Can renewable energy help close power gap in India’s hot summer?

New Delhi, India — As temperatures soar beyond 40 degrees Celsius in Hasanganj village in the northern Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, the nearly 14-hour power cuts in the area mean that the bananas that Ramesh, a fruit vendor who goes by one name, sells are rotting faster than normal with no fans to keep them cool. As sales dip, tempers fray at home, and his children can neither sleep nor study in the searing heat.

The power outages have “aggravated” their problems, Ramesh told Al Jazeera.

As a heatwave rippled through parts of northern India from late March through early May, demand for power shot up, loading power lines and leading to massive outages in several parts of the country as thermal plants ran low on coal.

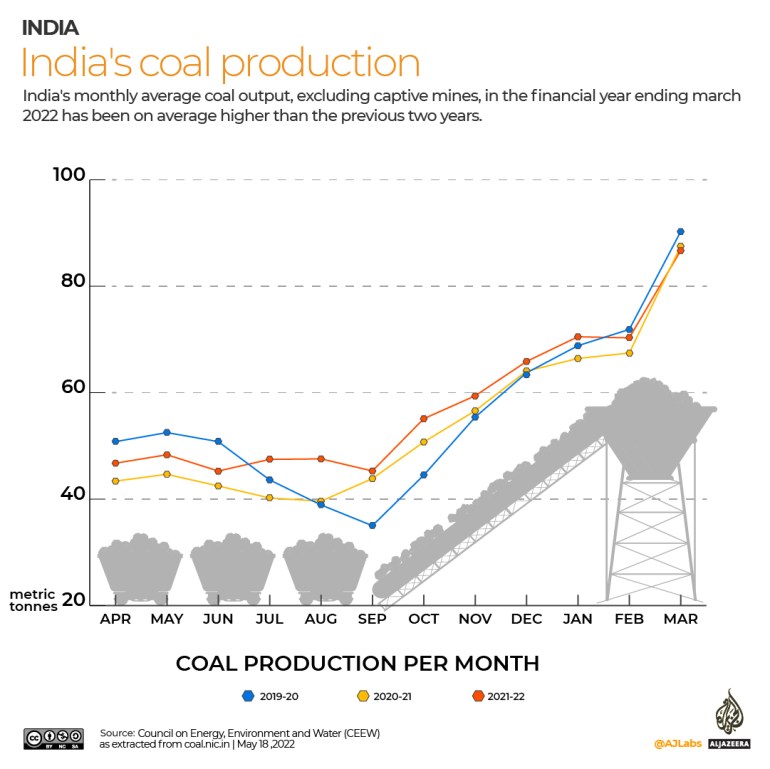

The spate of events, especially as summer has set in sooner and hotter than expected, has renewed a call to dig and import more coal even as India’s coal production has continued to steadily rise. Global coal prices have shot up since the start of the Ukraine war, hiking India’s import costs anywhere from 50 percent to 100 percent, at a time when the rupee has tumbled to record lows, making imports even more expensive.

As a result, on May 7 the environment ministry allowed certain coal mines to expand production up to 50 percent, from the current 40 percent, without seeking the environmental clearances that would normally be mandatory.

#Coal Mines that had received 40% expansion without public hearing (PH) can now expand upto 50% without #EIA/EMP and PH.

Justification: #PowerCrisis #CoalCrisis pic.twitter.com/EPCiANoDmR

— Kanchi Kohli (@kanchikohli) May 10, 2022

A day earlier, the power ministry ordered all power plants that run on imported coal to operate at full capacity and allowed the power producers to pass the hike in tariffs on to consumers.

“The response in the short term is that no matter what, you’ve got to pay the cost to keep the lights on, especially in the middle of a heatwave that will kill people,” said Tim Buckley, the director of Climate Energy Finance, a think-tank in Australia. “But there’s a massive, massive cost to the Indian people.”

One basic cost that Buckley is referring to is the actual price of electricity. While most thermal and renewable electricity in India is sold through long-term contracts, there is still a price difference creeping in for coal power, he says, especially for the 3 to 4 percent that is traded on the exchanges. For instance, of late, while power from domestic coal is being sold at 4-5 rupees/kwh ($0.05-0.06), that goes up to 5-8 rupees/kwh ($0.05-0.10) for power from imported coal (and went up to as high as 12 rupees/kwh or $0.15 on the spot market one day last week). Power from wind and solar, in the meanwhile, is at 3 rupees and 2.5 rupees ($0.03 and $0.04), respectively.

More importantly, adds Buckley, “50-degree heat shows that infrastructure doesn’t work. Coal power plants can’t run above 50 degrees. They break just when you need them.”

Experts say that it’s actually a reminder that India should invest more in its renewable energy to better secure its energy needs.

In fact, late last month as power companies scrambled for coal to burn as demand for fans, coolers and air conditioning rocketed, it was energy from wind plants that came to the rescue as that comes on the grid from late April and runs through August, petering off by mid-September.

“Every unit [of electricity] that wind provides, you generate that much less from coal and that ensures that you’re not in a scarcity mode anymore,” says Karthik Ganesan, a fellow and director in research coordination at the Council on Energy, Environment and Water, a New Delhi think-tank.

‘Fundamental problems’

India gets around 74.4 percent of its electricity from coal-fuelled power plants. Coal shortages are not new to the country – it faced a similar dearth last year – and are more on account of poor planning than any other reason. For instance, last year even though the coal had been dug out of the ground, it lay at the mine mouth and was then flooded under with rains just as demand for it shot up in other parts of the country. Another common problem is the fact that cash-strapped state-run power companies often don’t place coal orders in advance, leading to complaints of shortages when demand soars.

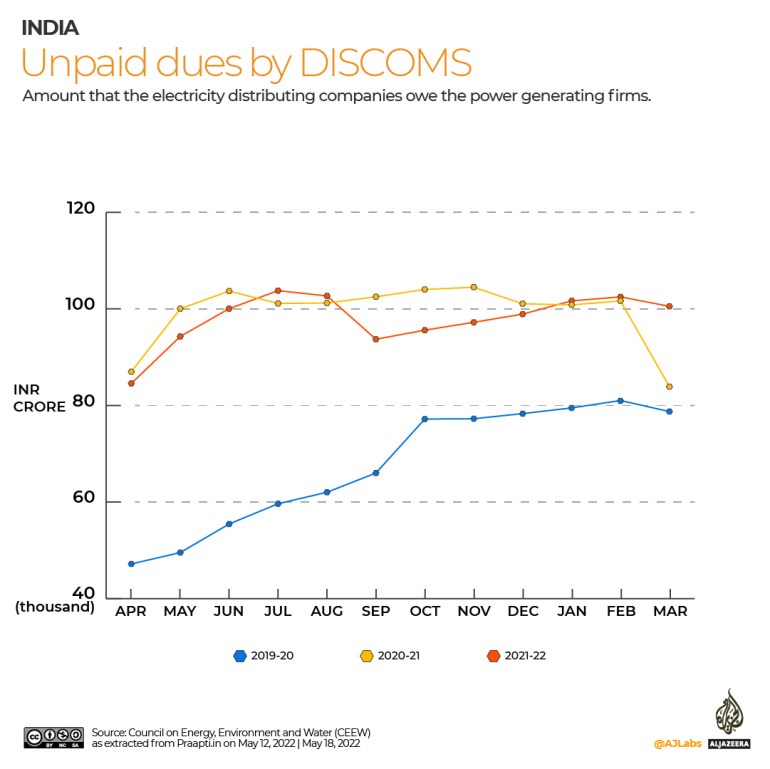

Some of these troubles arise from the fact that in India, electricity is used as political capital – political parties have over the decades offered free, or dirt-cheap, electricity to voters. But ultimately, the cost of that is being borne by the distributing companies as years of unpaid bills mount, leaving them no means to invest to upgrade infrastructure or place coal orders, among other things.

“Sooner or later the government needs to fix the more fundamental problems in the system,” said Ganesan. “Everyone is coughing up dollars [to import coal] because there’s no other option right now and we literally have to throw money at the problem … But instead of fixing the problem, we’re perpetuating it by throwing good money after bad.”

That said, the call to end coal cannot be one to say to stop investing in mining any coal at all. “We don’t want to transition to renewables in a disruptive way that we send people back 30 years…. Climate change is a reality and its impact – high temperatures and a need for air-conditioning – is also a reality,” Ganesan added.

India also needs to step up its renewables game, especially if it truly wants to pare its reliance on coal. As of April, it had 158.12GW of installed renewable energy – which it plans to ratchet up to 500GW by the end of the current decade, a questionable goal as it would need to add around 30GW of renewable power a year, double what it did last year.

For now, it’s the privately run power companies – the ones that have been allowed to pass on the hike in tariffs to consumers – that are smiling their way to the bank, even after accounting for the increase in their costs of importing the coal.

Tata Power, for instance, will run at full capacity its 4,000MW ultra-mega power plant in Mundra in Gujarat – a plant that relies fully on imported coal. Similarly, Adani Power – a part of the diversified Adani Group, which is owned by Asia’s richest man, Gautam Adani – also has a 4,620MW plant in the same region that relies fully on imported coal. (Both companies have investments in renewable power and the latter has announced commitments of $70bn in it.) And even though the state-run distribution companies – the ones that will buy the electricity from these plants – are notorious for not paying on time, or even in full, the companies are still expected to see a boost in profits.

None of that makes any difference to Ishmail Mohammad, who runs a welding business in Hasanganj village. The first couple years of the COVID-19 pandemic devastated his business as many of the local residents – who earned their living by working on construction sites in big cities – had no income to pay him to install metal grills and gates as India implemented multiple lockdowns. Now the nearly 14-hour-long power cuts are just accentuating the pain, especially as prices for the diesel that he runs his generator on, too, have shot up.

“I just can’t work,” he told Al Jazeera. “I can’t even meet my expenses. What is one supposed to do?”