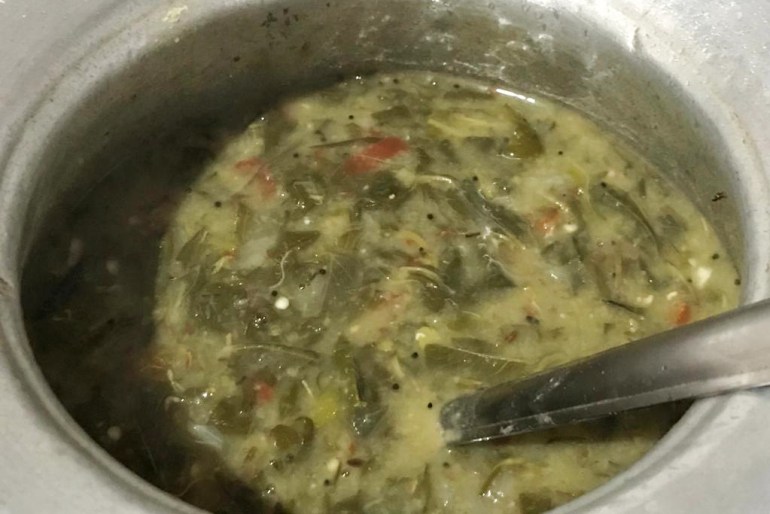

He described his childhood favourite mixed green curry, which is usually prepared with greens foraged by women after the first rains during the evenings before ploughing starts.

A simple hearty dish, it is made by cooking an assortment of tender greens, pigeon peas, onions, tomatoes, green chillies and salt in a pressure cooker. A seasoning of mustard and cumin seeds along with curry leaves is added to the greens and lentil mixture and cooked. It can be served with rice, ragi balls (finger millet) or roti.

Driven by memories, Suresh developed a passion for identifying edible greens with the help of village women, eventually setting up an initiative in his home village of Volagerekallahalli, near Sarjapur, to teach villagers how to grow forgotten seasonal greens.

“I realised that many wild edible plants that were a significant part of our diets were lost and replaced by only a few greens like spinach, fenugreek, and one variety of amaranthus,” he says, adding that the rapid urbanisation that eliminated kitchen gardens and back yards ended the use of edible weeds from cuisines.

He set up Sarjapura Curries in Volagerekallahalli in 2019, helped by a small grant from the Urban Biodiversity Retreat organised by the Bangalore Sustainability Forum.

Before the pandemic hit, he used to share pictures of edible greens on his Instagram account @sarjapura_curries and ran cooking events during the sowing and harvest season, inviting people to enjoy traditionally cooked vegetable dishes.

Suresh was eventually approached by farmers who were interested in planting and marketing these traditional wild herbs, so he set up a WhatsApp group to create a customer base to sell produce sourced from farmers. “We are not foraging in the wild but in the farms by introducing some wild vegetation.”

Among the greens Suresh sells are aggase (mixed amaranthus), rajgira (white amaranthus), peeled and pod sword beans, ivy gourd, turkey berries, pumpkin shoots and flowers, bottle gourd shoots, and nightshade/manthakkali greens.

“What l found interesting about foraging is the experience of walking, discussing and sharing hometown stories and childhood memories and our food culture,” says one of the participants in a weed walk Suresh ran recently.

Srishti Gupta studies at the Kala Bhavana fine arts faculty in Santiniketan, West Bengal, where she is finishing her master’s degree. The opportunity to reach out to others and discuss the similarities in their histories is something she cherishes about the weed walk.

Together the group identified and picked herbs and greens like bhringraj (false daisy) horse purslane, purslane, manathkali (black nightshade) and more. The next day they cooked these greens for a communal meal.

Since then Srishti has been a lot more thoughtful about the food that surrounds her in unexpected places. “The weed walk has made me introspect the choice of the food we eat.”

Oinam Sunanda Devi

Born on the outskirts of Imphal city, Manipur, one of India’s biodiversity hotspots, Oinaam Sunanda Devi was fascinated by the natural beauty of her surroundings. She went on to receive her master’s degree and PhD in ecology, wildlife biology and diversity, travelling to remote parts of Assam and Manipur states for her research papers.

While she was there, she interacted with the locals and began to document the different ethnic cuisines, rituals, and traditions associated with the ingredients, mostly wild edibles, either bought from local markets or collected from the wild.

Her two books, Edible Bioresources and Livelihoods (co-authored with Puspa Komor) and Tradable Bioresources of Assam, offer communities tools and information they need to remain self-sufficient and in touch with their culture in an increasingly industrialised world.

Here, when the pandemic hit, it emphasised “the importance of wild edibles in the life of marginal village communities who can always forage from nearby forests, paddy fields, wetlands, and rivers for personal consumption and for sale in the local markets to earn a livelihood”, Oinam said.

“This region, blessed with several plant and animal species, forms an integral part of everyday life of communities and their culture, traditions and food habits intrinsically linked with changing seasons marked by different festivals calling for specific traditional food preparations,” she explains.

For the Assamese spring festival of Rongali Bihu, for example, 101 elaborate dishes are prepared with leafy vegetables – mostly non-conventional edibles collected from the wild and sold in local haat, village markets.

Leafy edibles, commonly called xak in Assamese, are eaten mostly by simply frying in oil with salt and pepper or as an ingredient in other dishes. Different communities prepare these greens differently, too. While most Assamese people prefer to simply fry these leafy edibles, tribal communities love them boiled with additions like makhana (fox nuts) and bamboo shoots.

The future of foraging

More and more Indians are now foraging in urban spaces as initiatives like nature walks, podcasts, videos and sharing on social media have increased awareness.

Foragers need to keep exploring sustainable ways to replenish resources and keep the habitats healthy to avoid scarcity of these edibles in the future.

“The more the human population, more is our dependency on the natural resources, therefore these non-conventional wild edibles will act as the source of food and livelihood security for many marginalised communities in the coming years,” Oinam explains.

While living in cities has cut us off from nature and natural food, the urge to connect with nature increased during the pandemic.

“If I know a handful of different plants growing around me that are edible at any point then I am climate-resilient and have food security with plants packed with nutrition and micronutrients,” explains Nina.

The more plants you learn to identify, the more fascinating encountering them becomes. “When you encounter beauty there is an opening of the heart,” shares Nina.

Foraging has emerged as a mindful activity that gets people away from screens to where life really thrives.

Latha from Madurai, Tamil Nadu, says: “My foraging walk experience started as a casual fun activity and became a memorable life-enriching experience.”

She found it soothing to walk in bare feet, mindfully observing plants, sharing recipes and memories, remembering playing out in nature and eating all kinds of foraged fruits and berries.

Latha cheerfully walks on the earth, trusting its abundance. To her mind, the only weeds are fear, greed, and a scarcity mindset.

“I walk in nature gently observing all forms of life with awe, admiration, and deep gratitude for keeping me alive.”

Tips for Foragers

If you want to learn more about the plants growing wild around you, getting that information from a knowledgeable source is critical. Not all plants are edible. Not all edible plants are palatable. In fact, one plant might have poisonous, edible, and medicinal parts in it. Remember, do not uproot the plants you pick, as this will kill them.