Canada’s restrictive visa policies casting a shadow over IAC 2022

The 24th International AIDS Conference (IAC) is scheduled to take place in Montreal, Canada between July 29 to August 2. Aimed at promoting the latest HIV science and exploring a range of topics from surveillance ethics and health innovation to HIV cure and vaccine research, the conference was expected to bring together tens of thousands of people from diverse backgrounds working to turn the tide on one of the most devastating public health crises of our time.

Regrettably, however, there is now much doubt that this important gathering – the first in-person IAC since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 – will be able to reach its full potential.

Just a week before the beginning of the conference, many delegates from the Global South are still not sure whether they will be able to attend. The host country, Canada, is taking its time in processing the visa applications of prospective attendees from Africa, the Middle East and Latin America. While many delegates are still waiting for their travel plans to be confirmed, more than 100 others have already been forced to accept that they can only attend the conference virtually after their visa applications have been rejected on superfluous grounds.

This is a disgrace. By making it difficult for delegates from the Global South to attend the conference, the government of Canada is not only exposing its discriminatory and harmful immigration policies for the world to see, but also hindering efforts to produce an effective, global response to the threat posed by HIV and AIDS.

Humiliating treatment

The visa hurdles experienced by the prospective attendees of the IAC 2022 were first brought to the global community’s attention in late June, when Keth Monteith, the executive director of the Montreal-based COCQ-SIDA HIV Justice Network, wrote a heavily critical open letter to Canada’s immigration minister Sean Fraser on the issue.

In the letter, co-signed by hundreds of other organisations and individuals, Monteith revealed that he is aware of at least 400 delegates, including some who had already been awarded scholarships to attend the conference, still waiting for a visa response from Canada as well as nearly 100 whose applications had already been rejected.

Since then, countless researchers, advocates and scientists from the Global South talked publicly about the humiliating way Canada’s immigration services treated them as they tried to secure a visa to attend this conference. Some said their applications have been denied because Canadian authorities “did not believe they would leave the country after the end of the conference”. Others revealed that their applications have been rejected after they paid extravagant application fees and spent money to travel to neighbouring countries to give their biometric information to Canadian authorities. Even those who were lucky enough to receive their visas in time complained that Canada needlessly held on to their passports for months, preventing them from travelling elsewhere in the meantime.

In response to the public outcry over its treatment of the Global South delegates, the federal government of Canada finally announced last week that “it is now prioritising temporary travel visas for people seeking to attend the International AIDS Conference in Montreal at the end of July”. The move, however, did little to fix the problem as it will still be impossible for many to receive their visas, book their tickets and arrive in Canada in time for the conference which is due to start next Friday.

Black skin, tough luck

Canada’s discriminatory attitude towards Global South visa applicants is, of course, not exclusive to those attempting to attend the IAC. The country has been making it hard for people from Latin America, the Middle East, parts of Asia and especially Africa to enter the country on short or long-term visas for a very long time. Prejudice against citizens of Global South countries is entrenched in Canada’s immigration architecture.

While activists and applicants themselves have been talking about the issue for years, The House of Commons Standing Committee on Citizenship and Immigration also recently looked into, and confirmed, the prejudice against African nations in the country’s immigration system. After studying the recruitment and acceptance rates of foreign students in Quebec and in the rest of Canada, the Committee found that almost 70 percent of study visa applications from Africa have been rejected in 2021. (The rejection rate is just 41 percent for applications from non-African nations, and goes further down to 17 percent when Indian and Chinese applicants are also excluded.) Refusal rates appear particularly high for students from Ethiopia (88 percent), Ghana (82 percent), and Rwanda (81 percent).

All this demonstrates that Canada is not and has never been the immigrant-friendly “melting pot of cultures” it tries to sell itself as. Sure, its doors are always open to white, rich immigrants from the Global North. But if you are Black, and especially from a middle or low-income country, tough luck – it doesn’t matter whether you are a brilliant scientist, ambitious student or an activist determined to change lives, the Canadian authorities will make it extremely difficult and financially costly for you to enter the country.

Denying visas to IAC delegates is dangerous

For years, Western nations’ discriminatory visa policies have kept people of the Global South off the decision-making tables of countless international conferences and summits. Many valuable scientists, activists and organisers from Africa, the Middle East and the rest of the Global South failed to attend gatherings on climate change, public health and international relations, despite their home countries often being the most impacted by the issues that were to be discussed.

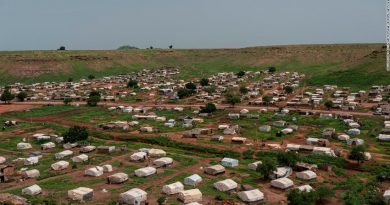

Canada has shown that it has no intention to break this pattern by failing to process the visa applications of IAC delegates from the Global South this year. This failure is especially dangerous, and a threat to the success of the long-awaited conference, because the Global South, especially sub-Saharan Africa, is still the centre of the AIDS crisis, with 60 percent of the 6,000 daily new HIV infections occurring there. What kind of success can this conference have, if the host country excludes sub-Saharan voices from the conversation with bureaucratic hurdles?

Something needs to change, and something needs to change, now. The international community cannot continue to try and address issues that affect us all with conferences only those privileged enough to carry the passport of a rich, Western country can easily attend.

Going forward, visa-restrictive countries, such as Canada, that cannot or will not guarantee access to voices from the Global South should not be allowed to host global conferences on pressing issues like AIDS response or climate change mitigation.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.