75 years of India partition: How tech is opening window into past

Growing up, Guneeta Singh Bhalla heard her grandmother describe how she crossed into newly-independent India from Pakistan in 1947 with her young children, witnessing horrific scenes of carnage and violence that haunted her for the rest of her life.

Those stories were not in Singh Bhalla’s school textbooks, so she decided to create an online history – The 1947 Partition Archive, which contains about 10,500 oral histories, the biggest collection of partition memories in South Asia.

“I didn’t want my grandmother’s story to be forgotten, nor the stories of others who experienced partition,” said Singh Bhalla, who moved to the United States from India at age 10.

“With all its faults, Facebook is an incredibly powerful tool: the archive was built off of people finding us on Facebook and sharing our posts, which brought much more awareness,” she told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

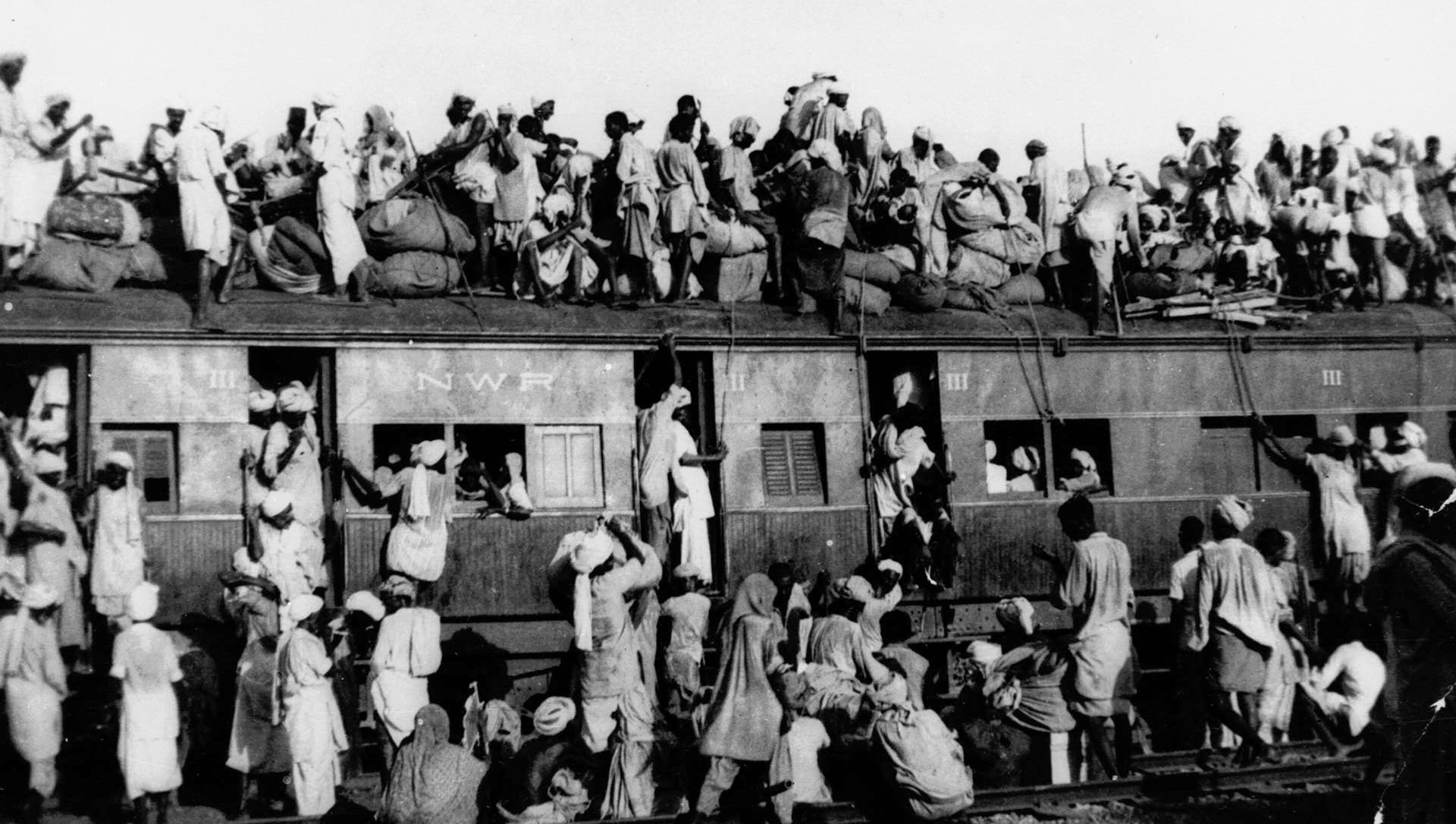

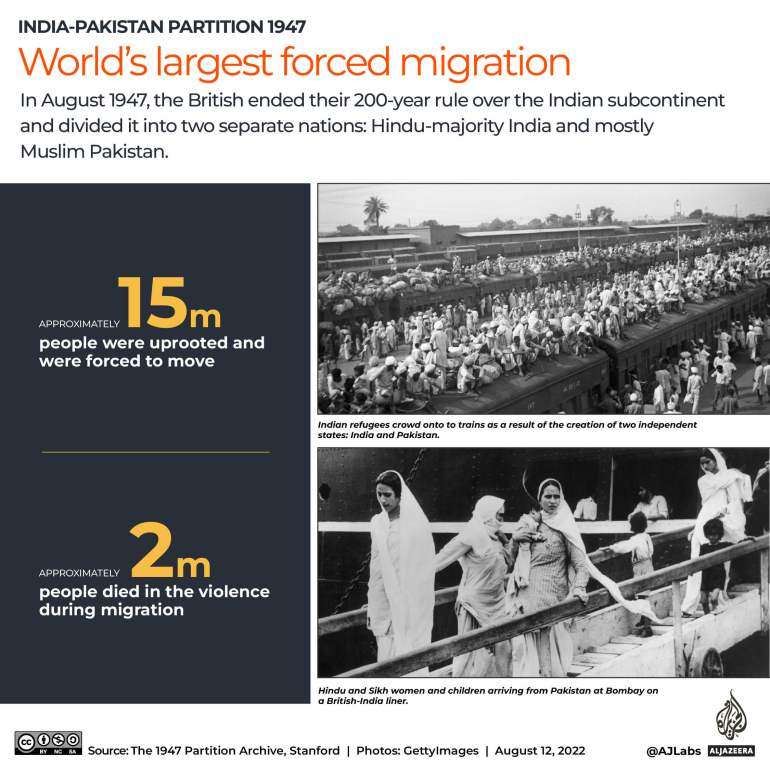

The partition of colonial India into two states, Hindu-majority India and mostly Muslim Pakistan, at the end of British rule triggered one of the biggest mass migrations in history.

About 15 million Muslims, Hindus and Sikhs swapped countries in the political upheaval, marred by violence and bloodshed that cost nearly two million lives.

India and Pakistan have fought three wars since then, and relations remain tense. They rarely grant visas to each other’s citizens, making visits nearly impossible – but social media has helped people on either side of the border connect.

There are dozens of groups on Facebook and Instagram, as well as YouTube channels, that tell the stories of partition survivors and their occasional visits to ancestral homes, that rack up millions of shares and views, and emotional comments.

“Such initiatives that help document the experiences of Partition serve as an antidote to the charged political narratives of the two states,” said Ayesha Jalal, a South Asian history professor at Tufts University in the United States.

“They help to alleviate the tensions between the two sides, and open up channels for a much-needed people-to-people dialogue.”

Virtual reality

As the numbers of those displaced from their homes have swelled worldwide, technology helps monitor abandoned homes from afar and records human rights abuses, while digital archives preserve cultural heritage.

Project Dastaan – meaning story in Urdu – uses virtual reality (VR) to document accounts of partition survivors and enable them to revisit their place of birth.

“VR isn’t like film – there is a level of immersion and engagement that creates empathy and has a powerful impact,” said founder Sparsh Ahuja, whose grandfather migrated to India as a seven-year-old during the partition.

“People really feel like they are transported to the place.”

Using volunteers in India and Pakistan to locate and film places – which have often changed dramatically over the decades – Project Dastaan aimed to connect 75 partition survivors with their ancestral homes by the 75th anniversary this year.

But pandemic restrictions meant that they completed only 30 interviews since they began filming in 2019, said Ahuja.

“When visa policies were more friendly, people could physically go and see places and people,” he said. “Now, these connections wouldn’t happen without technology, and VR has brought a whole new audience to the partition experience.”

Among the most popular YouTube channels on the partition is Punjabi Lehar – or Punjabi wave – with about 600,000 subscribers.

Founder Lovely Singh, 30, part of the minority Sikh community in Pakistan, estimates that the channel has helped 200 to 300 individuals reconnect with family and friends.

Earlier this year, Punjabi Lehar’s video of an emotional reunion between two elderly brothers separated during partition quickly went viral, drawing widespread praise.

“If we can help connect more people, maybe there will be less tension between the two countries,” said Singh.

“This is how my children are learning about the partition.”

Tensions in digital world

India and Pakistan are among the biggest social media markets in the world, with more than 500 million YouTube and nearly 300 million Facebook users, according to research firms Global Media Insight and Statista.

History professor Jalal noted that these online spaces can also host misinformation, and added a note of caution about the limits of social media projects.

“While immensely useful, these initiatives surrounding the partition should not be seen as a replacement to historical understandings of the causes of partition,” she said.

Political tensions between India and Pakistan frequently spill over on to social media.

Last year, one Indian state said people who celebrated Pakistan’s win over India in a cricket match on social media could be charged with sedition, which carries a penalty of up to life in prison.

Indians – particularly Muslims – who criticise the government online are often told to “go to Pakistan”.

But for 90-year-old Reena Varma, social media has done more than make a virtual connection – it has enabled her to visit her old home in Rawalpindi 75 years after she left it.

When her Pakistan visa application was rejected earlier this year, the news went viral on Facebook. Pakistani authorities intervened to give a visa to Varma, who migrated to India as a teenager weeks before the partition.

When Varma visited Pakistan last month, Imran William, founder of the Facebook group the India Pakistan Heritage, was on hand to welcome her.

Residents beat drums and showered her with flowers as she danced on the street, then looked around her old home.

“It was very emotional, but I am so happy I could fulfil my dream of visiting my home,” Varma said.

“People have very painful memories of the partition, but thanks to Facebook and other social media, people are interacting and keen to meet each other. It brings people of both countries together.”