2022 review: Visualising how the Russia-Ukraine war unfolded

From late February till now, the war in Ukraine has dominated the year’s news agenda like no other story.

Even before Russia’s invasion of its neighbour, months of growing tensions hinted at the risk of a conflict in Europe. But, there was little sense of just how consequential and protracted the fighting would become.

The war has caused tens of thousands of casualties, forced millions from their homes and unleashed a multifaceted global economic crisis.

From battleground gains and losses to mass refugee flows and instrumental weapons supplies, in the maps and charts below Al Jazeera looks at how the war unfolded on the ground, the human costs and global responses.

Taking control on the ground

In late 2021, satellite images emerged showing the buildup of Russian troops on the snowy frontier with Ukraine, raising fears of an invasion. Diplomatic efforts were fruitless and on February 24, Russian President Vladimir Putin in a televised speech announced what he called a “special military operation” to “denazify” and “demilitarise” Ukraine.

People across Europe’s second-largest country woke up to the sound of sirens and explosions as Russian ground forces invaded from four main fronts in the north, northeast, east and south, while artillery and missiles targeted numerous locations.

President Volodymyr Zelenskyy pledged Ukraine will fight back as his government declared martial law and told Ukrainians to take up arms.

In the first month of the war, Russian forces pressed towards Ukraine’s largest cities, including the capital, Kyiv, and the second-largest city of Kharkiv. Moscow’s troops took control of the southern city of Kherson early on, but any Russian aspirations for a swift takeover were stymied by tough Ukrainian resistance.

Bucha, on the outskirts of Kyiv, became a strategic base for Russia’s attempt to advance towards the capital. However, when Russia pulled its troops out of the Kyiv region at the end of March, stating that it would now focus on capturing the eastern Donbas region, evidence of alleged war crimes began to emerge. During a visit to Bucha in April, Karim Khan, the International Criminal Court’s chief prosecutor, described Ukraine as “a crime scene”.

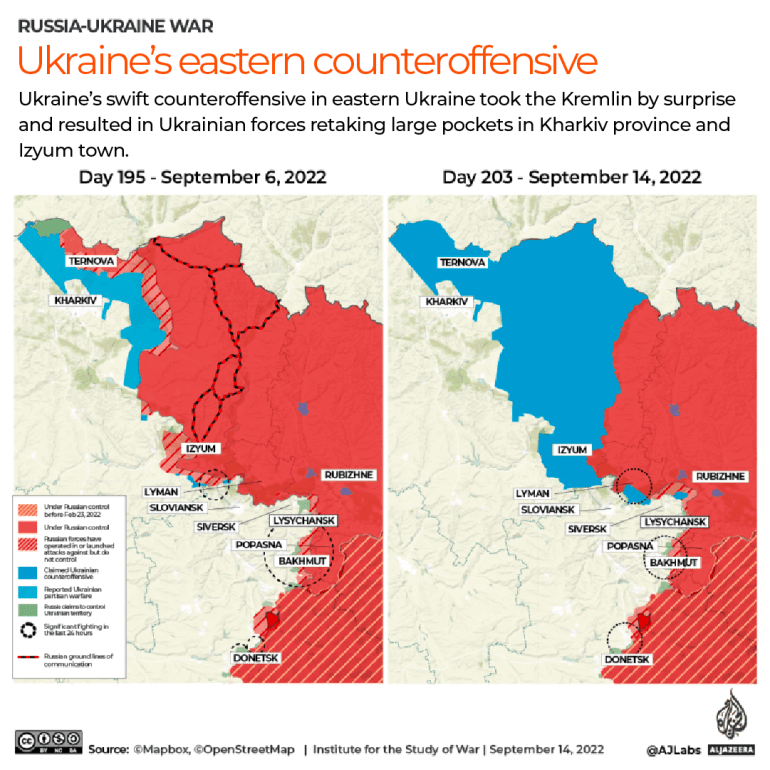

By June, Russia controlled one-fifth of Ukraine, including the southern port city of Mariupol after months of heavy fighting. The front lines largely solidified during mid-year but by early September, Ukrainian forces managed to take advantage of a weaker Russian presence in northeastern Ukraine following the redeployment of Russian fighters to Donetsk and the southern axis, where a Ukrainian offensive in Kherson presented a threat.

The result was a swift counteroffensive that took the Kremlin by surprise and resulted in Ukrainian forces retaking large pockets in Kharkiv province and the town of Izyum – according to the British defence ministry, the retaken territory was at least twice the size of London.

“Within four days, Ukraine nullified four months of success of the Russian army that cost them a huge amount of victims,” Nikolay Mitrokhin, a Russian expert at Germany’s Bremen University, told Al Jazeera.

Putin responded by announcing the annexation of four partially occupied provinces of eastern and southern Ukraine. The move came after voters in Donetsk, Luhansk, Kherson and Zaporizhia backed joining Russia, according to the results of referendums rejected by the government in Kyiv and its Western allies as meaningless and illegal.

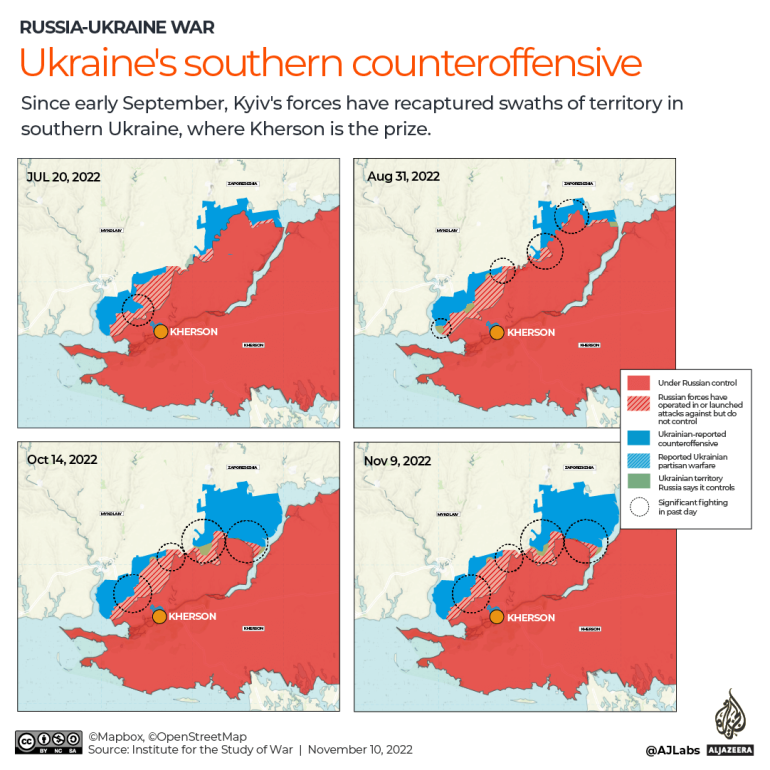

Even though Putin declared that Russia had “four new regions”, calling its residents “our citizens forever”, his troops weeks later retreated from the city of Kherson, the first and only regional capital to be captured by Russian forces since the start of the war.

The decision, Russian officials said, was taken to save the lives of Russian soldiers in the face of a Ukrainian counteroffensive and difficulties to keep supply lines to the strategic city open.

Fighting has since largely focused on Donbas, where Russian forces have for months been battering the city of Bakhmut in Donetsk, at great cost, while Ukrainian troops push towards the key town of Kreminna, in Luhansk.

Human costs

Refugees fleeing

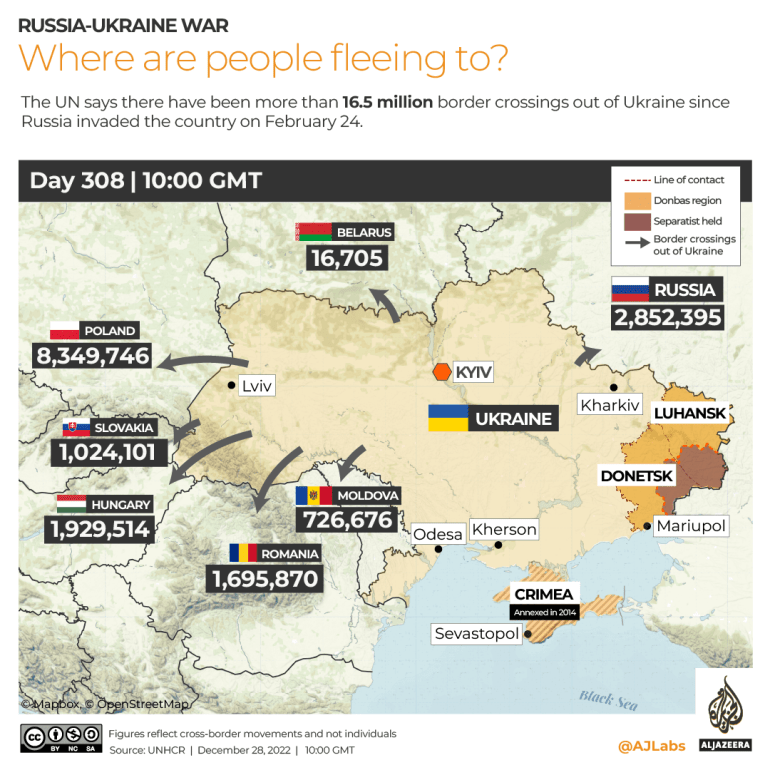

The war has created one of the largest human displacement crises in the world.

About one-third of Ukraine’s more than 40 million population have been forced from their homes at some point since the invasion, with more than 7.8 million refugees heading towards Europe and some six million being internally displaced within the country. The European Union has granted Ukrainians the right to stay and work for up to three years in the 27-member state area.

Since late February, the UN has recorded 16.5 million border crossings leaving Ukraine and 8.7 million entering. Those who have fled Ukraine are mostly women and children, as men aged between 18 and 60 were instructed to remain and fight.

The map below shows where people have been fleeing.

The cost of living

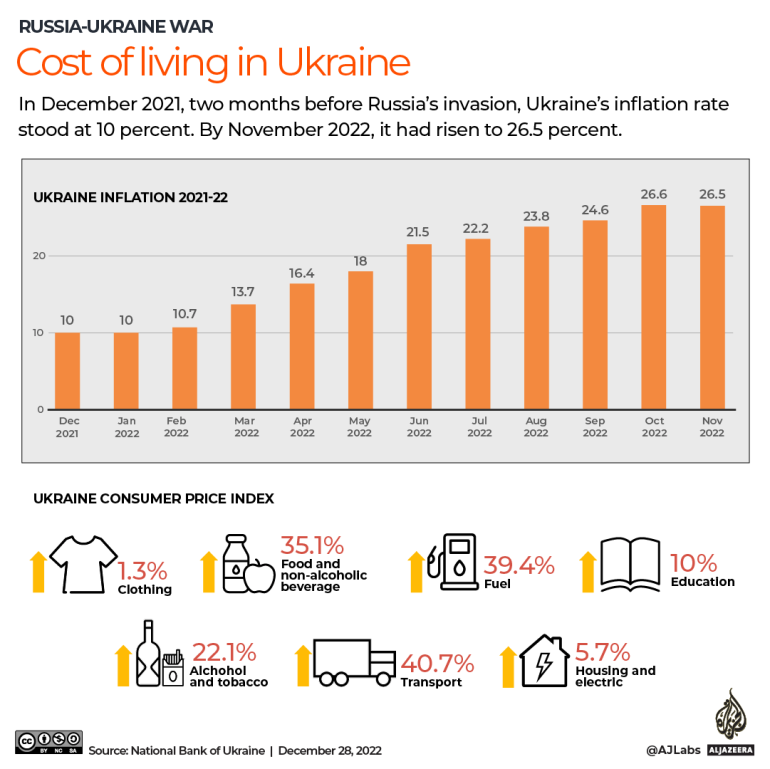

The continuing conflict has led to a global cost of living crisis, with the price of commodities including food items, fertiliser and fuel rising.

In particular, the war exposed Europe’s reliance on Russian energy, while disruptions of grain exports led to rising food prices in countries highly dependent on Ukraine and Russia for such supplies.

The effect has also been felt within Ukraine, which has suffered economic and social losses from damage to infrastructure, labour force dislocation and limited market access.

According to the International Monetary Fund, Ukraine’s gross domestic product (GDP) is expected to drop by one-third in 2022.

In December 2021, two months before Russia’s invasion, Ukraine’s inflation rate stood at 10 percent. By November 2022, it had risen to 26.5 percent. The price of food staples, such as bread, has risen 35 percent, while fuel and transport costs have increased about 40 percent.

Living in the dark

Since October 10, waves of Russian attacks have destroyed or damaged power stations and other infrastructure needed to keep millions of Ukrainians safe from harsh weather conditions.

The attacks have destroyed more than 40 percent of Ukraine’s energy facilities, leaving entire cities without heat and water. Ukraine’s Western allies have said assaults on critical sites are designed to weaponise the winter in Europe.

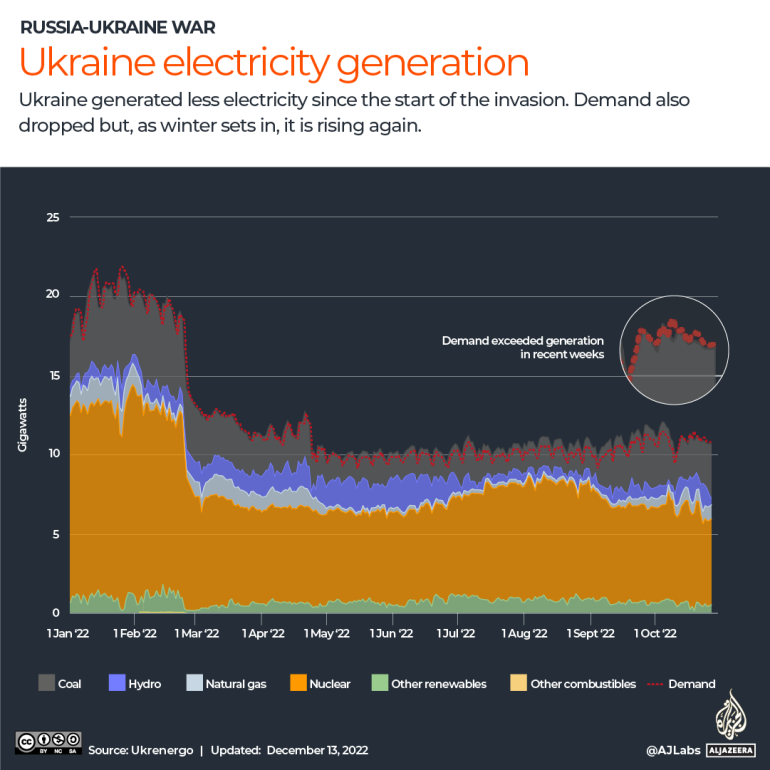

Overall, Ukraine’s energy generation has declined since the invasion, with the sharpest drop in nuclear energy, which powers more than half of the country’s electricity. Demand fell in the first week of the war by about 30 percent, partly because a number of Ukraine’s 15 nuclear reactors were disconnected from the grid when Russia invaded.

With winter conditions setting in, there has been more demand for electricity but rolling blackouts have meant that families used sleeping bags to stay warm, surgeries in hospitals were performed by phone flashlight, and people have tried to find spots in cities where they can charge their phones.

Global response

Sanctions against Russia

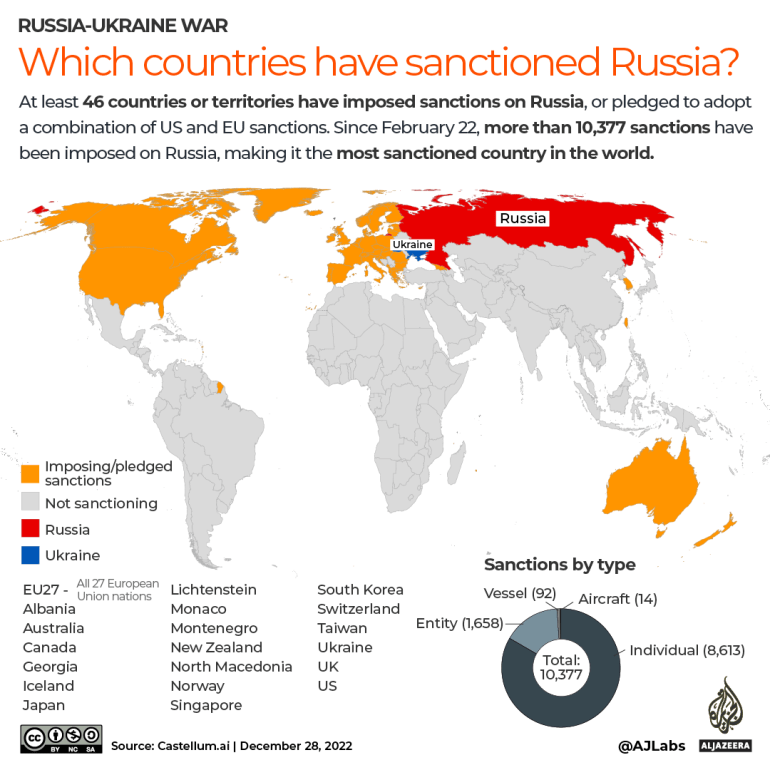

At least 46 countries or territories have imposed a total of more than 10,000 sanctions on Russia over the war, making it the most sanctioned country in the world, ahead of Iran, Syria and North Korea.

Countries and blocs including Australia, Canada, France, Japan, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, the United States and the EU have placed 8,613 sanctions on individuals, 1,658 against entities, 92 against vessels and 14 on aircraft.

By the end of 2022, Russia’s GDP is expected to drop by up to 4.5 percent in the worst-case scenario, according to projections by the World Bank.

Western aid to Ukraine

The US, EU and European states provide most of the military, financial and humanitarian aid to Ukraine, according to data released by the Kiel Institute for the World Economy, a German think-tank.

The figures collected by the Kiel Institute quantify military, financial and humanitarian aid from governments to Ukraine, mainly the EU, and G7 countries. Military assistance includes weapons, equipment and financial aid for the Ukrainian military. Humanitarian relief covers medical, food and other items for civilians, while financial assistance comes in the form of grants, loans and guarantees.

In total, the US has committed about 47.8 billion euros ($50.3bn) of military, financial and humanitarian aid to Kyiv, with almost half coming in the form of military assistance. EU institutions such as the European Investment Bank, the EU Commission and Council, and the European Peace Facility have committed 35 billion euros ($36.8bn) in aid to Ukraine, mostly in the form of financial help. The UK is the third-highest contributor of aid to Ukraine, with 7.1 billion euros ($7.5bn) committed between January 24 and November 20.

Weapons defining the war

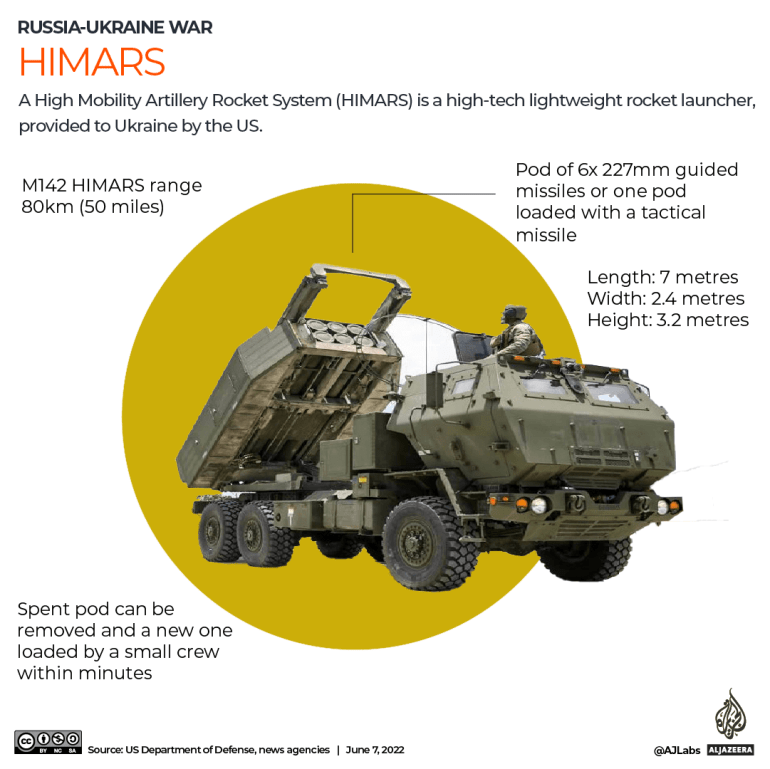

Western military supplies have fuelled Ukraine’s counteroffensives in the northeast and south, helping it regain large swaths of territory. Key among them have been the US-supplied High Mobility Artillery Rocket Systems, or HIMARS.

“HIMARS, along with GMLRs [Guided Multiple Launch Rocket Systems], achieve remarkable strike precision,” said Konstantinos Grivas, who teaches advanced weapons systems at the Hellenic Army Academy, adding that the “Russians have nothing similar”.

In mid-December, the US also agreed to send a Patriot missile battery to Ukraine. The surface-to-air guided missile system is one of the “most widely operated and reliable proven air missile defence systems”, according to Tom Karako, director of the Missile Defense Project at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. The theatre ballistic missile defence capability would be advantageous for Ukraine in its defence against ballistic missiles, which have destroyed critical and energy infrastructure.

Conversely, Russia has lately been taking advantage of so-called “kamikaze” drones to inflict widespread damage, sending volleys of them towards Ukrainian cities and military positions. The Ukrainian government has accused Iran of providing Russia with the low-cost Shahed drones, which carry 40kg warheads and are designed to fly low, thus evading radar. Iran has denied the allegations.