10,000 brains in a basement: The dark and mysterious origins of Denmark’s psychiatric brain collection | CNN

Editor’s Note: Watch the special documentary, “World’s Untold Stories: The Brain Collectors,” November 12-13 on CNN International.

CNN

—

For years, there had been whispers. Rumors swirled; stories exchanged. It wasn’t a secret, but it also wasn’t openly discussed, adding to a legend almost too incredible to believe.

Yet those who knew the truth wanted it out.

Tell everyone our story, they said, about the brains in the basement.

As a child, Lise Søgaard remembers whispers, too, though these were different – the family secret kind, hushed because it was too painful to speak it out loud.

Søgaard knew little about it, except that these whispers centered on a family member who seemed to exist solely in one photograph on the wall of her grandparent’s house in Denmark.

The little girl in the picture was named Kirsten. She was the younger sister of Søgaard’s grandmother, Inger – that much she knew.

“I remember looking at this girl and thinking, ‘Who is she?’ ‘What happened?’” Søgaard said. “But also this feeling of a little bit of a horror story there.”

As she grew into adulthood, Søgaard continued to wonder. One day in 2020, she went to visit her grandmother, now in her mid-90s and living at a care home in Haderslev, Denmark. After all that time, she finally asked about Kirsten. Almost as if Inger had been waiting for that very question, the floodgates opened, and out poured a story Søgaard never expected.

Kirsten Abildtrup was born on May 24, 1927, the youngest of five brothers and her sister, Inger. As a child, Inger remembers Kirsten as quiet and smart, the two sisters sharing a close bond. Then, when Kirsten was around 14 years old, something began to change.

Kirsten experienced outbursts and prolonged bouts of crying. Inger asked her mother if it was her fault, often feeling that way because the two girls were so close.

“At Christmas, they were supposed to go on a visit to some family members,” Søgaard said, “but my great-grandmother and father, they stayed home and sent all of their children away except for Kirsten.”

When they got back from that family visit, Søgaard said, Kirsten was gone.

It was the first of many hospitalizations, and the start of a long and painful journey that would ultimately end in Kirsten’s death.

The diagnosis: schizophrenia.

Kirsten was first hospitalized towards the end of World War II, when Denmark and the rest of Europe were at last on the verge of peace.

Like so many places, Denmark was also grappling with mental illness. Psychiatric institutions had been built across the country to provide care for patients.

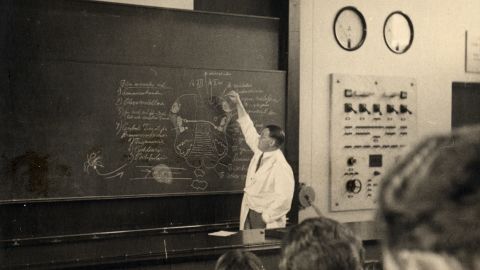

But there was limited understanding of what was happening in the brain. The same year peace came to Denmark’s doorstep, two doctors working in the country had an idea.

When these patients died in psychiatric hospitals, autopsies were routinely performed. What if, these doctors thought, the brains were removed – and kept?

Thomas Erslev, historian of medical science and research consultant at Aarhus University, estimates that half of all psychiatric patients in Denmark who died between 1945 and 1982 contributed – unknowingly and without consent – their brains. They went to what became known as the Institute of Brain Pathology, connected to the Risskov Psychiatric Hospital in Aarhus, Denmark.

Doctors Erik Stromgren and Larus Einarson were the architects. After roughly five years, said Erslev, pathologist Knud Aage Lorentzen took over the institute, and spent the next three decades building the collection.

The final tally would amount to 9,479 human brains – believed to be the largest collection of its kind anywhere in the world.

In 2018, pathologist Dr. Martin Wirenfeldt Nielsen got a call. The brain collection, as it would come to be known, was on the move.

A lack of funding meant it could no longer stay in Aarhus, but the University of Southern Denmark in the city of Odense had offered to pick up the mantle. Would Wirenfeldt Nielsen be interested in overseeing it?

“I’d sort of heard of it in the periphery,” Wirenfeldt Nielsen recalled. “But my first real knowledge about the vast extent of it was when they decided to move it down here … (because) how do you actually move almost 10,000 brains?”

The yellowish-green plastic buckets housing each brain, preserved in formaldehyde, were placed into new white buckets that were sturdier for the transport, and hand-labeled in black marker with a number. And then the brains, give or take a few (no one knows where bucket #1 is, for example) made their way to their new home in a large basement room on the university’s campus.

“The room wasn’t actually ready when they moved it down here,” Wirenfeldt Nielsen said. “The whole collection was just standing there, buckets on top of each other, in the middle of the floor. And that’s when I saw it for the first time … That was like, okay, this is something I’ve never seen before.”

Eventually, the nearly 10,000 buckets were placed on rolling shelves, where they remain today – waiting – representing lives, and a range of psychiatric disorders.

There are roughly 5,500 brains with dementia; 1,400 with schizophrenia; 400 with bi-polar disorder; 300 with depression, and more.

What separates this collection from any other in the world is that the brains collected during the first decade are untouched by modern medicines – a time capsule of sorts, for mental illness in the brain.

“Whereas other brain collections … (are) maybe specified for neurodegenerative diseases, dementia, tumors, or other things like that – we really have the whole thing here,” Wirenfeldt Nielsen said.

But it has not been without controversy. In the 1990s, the Danish public got wind of the collection, which had been sitting idle since former director Lorentzen’s retirement in 1982.

It would kick off one of the first major ethical science debates in Denmark.

“There was a discussion back and forth, and one position was that we should destroy the collection – either bury the brains or get rid of them in any other ethical way,” said Knud Kristensen, the director of SIND, the Danish national association for mental health, from 2009 to 2021, and current member of Denmark’s Ethical Council. “The other position said, okay, we already did harm once. Then the least we can do to those patients and their relatives is to make sure that the brains are used in research.”

After years of intense debate, SIND changed its position. “All of a sudden, they were very strong proponents for keeping the brains,” Erslev said, “actually saying this might be a very valuable resource, not only for the scientists, but for the sufferers of psychiatric illness because it might prove to benefit therapeutics down the line.”

“For (SIND),” Kristensen said, “It was important where it was placed and to make sure that there would be some sort of control of the future use of the collection.”

By the time it moved to Odense in 2018, the ethical debate was largely settled, and Wirenfeldt Nielsen became caretaker of the collection.

A few years later, he would get a message from Søgaard. Was it possible, she asked, that he had a brain there belonging to a woman named Kirsten?

In the search for what happened to her great aunt Kirsten, Søgaard realized there were clues all around her. But piecing together what exactly had happened to her grandmother’s sister was slow, filled with dead ends and false starts.

Yet she was enthralled, and began officially reporting her journey for Kristeligt Dagblad, the Copenhagen-based newspaper where she worked – eventually bringing it to light in a series of articles.

At one point, Søgaard decided to focus on a single word her grandmother had told her, the name of a psychiatric hospital: Oringe.

“I opened my computer and I searched for ‘Oringe patient journals,’” she said. After putting in a request through the national archives, “I got an email that said, ‘Okay, we found something for you, come have a look if you want.’ … I felt this excitement … like, she’s out there.”

That excitement was short-lived. At the national archives, they placed a mostly empty file in front of her. It wasn’t much to go on, but it confirmed Kirsten’s diagnosis of schizophrenia.

Without another solid lead, Søgaard wondered where to go next. Then, almost in passing, as they looked through old family photos together, her mother said something that she’d never heard before.

“She said, ‘You know, they might have kept her brain,’ and I said, ‘What?!’” Søgaard told CNN’s Dr. Sanjay Gupta at her house outside of Copenhagen. “And she told me what she knew about the brain collection.”

At age 95, Søgaard’s grandmother, Inger, could still clearly picture visiting her little sister Kirsten in the hospital, after the symptoms she first started experiencing at age 14 continued to progress.

Upon one visit, Inger remembered, “(Kirsten) was lying there, completely apathetic. She was not able to speak to us. … Another day we went to visit her, and she was gone from her room. They told us she had thrown a glass at a nurse, and they had sent her to the basement, to a room where they (restrained) her with belts. And we were not allowed to go in, but I saw her through a hole in the door; she was lying there, strapped up.”

Inger felt confused and scared, she said, because it could have been anyone, including her, that might get “sick.”

At Sankt Hans, one of the largest and oldest psychiatric hospitals in Denmark, Dr. Thomas Werge walks the same grounds he did as a child, when his own grandmother was hospitalized there. Now, he runs the Institute for Biological Psychiatry there, where he and his team study the biological causes that contribute to psychiatric disorders.

A 2012 study found that roughly 40% of Danish women and 30% of Danish men had received treatment for a mental health disorder in their lifetimes – though Werge estimated that number would “almost certainly” be higher if the same study was done today. (By comparison, that same year, less than 15% of US adults received mental health services.) Among the other Nordic countries, including Sweden and Norway, Werge said the numbers would be comparable to Denmark’s, as there are “similar [universal] health care systems and standards for admission.”

“Mental (health) disorders are all over,” he added. “We just do not recognize this when we walk around among people. Not everybody carries their pain on the outside.”

For schizophrenia, there are no blood tests or biomarkers to signify its presence; instead, doctors must rely only on a clinical exam.

Schizophrenia presents itself in what the World Health Organization (WHO) calls “significant impairments in the way reality is perceived,” causing psychosis that can include delusions, hallucinations, disorganized behavior or thoughts, and extreme agitation.

Roughly one in 300 people are affected by schizophrenia worldwide, according to the WHO, but less than one-third of those will ever receive specialist mental health care.

Visiting a ‘cemetery of the brainless’ in Denmark

02:10

– Source:

CNN

The standard treatment since the mid-1950s has been anti-psychotic drugs, which typically work by manipulating dopamine levels: the brain’s reward system. But, Werge said, it can come with a cost.

“Schizophrenia and psychosis are linked to creativity,” he said. “So, when you try to inhibit the psychosis, you also inhibit the creativity. So, there’s a price for being medicated … Whatever causes all these problems for humans is also what makes us humans in the good sense.”

Though there haven’t been many significant scientific breakthroughs regarding an understanding of the disease, researchers have confirmed that genetics and heritability play a significant role.

According to Werge, the heritability estimate is as high as 80% – the same as height. “It’s not a surprise to people that if you have very tall parents … there’s a lot of genetics in that,” he said. “The genetic component is equally large in most of the mental disorders actually.”

Those inherited genetic factors either come from the parents, he added, or can arise in a child even if the parents don’t carry the gene.

Søgaard, who has two young children, said the genetic connection was not a driving motivator in her mission to find out what happened to Kirsten, but she has thought about what it means for herself and her family.

When families reach out about possible relatives in the brain collection, “that’s an ethical dilemma that we need to take into consideration,” Wirenfeldt Nielsen said. In Søgaard’s case, she received approval for the Danish National Archives to check the set of black books that contain the names of every person whose brain is in the collection.

There on the list was Kirsten’s name.

“I got an email back [from the National Archives], and they scanned the page where Kirsten’s name was, and her birthday, and the day they received the brain. And in the column out to the left, there was a number,” Søgaard remembered. “Number 738.” She immediately wrote an email to Wirenfeldt Nielsen, asking if that number corresponded to the bucket with Kirsten’s brain.

“I said, ‘Yes, that’s it,’” Wirenfeldt Nielsen recalled. But he also said he couldn’t be sure the bucket was there because a few are missing for unknown reasons. He ventured down to the basement storage room to verify it was there.

On one of the rolling shelves sat bucket #738.

Kirsten’s brain.

When Søgaard first saw it, she felt compelled to hug the bucket.

“I had learned a lot about Kirsten,” she said. “I feel some kind of connection … (and) I know the pain that she felt, and I know what she went through.”

What Kirsten went through was another extraordinary beat in this incredible story, and the long history of psychiatric care in Denmark.

As part of her treatment, Kirsten received what’s known commonly in Denmark as “the white cut.”

In medical terms: a lobotomy.

The procedure was an integral part of the country’s psychiatric history. During the time the brain collection was running from the 1940s until the early 1980s, Denmark reportedly did more lobotomies per capita than any other country in the world.

A look at the brain like you’ve never seen it before

03:08

– Source:

CNN

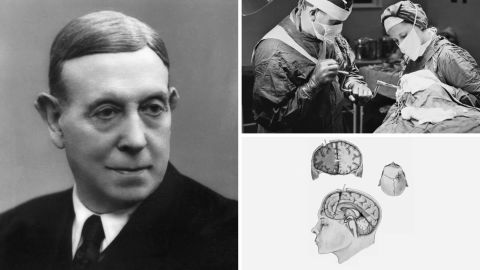

“It’s a very poor treatment, because you destroy a big part of the brain,” Wirenfeldt Nielsen said. “And it’s very risky, because you can kill the patient, basically – but they had nothing else to do.”

Treatment options were limited, and in many ways extreme. Seizures were induced by placing electrodes on either side of the head; insulin shock therapy meant patients were administered large doses of insulin, reducing blood sugar and resulting in a comatose state; and the lobotomy, either transorbital – using a pick-like instrument inserted through the back of the eye to the front lobe – or prefrontal.

The prefrontal lobotomy was pioneered by a Portuguese neurologist, Antonio Egas Moniz. Now considered barbaric, he actually won the Nobel Prize for the procedure in 1949.

A tool is inserted into the frontal lobe, scraping away tracts of white matter – the reason behind the “white cut” moniker. “Emotional reactions … are located at least in part in the frontal lobe,” explained Wirenfeldt Nielsen, “so they thought that just by cutting (there), that could sort of calm the patient down.”

In Kirsten’s case, Inger said there were glimpses of “the old Kirsten” before she got the white cut – but after that, she was gone. In 1951, the year after her lobotomy, Kirsten died.

She was just 24 years old.

On a metal table in a small, standalone building on the grounds of Oringe psychiatric hospital, Kirsten’s brain was removed, set into a small plastic bucket, placed in a wooden box, and shipped – by regular mail carrier – to the Institute of Brain Pathology at Risskov, to join the brain collection.

Søgaard saw the metal table, where a white wooden block still sits on one end – where the heads were placed – and upon which small marks are still visible today. This is where the skulls were opened.

Despite the graphic reminders, in reporting out this story both for herself, and for the newspaper, “it was important (for me) to not write a story that was a horror story,” she said, adding it was easy to look back and say, “How could you do that?”

“I don’t think the doctors wanted to do bad. I think they actually wanted to do good. … I think the most ethical thing you can do is to make sure that you know exactly what you can do with these brains. And that’s what they’re doing now. They’re trying to find out, ‘How can they help us?’”

There have been studies using the collection over the years, including a discovery in 1970 of what is now known as familial Danish dementia, and a new study is ongoing, focused on mRNA in the brains, by Danish researcher Betina Elfving.

For the most part, the brains represent untapped, enormous potential. Yet the one in bucket #738 has already done something extraordinary, thanks in large part to Søgaard herself. She worked to break the cycle of stigma surrounding mental health disorders by sharing her most personal, intimate family details with the world.

“(My grandmother) expressed gratitude,” Søgaard said. “She also said, ‘I feel like I’m moving closer to my sister now.’”