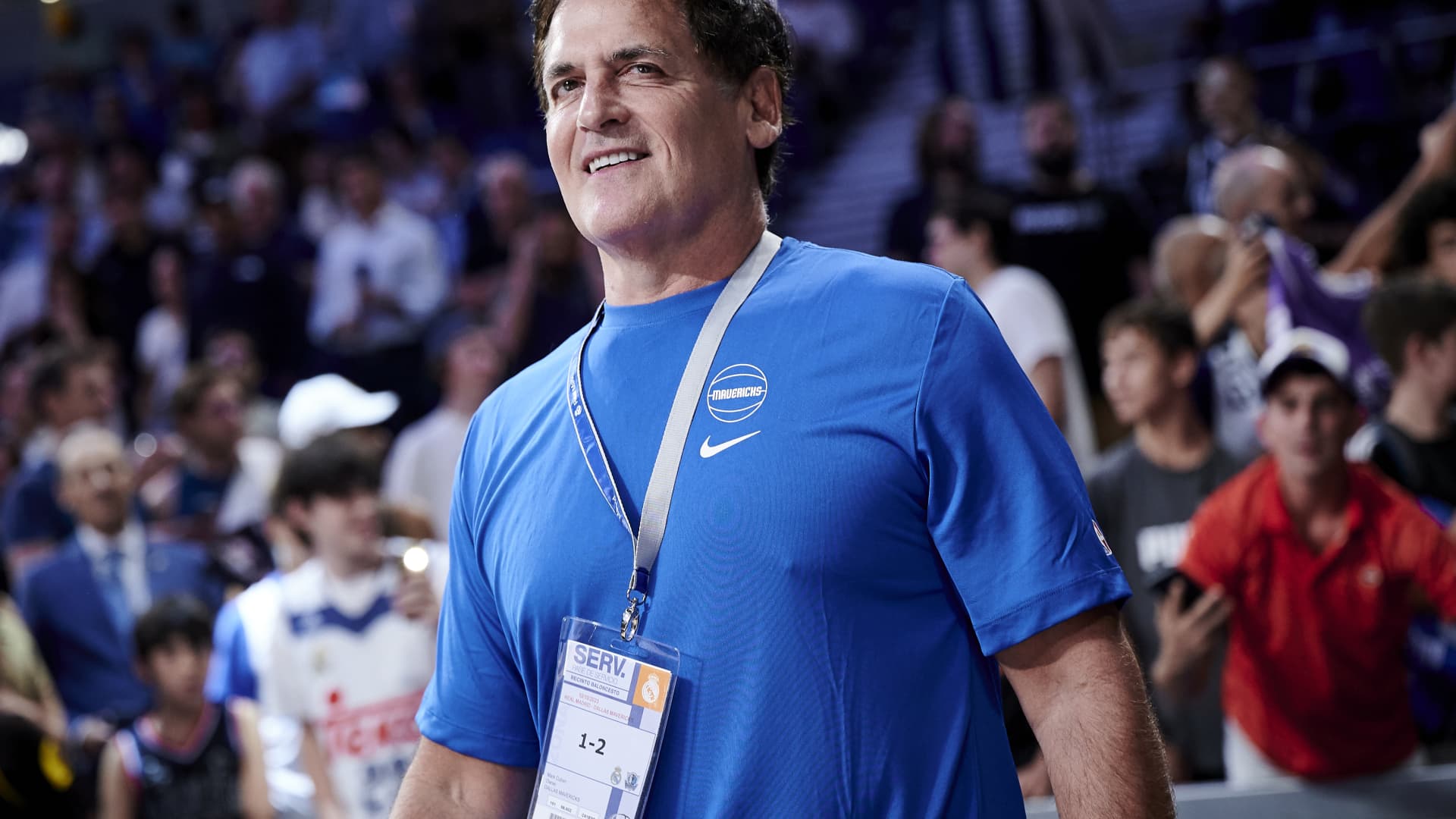

A profile of a negotiator: Gul

What else can we do — this is us. And because we are like this, I tried to find an answer in Brussels. I talked with two types of people.

A proportion of them are people who have worked as EU Commission negotiators. The others are those who negotiated on behalf of member countries. I asked them all the same questions:

Which traits do you think a chief negotiator should have?

Should the individual be multi-lingual?

Should he or she be well versed in European law?

Should the person be a tough negotiator?

Allow me to list the answers I received.

Being multi-lingual is definitely a plus. Knowing a few languages makes the job much easier.

He should either know EU law in detail or his team should be experts on the issue.

The chief negotiator spends most of his time on this matter. If he can pick a good number two, he can delegate some of the burden. However, this job usually requires a timetable that leaves almost no spare time.

If the individual is a internationally known individual and is a capable negotiator, it will be beneficial to the process.

The only precondition is political clout

The most important trait the negotiator should have is political clout. A person who is politically weak cannot force ministries and the bureaucracy to implement necessary reform. One who doesn’t have a very close relationship with the prime minister should not be appointed as the negotiator.

Almost everyone emphasized this matter. One even said: "The matter that results in the biggest waste of time and loss of prestige is the attitude of the negotiator. If this person arrives at a meeting and, for example, says: ‘I am sorry. I couldn’t persuade the farming minister to do what we want. We failed to pass the regulations,’ others will lose trust in that person’s capabilities. Things will drag on; especially if the negotiator and the prime minister are not in complete agreement and the promises made by the negotiator are not kept. That way the process will reach a deadlock."

Who can it be now?

Ever since the Copenhagen summit in 2002, I been thinking about who could be the negotiator.

To tell you the truth, since the beginning, the person I thought would be perfect for the job was Kemal Dervis. I was the first person to suggest his appointment.

Dervis, with his international experience, negotiation skills, knowledge and personality, was perfect for the posting. This decision of ours was taken without consulting Dervis on the matter.

After my visit to Brussels and looking at the profiles of past negotiators, my opinion changed, however.

Eventually, I decided that Foreign Minister Abdullah Gul was the only person who could do the job. The most important reasons behind this change is his political identity, his weight within the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) government, his closeness to Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan and his ability to make the bureaucracy listen to him.

One may know many foreign languages, be an expert in EU law and have great negotiating skills, but political clout is the most important trait.

If Gul forms a team consisting of the most important names from several ministries and select a very good number two and number three, he may be an ideal chief negotiator. His only handicap would be the impossibility of becoming chief negotiator and still being foreign minister. He may be forced to make a choice.

No one should forget that foreign ministers are forgotten after a while, but chief negotiators will always be noted in history.

Chirac is punished over Turkey

Turkey getting a date to start the negotiations on Dec. 17 is not a certainty. The domestic confusion in France is placing great pressure on President Jacques Chirac. All his opponents aim to damage Chirac as much as possible. Some are trying to punish Chirac for saying "yes" to Turkey.

Additionally, the domestic political battles in France are reflected onto Turkey.

You will see that as the pressure on Chirac gets more intense, the number of those countries that are openly against Turkey’s membership will increase. Even now one can see French opposition affecting some other EU countries.

The number of those who are calling for a referendum, or at least a parliamentary vote on giving a date to start the negotiations, are constantly increasing. Their only aim is to create trouble for Chirac. If this proposal is carried out and a vote takes place in the French Parliament before Dec. 17, you will see many others doing the same thing.

Media and public pressure will force governments, even those who support Turkey’s bid, to ask their Parliament for approval.

Everything will become clear within a few weeks. Chirac, as the pressure on him becomes more intense, is trying to deal with the situation with small tactical retreats.

For example, that’s why he accepted a referendum for Turkey’s membership a decade from now. He allowed debates in Parliament to take place, but refrained from calling a vote.

If things continue as they have until Dec 17, Turkey will get a date. If not, the EU may approach Ankara and ask for cooperation in giving a later date.

We can say: "But you said this in Copenhagen in 2002. You cannot take it back. This is unfair and double standards," as much as we want; nothing will change.

Domestic political considerations are always the priority for governments.

What may France want?

There is significant tension in France. They are coming up with many suggestions every day.

One day they ask for the negotiations to start in Dec, 2005, while the next, they suggest 2006 as the appropriate date.

They have yet to agree on the matter. Most probably, they will fail to reach any agreement until the last minute. They may produce a last minute formula based on the latest domestic political considerations.

It appears that Dec. 17 will be a very exciting day.